Is It Science Denial.... Or Authority Denial?

In an otherwise moderately engaging NY Times article about the dual lives (Physicist and Rock Star) of Brian Cox, the author drops in this sentence as a universal truth:

In an era when science denial and disinformation are common...

The increasingly common elite/Leftist charge of science denial really aggravates me. At best, it is a modern elitist virtue signaling tic, thrown into text in the same way a Catholic might genuflect. At its worst, it is used as a totalitarian cudgel to attempt to silence differing scientific and/or political opinions.

Certainly flat earthers, 9/11 truthers, and moon landing deniers exist and have always existed. It took a long time in the 19th and 20th century for average Americans to swallow Darwin, and almost as long for even hard-core geologists in the 20th century to accept plate tectonics. But my contention is that most of the current behavior that elicits cries of science denialism are in fact skeptical not of science itself but of the authorities in academia and government who attempt to mandate scientific truth by fiat and who use the mantle of science to enhance their power. In many cases that skepticism runs too far, for example following RFK Jr over his autism cliff, but this metastasizing of distrust began not with luddite tendencies of the hoi polloi but with the shameful actions of the "elite."

It is impossible to discuss this topic without digging into the government reactions to COVID19, but even before March of 2020 the government and academia where working hard to undermine their own creditability on scientific topics. For example,

- Anyone as old as I will have seen over the decades at least five different, often contradictory sets of government nutrition guidance. And I have never met anyone who makes a living or serious hobby out of nutrition who agrees with any of these.

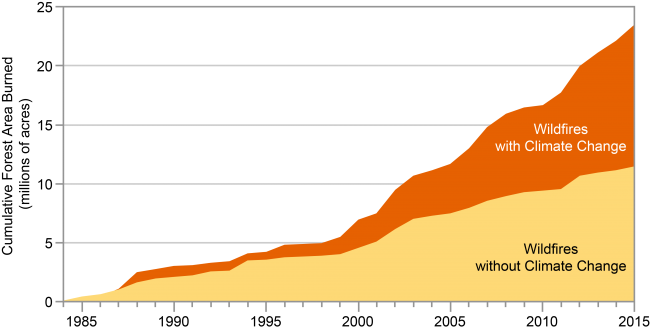

- Without delving into the details of the climate debate, many thinking people are turned off by the catastrophic one-upmanship and overt partisanship of what should be sober scientific researchers and the absurd certainty in ascribing individual weather events to small changes in a chaotic climate system.

- Even before 2020, academia had a severe replication crisis, where university press releases exaggerate actual study findings and where even those more modest results frequently fail to be replicated by other researchers.

But all of this was just a warmup act for COVID, when government officials and leading academics gave Americans every reason to distrust what they say about science. What we have seen is not a backlash against science per se, it is a backlash against authority and the authorities who tried to use the goodwill created by the scientific revolution to protect their power and shield their blundering actions from criticism. Sometimes this skepticism manifests itself in unproductive ways (e.g. avoiding measles vaccines) -- but this skepticism was 100% created by the authoritarian and dishonest behaviors of government officials and academics under COVID. For example:

- Authorities enforced actions, particularly masking and quarantines, that were the exact opposite of what had been recommended by the vast majority of scientific study prior to the pandemic. It is interesting to hypothesize why they might have done this (I have put my hypothesis in the postscript below) but the most meta studies of these topics came to the conclusion that masking and quarantines were net counter-productive.

- Authorities made up rules such as the 6-foot distancing rule that they later admitted were utterly without basis but which at the time they insisted was "science".

- When they came under fire for some of their rules, authorities worked with academics to quickly generate some of the worst-structured studies in medical history to "prove" they were right

- It is increasingly clear that authorities covered up the likely origins of COVID19 as an accidental leak from gain-of-function research at the Wuhan lab. In the process, many social media accounts were suppressed for even suggesting what turned out to be the likely correct origins. The fact that Dr Fauci appears to have been covering up the fact the he signed off on much of the funding, laundered through the EcoHealth Alliance, the resulted in the development of COVID19 makes the story even uglier.

- State and local governments suppressed certain hypothesized treatments (e.g. chloroquine) before any real work could be done to evaluate them merely because other politicians they did not like (ie Donald Trump) seemed enthusiastic about them. I am not sure these treatments ever would turn out to have merit, but in a fast-moving pandemic it is insane to cut off treatment avenues without evidence

- In perhaps the most damaging failure of them all, the efficacy of the rapidly-developed vaccines was greatly overstated while side effects data (which I still believe were small and limited in number) were suppressed. The COVID vaccines were sold as if they were more like polio vaccines (99% effectiveness) when in fact they were more like flu shots (40-55%). In many cases they still allowed transmission and infection but acted as a palliative before-the-fact, reducing severity and greatly reducing risk of death particularly in older patients. Inevitably, people noticed that the shots did less than promised. My belief is that this undermined faith in all vaccines. If you put Mariah Carey's movie Glitter in a top 10 all-time movie list, once people watch it they are going to lose faith in the rest of the list even if every other choice is solid. At the same time, a lot of the potential data on vaccine side-effects was being suppressed. The stated reason was that officials feared that if people saw data that there were bad reactions, however few, they would hesitate to take the shot. This is typical government thinking that flies in the face of reality. Everyone heard anecdotes of people getting side effects, so the side effects were no secret. With the data suppressed, some jumped to the conclusion that there must be something scandalous lurking in the numbers and there was no transparent data source that demonstrated how common or uncommon the anecdotal bad reactions were.

When I have said these things in the past, people have responded that "well, what we understood about the virus was altering day by day -- it is not unreasonable to expect mistakes to be made." Yes, and a hard no. Yes, it was perfectly reasonable to think that as knowledge grew, understanding might change. But no, this is zero excuse for the behaviors displayed by authorities during COVID. There was no modesty at all -- every one of their pronouncements and diktats were issued with smug certainty. People who disagreed were silenced and punished. And over time, nothing changed from authorities as we learned more. As governments do all the time, once they took a position they never moved off of it no matter what the evidence. The same people who insisted that the virus came from those wacky Chinese eating bats still insist the same thing today. It is December of 2025 and I still have a operating contract with LA County that requires all of our employees to be vaccinated against COVID every 6 months.

A few parting thoughts:

- "Science" is not whatever a government official with a science-adjacent job title says it is. For any given area of study, most honest individual scientists will tell you that even they are not sure what the science "says". Scientific knowledge comes only after an initial hypothesis has been replicated or pummeled many many times. There is no gatekeeper that declares when it is settled and if there were such a gatekeeper it sure as hell should not be the government

- Of late the charge of "science denial" tends to be a one-way political attack from the Left aimed at the Right (or at least the not-Left). But most of the folks issuing this attack have their own set of beliefs that fly in the face of the mass of academic research. Whether concerning the effect of minimum wage laws on employment or proper treatment of juvenile gender confusion, the Left is just as likely as RFK Jr -- with his vaccine autism fears -- to latch onto niche outlier studies that support their political preferences. There is nothing necessarily wrong with being an outlier against the masses on the other side of a scientific issue -- most scientists who are famous enough that you know their names are famous because they did exactly this -- but you need to understand you are an outlier and be able to explain why that position is compelling for reasons beyond political convenience.

- Modesty and skepticism are always required when discussing scientific findings. Science not infrequently goes down blind alleys, with years-long adherence to concepts like phlogiston and Lamarckian evolution and decades-long fights for acceptance of theories we now hold dear like plate tectonics or a comet killing the dinosaurs.

- The government funds a lot of science, and while this seems like a better way to spend money than a lot of the other BS that gets funded, it is not without its dangers. Funding can easily get politicized. For example, breast cancer for years received way more money per cancer death than the other top deadly cancers because it was a way for politicians to show solidarity with women's groups. AIDs research was grossly underfunded in early years because Conservatives thought gay sex was icky. Current protests against RFK's changing research grant priorities simply prove my point -- if masses of funding can shift priority based on one guy getting a new job, then putting all our research eggs into the government basket makes no sense.

- A much better way to respond to someone you think is way off base scientifically is not to call that person a science denier but to ask a simple question, "what's your evidence?" For years when I was more active in the climate debate, I got called a climate denier (to which I would always snarkily answer that I do not deny there is a climate). But to my statement that I thought the negative impacts of CO2 emissions were overstated, if I was asked "what's your evidence" I guarantee I could begin a thoughtful discussion. As the holder of a heterogenous opinion on this scientific topic I knew I needed to be prepared to state my case and my evidence.

Postscript -- Why did Fauci and Company go all in for masks and lockdowns when all the prior scientific work and planning advised against them?

This is actually a question I seldom see discussed. Critics of Fauci will simply say he was a bad person, but that is seldom a good explanation. It will come as little surprise to folks who have read my work in the past that I believe we can understand this question by analyzing incentives.

The body of public health research prior to 2020, on balance, held that public masking (and large scale lockdowns, btw) were not effective and generally not recommended (at least once the outbreak is past a very small group). But within weeks of the start of the pandemic in 2020, government agencies like the CDC threw out all this history and decided to mandate masks. Masks were mandated for people outdoors, even when we knew from the start that transmission risks outdoors were nil. Officials even mandated masks for children, who have lower death rates from COVID than the flu and despite a lot of clear research about the importance of facial expressions in childhood development and socialization. So why?

Incentives of the CDC

One needs to remember that the officials of government agencies like the CDC are not active scientists, they are government bureaucrats. They may have had a degree in science at one time and still receive some scientific journals, but so do I. Dr. Fauci has seen about the same number of patients over the last 40 years as Dr. Biden. These are government officials that think like government officials and have the incentives of government officials. They have climbed the ladder to the top of a government agency not by doing brilliant research work but by winning a hundred small and large political knife-fights.

I will take the CDC as an example but the following could apply to any related agency. Remember that the CDC has been around for decades, consuming billions of dollars of years of tax money. And as far as the average American is concerned, the CDC has never done much (at least visibly) in their lifetimes as we never have had any sort of public health emergency when the CDC had to roll into action in an emergency (AIDS might be an exception but it was a much slower-burning pandemic and the CDC did not cover themselves in glory with that one anyway).

If you think this unfair, consider that the CDC itself has recognized this problem. For years they have been trying to expand their mandate to things like gun control and racism, trying to argue that these constitute public health emergencies and thus require their active participation. The CDC has for years been actively looking for a publicly-visible role (as opposed to research coordination and planning and preparation and such) that would increase their recognition, prestige, and budget.

So that is the backdrop -- an agency trying to defend and expand its relevance. And boom - finally! - there is a public health emergency where the CDC can roll into action. They see this new and potentially scary respiratory virus, they check their plans on the shelf, and those plans basically say -- there is nothing much to be done, at least in the near term. Ugh! How are we going to justify our existence? Tellingly, by the way, these agencies and folks like Fauci did follow a lot of the prior science in the opening weeks -- for example they discouraged mask wearing. Later Fauci justified his flip flop by claiming he meant the statement as a way to protect mask supply for health care workers, but I actually think that was a lie. His initial statements on masks were correct, but government agencies decided they did not like the signal of impotence this was sending.

There was actually plenty these agencies should have been doing, but none of those things looked like immediate things to make the public feel safer. Agencies should have been:

- Trying to catalog COVID behavior and characteristics

- Developing tests

- Identifying and testing treatment protocols

- Slashing regulations vis a vis tests and other treatments so they could be approved faster

- Developing a vaccine

If we score these things, #1 was sort of done though with a lot of exaggerated messaging (ie they communicated a lot of stuff that was mostly BS, like long covid or heart risk to young athletes). #2 the CDC and FDA totally screwed up. #3 barely happened, with promising treatments politicized and ignored. #4 totally did not happen, no one even tried. #5 went fabulously, but was an executive project met with mostly skepticism from agencies like the CDC.

Instead, the CDC and other agencies decided they had to do something that seemed like it was immediately affecting safety, so it reversed both years of research and several weeks of their own messaging and came down hard for masks and lockdowns. And, given the nature of government incentives, they had to stick with it right up to today, because an admission today that these NPI aren't needed risks having all their activity in 2020 questioned. And besides, Fauci got himself sanctified and received multi-million dollar awards for insisting on masks and quarantines (and being seen as a foil to Trump), so why would he possibly reconsider?

Incentives for Government Officials Elsewhere

Pretty much all of the above also applies to the incentives of state and local government officials. Our elected officials of both parties have been working to have the average American think of them as super-dad. Got a problem? Don't spend too much time trying to solve it yourself because it's the government's job to do so. Against this background, the option to do nothing, at least nothing with immediate and dramatic apparent potency, did not exist. We have to do "something."

It might have been possible for some officials to resist this temptation of action for action's sake, except for a second incentive. Once one prominent official required masks and lockdowns, the media began creating pressure on all other government officials. New York has locked down, why haven't you? Does New York care more than you? We had a cascade, where each official who adopted these NPI added to the pressure on all the others to do so. Further, as this NPI became the standard government intervention, the media began to blame deaths in states with fewer interventions on that state's leaders. Florida had far fewer COVID deaths, particularly given their age demographics, than New York but for the media the NY leaders were angels and the Florida ones were butchers. For a brief time terrible rushed "studies" were created to prove that these interventions were working, generally by the dishonest tactic of cherry-picking a state with NPI mandates that was not in its seasonal disease peak and comparing it to another state without NPI mandates that was in the heart of its seasonal peak.

And then the whole thing got polarized around party affiliation and any last vestige of scientific thinking got thrown to the curb. Take Chloroquine as a possible treatment protocol. Personally, I have not seen much evidence in its favor but early last year we did not know yet one way or another and there were some reasons to think it might be promising. And then Donald Trump mentioned it. After that we had the spectacle of the Michigan Governor banning this treatment absolutely without evidence solely because Trump had touted it on pretty limited evidence. What a freaking mess. In addition to giving us all a really beautiful view of the hypocrisy of politicians, it also added another great lie to the standard list. To "The check is in the mail" and "I will respect you in the morning" is now added "We are following the science."

Incentives for the Public

I won't dwell on this too long, but one thing COVID has made clear to me is that a LOT of people are looking for the world to provide them with drama and meaning. The degree to which many folks (mostly all well-off white professionals and their families) seem to have enthusiastically embraced COVID restrictions and been reluctant to give them up has just been an amazing eye-opener for me. Maybe I am crazy, but I get the sense that a lot of folks of a certain age miss the COVID days.