Regime Uncertainty and Trump's Trade Machinations

Conservatives rightly criticised the Obama Administration for rewriting rules so frequently and seemingly arbitrarily that businesses were reluctant to make long term investments. As the WSJ editorialized in 2016:

Pfizer CEO Ian Read defends the company’s planned merger in an op-ed nearby, and his larger point about capricious political power helps explain the economic malaise of the last seven years. “If the rules can be changed arbitrarily and applied retroactively, how can any U.S. company engage in the long-term investment planning necessary to compete,” Mr. Read writes. “The new ‘rules’ show that there are no set rules. Political dogma is the only rule.”

He’s right, as every CEO we know will admit privately. This politicization has spread across most of the economy during the Obama years, as regulators rewrite longstanding interpretations of longstanding laws in order to achieve the policy goals they can’t or won’t negotiate with Congress. Telecoms, consumer finance, for-profit education, carbon energy, auto lending, auto-fuel economy, truck emissions, home mortgages, health care and so much more.

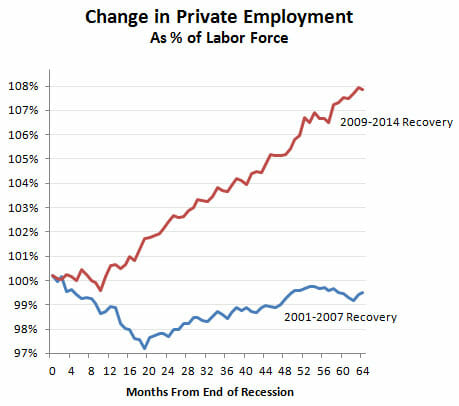

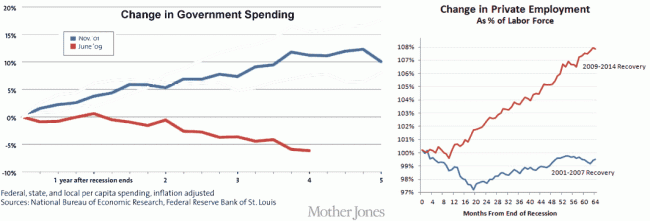

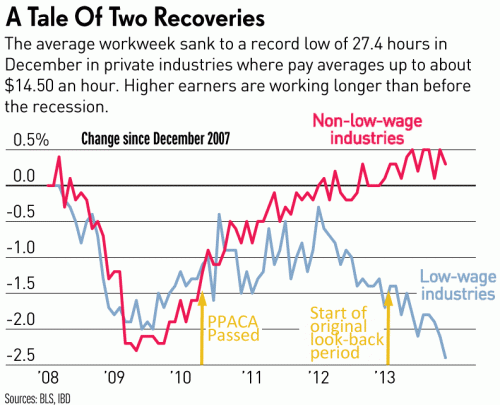

Capital investment in this recovery has been disappointingly low, and one major reason is political intrusion into every corner of business decision-making. To adapt Mr. Read, the only rule is that the rules are whatever the Obama Administration wants them to be. The results have been slow growth, small wage gains, and a growing sense that there is no legal restraint on the political class.

I am willing to believe this is true. On my own smaller scale, our company has disinvested in California because we simply cannot keep up with the changing rules there.

But all this forces me to ask, why doesn't this same Conservative criticism apply to Trump's trade policy? The rules are changing literally by the day -- Consumers of goods from Mexico are going to be hit by new tariffs, Mexican goods are not going to be hit by new tariffs, China is hit by new tariffs, a China deal is near, a China deal is not near, Company A got a special tariff exemption, Company B did not get a special exemption, etc. How can any company with a global supply chain, which is most any US manufacturer nowadays, plan for new products or investments in this environment when they have no ability to make long-term plans for their supply chain?