Is the World Trade System "Unfair?" -- A Response to the Trump Tariffs

The defenders of the Trump tariffs are starting to coalesce on a few different arguments, but what all these arguments seem to have in common is a core assumption that the current world trade system is "unfair." From Victor Davis Hanson via Powerline:

Our trading partners have taken advantage of us for decades after tariffs were no longer needed to help them rebuild their economies after WWII.

Or this:

I could write a book on this, and many people have, but what follows is my reaction to these tariffs and in particular to the notion that our trading partners are being "unfair."

Yes, many other countries have trade practices that are unfair -- unfair to their own citizens! I went to business school in the late 1980's and at the time it was all the rage a) to bash Japan for "cheating" the US and running a trade surplus and b) to wish to emulate Japan and their MITI-style economic management. I disagreed. I was fairly sure that MITI's control of capital flows was causing unseen distortions that would hurt the Japanese economy in the long-term (I had read my Hayek). At the same time, the Japanese were screwing their own consumers who had to pay far more than Americans for food and most manufactured goods, with far less choice and availability. It was not long after that Japan entered 20 years of stagnation as its trade subsidies and economic distortions just served to nuke their own economy.

Later, about 10-15 years ago, our Chinese exchange student and her friends came to the US for the first time. These kids, as it so happened, live only a few miles from one of the Apple assembly plants. They all brought huge empty suitcases to buy things in the US, including what seemed like a score of iPhones for their friends. The iPhones were far cheaper here in the US than in China where they are made and where many of the other things they bought were not available in China at all. So who is China's trade policy being unfair to? Me, or their own citizens?

I love foreign-subsidized trade. Nothing confuses me more than when people complain about foreign subsidies of exports to the US. Why? If the taxpayers and consumers of Germany wish to subsidize cheaper products in the US market, we should absolutely let them. I mean, I would be pissed off if I were a German citizen, paying higher prices and taxes so a few wealthy manufacturers can meet their quarterly profit goals, but why a US consumer should be unhappy is beyond me. (**see Panda Blog column in the postscript). And remember, we are not just talking about cars and vacuum cleaners, but raw materials and intermediate products bought by US manufacturers and support our domestic manufacturing.

Just as I was about to hit publish on this article, I saw this from Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick defending tariffs:

He further urged, “these people have all been living in our house. They have been driving our car. They come by and visit, open our fridge and eat our food whenever they want.”

“They have taken advantage of us,” he emphasised [sic].

I am sure he will have all the hard-core MAGA types nodding sagely but what the hell does this really mean? In part this is the kind of confusion that results from aggregating what are in fact discrete transactions. Everything Americans buy we pay the asking price for, and everything the Chinese buy they pay our asking price for. How is someone getting cheated? How is there any fraud? Lutnick if pressed would obviously argue that fraud comes from the prices we are paying to the Chinese being artificially low. If that is the case, who is eating out of whose fridge? If I pay $20 less for shoes and $200 less for a phone and that difference is being subsidized by the Chinese people/government, then it is I that is getting over on them. Thanks for the free lunch, China. (update: Even Dave Chappelle agrees)

Hate me if you wish, but compared to consumers, manufacturers are a special interest. 13 million people or so are employed in US manufacturing firms, out of a total workforce of about 160 million, or something like 8%. And by no means are these all in jobs vulnerable to foreign competition -- in fact I would bet at least as many work for companies that are dependent on foreign raw materials for success as there are those working for companies that live at knife-edge vulnerability to competition.

Let me give you an example of a domestic industry entirely vulnerable to foreign competition that tariffs entirely support: Sugar. The US sugar industry would likely disappear if not for tariff's and import restrictions that raise the US sugar price to more than double the world price. We simply do not have the climate or land costs or labor costs to support competitive growing and manufacture of sugar in this country. As a result of tariffs, 300+ million Americans pay more than double for sugar, and perhaps worse, because of the high cost of sugar, food manufacturers in this country have largely abandoned sugar in favor of alternatives like HFCS that are far less healthy. And in exchange for this cost? We are protecting about 12,000 direct jobs. For nearly every tariff in every industry, you will find -- at its heart -- this sort of special interest math.

The history of sacrificing the mass of consumers to the profitability of a few elite producers goes all the way back to the horrible British corn laws. Economists refer to the problem as "concentrated benefits, dispersed costs." Costs are dispersed such that no one person bearing them really has the financial incentive to take on the costs of fighting them, while benefits are concentrated in a few hands that have the incentive and the means to fight to the death to protect their special privilege.

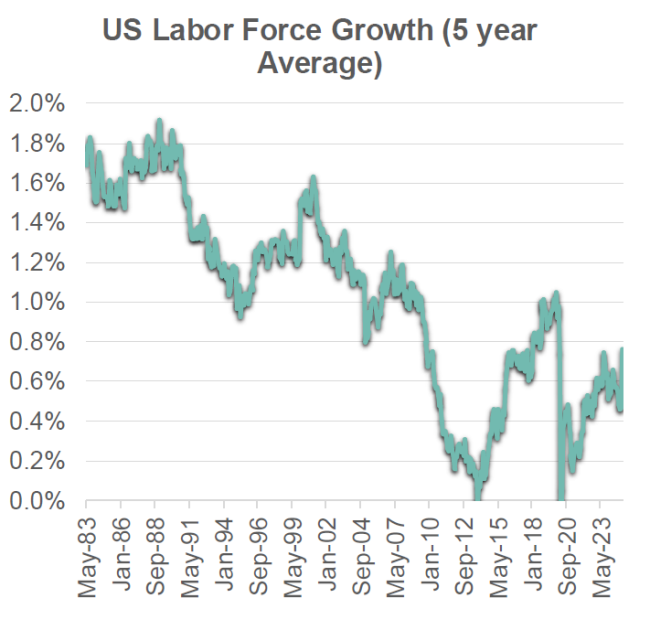

By the way, who is going to work in all these new on-shored manufacturing plants? Due to falling birth rates, the US labor force has been growing only very slowly:

This actually understates the problem, because there is a huge shortage of labor with the right skills for manufacturing. With the US near full employment (though with a relatively low workforce participation), its not clear how we will staff these theoretical new factories. Manufacturers are already screaming they can't get the people they need in the US:

“BlueForge Alliance calls me and they say, we need to hire some tradespeople, and we were wondering if you and your foundation could help.” “I said, I’ll try, as you probably learned, it’s pretty skinny out there … how many do you need?” “They said 100,000.” “100,000 tradespeople for one industry that most people don’t even think about.” “They said, we’ve looked everywhere … do you know where they are?” “I said, yeah I do, they’re in the eighth grade.” “That’s 100,000 building submarines. There’s 80,000 in the automotive industry alone for technicians. Right now … 80,000 openings.” “You start to go down the list and you begin to realize our workforce is wildly out of balance.”

Historically we have had two answers for this problem: 1) more immigration and 2) taking advantage of foreign labor through imports. This administration is trying to cut off both. (Long term there is an education opportunity, that will be addressed below).

If this foreign interventionist trade strategy is superior, why is the US doing so much better? The economies of most major trading nations are all on their back -- except the US. The US is doing very well and still is richer than most any other large nation. Countries like Germany and France that are supposedly so smart to be "cheating" in trade are clearly not doing a very good job of it, because every nation in the EU would be poorer on a GDP per capital basis than the poorest US state (Mississippi). Great Britain through most of the 20th century ran their economy into the ground through protectionism, leaving their industry bloated and inefficient. The US did the exact same thing in its auto and steel industries until tariffs were lifted in the 1970s. We have a smaller auto industry than we did then, but it is healthier and makes FAR better products.

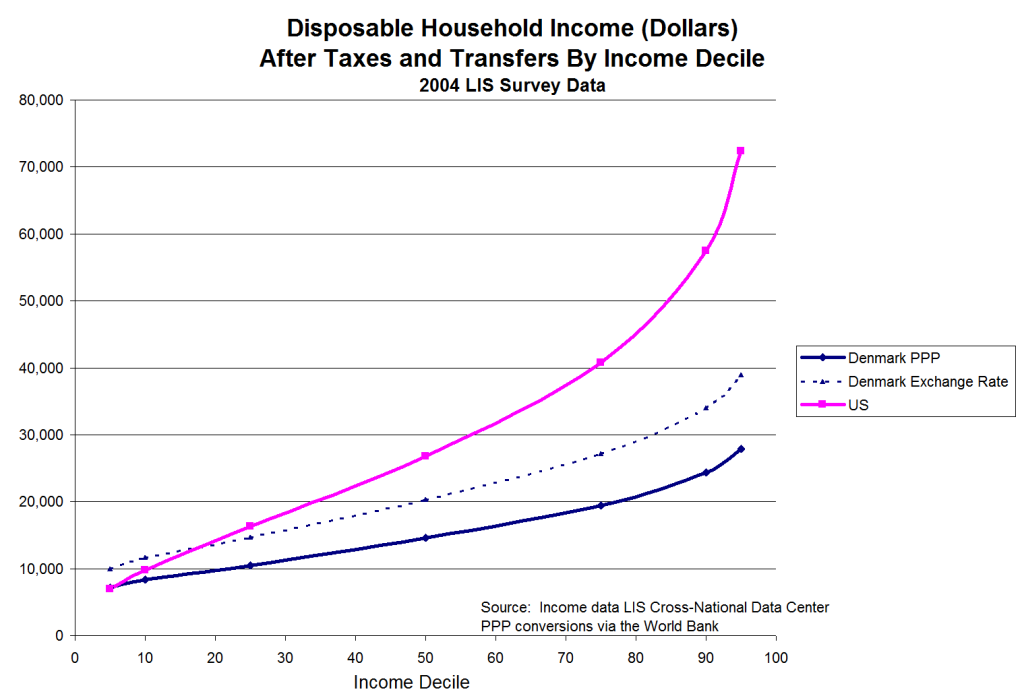

The US is wealthier across the whole of the income spectrum than, say, countries in the EU. Our rich are richer than their rich and our middle class is richer than their middle class and our poor are better of than their poor, even considering the net of taxes and transfers. I have not updated this analysis for over a decade but I am pretty sure it is still directionally accurate.

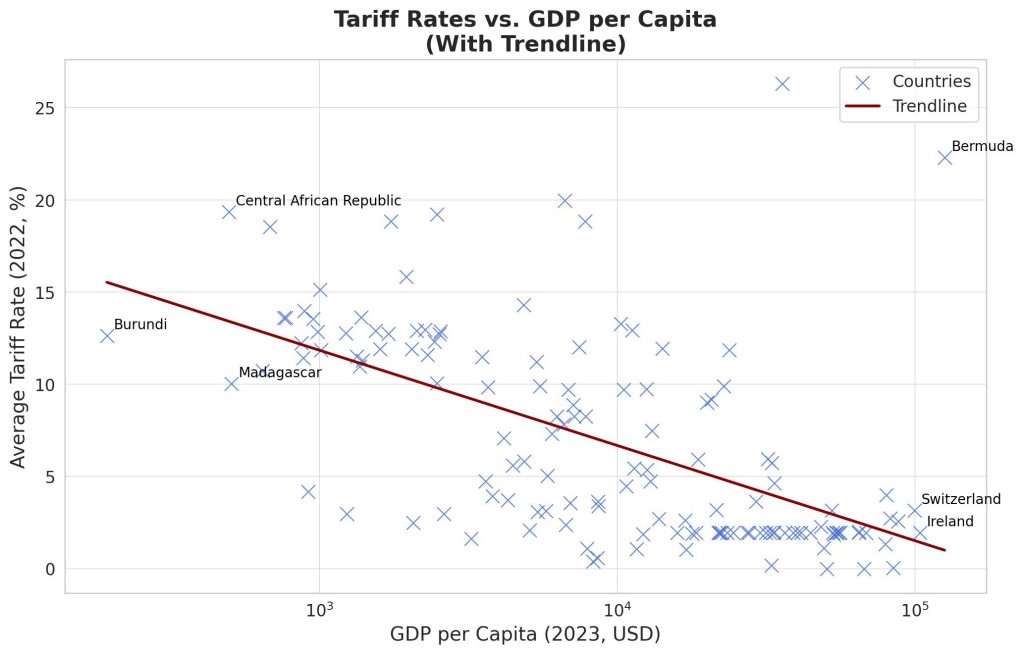

In fact, there is a fairly direct correlation between low tariffs and citizen well-being:

I don't know where the average South Korean's or Thai's head is at on all of this, but I can say with some confidence that the average Western European citizen would be shocked at the notion that a) their country is somehow beating up on the United States and b) that they personally are getting rich at the expense of American citizens.

It should be noted that even when all else is equal, the fact that US citizens are substantially wealthier than their peers in other nations, it is almost mathematically guaranteed that we will buy more (ie import) than we sell in return in exports.

The Shifting of Jobs Out of Manufacturing Is A Normal Part of Economic Growth. Certainly a smaller percentage of Americans work in factories today than they did 30 or 40 years ago (ignore the Trump stat about 90,000 factories disappearing, though, it is totally fake). You know what other industry has lost jobs through US history? Agriculture. Today about 2% of the population works in farming vs well over 80% in the year 1800. I am pretty sure few today are pining away for a return to the life in a small farm -- I guarantee farmers and ranchers work way harder than most folks want to work today.

As the economy gets wealthier and technology advances, the nature of work keeps shifting. We are upgrading lower-skill, lower-productivity jobs for higher productivity jobs, just as we have since the start of the industrial and agricultural revolutions. We still need the things made in those lower skill, lower productivity jobs, so they shift to other countries (which in turn helps them get wealthier too). No one is demanding we shift workers back from manufacturing to agriculture, and no one should be arguing that we shift folks working on AI back to manufacturing.

Of course this process can have costs for individuals and communities. But we almost never wish to turn back the clock on past such transitions while still greatly wishing to block the current one.

These tariffs are not strategic. I have seen the most enthusiastic of Trump supporters try to argue that this is really about returning certain manufacturing to the US for strategic reasons. But this can't possibly be correct, or if it is, then its a really odd approach since these tariffs apply to every single country and every single product.

This may yet be another Trump negotiating ploy, but its a really expensive and high risk one. Trump supporters who have more than half a brain like Victor Davis Hanson are arguing this is just Trump putting a negotiating token out there. Perhaps. That is certainly Trump's style, to make an irrational demand and soften it only when he gets something back. Secretary Lutnick explicitly says this is the plan, and I will believe him. This is obviously expensive and high-risk, and to some extent still doesn't make a lot of sense since Trump slapped high tariffs on countries like Switzerland that have close to zero tariffs themselves and are largely productive partners.

It may well turn out that much of this ends up being performative. I need to remind everyone of Trump's much ballyhooed deal to get Foxconn to commit to a $10 billion plant in Wisconsin. I don't know if Foxconn ever intended to follow through, but in the end they never made most of this investment and the whole effort turned out to be performative. One interesting aspect of this article is that Foxconn backing out was not the only problem, there was a lot of local opposition as well for a variety of environmental, land use, and public policy reasons. It illustrates that the manufacturing labor shortage discussed above may not be the only reason manufacturing is shrinking in the US.

Trump supporters need to admit there is some vanity here. Trump likes to have people come to him hat in hand as a supplicant -- to kiss the ring, to thank him, to apologize, whatever. He blasted Zelenskyy for not doing just this on his White House visit (though I will confess I find Zelenskyy to be immature, irritating, and possibly corrupt). Trump supporters will say that what he really wants is for countries to show respect for America, and I suppose this is part of it, but I am convinced ego is a part of it as well.

There is more risk here than just price increases. Consumers are going to lose choices and many of those choices are going to be the low-cost options. Already Mercedes has hinted it may stop selling its entry level cars in the US. And yes, I know it is hard to cry for the Mercedes buyer, but the same math that causes the tariffs to hit hardest at their entry-level products (as they tend to have the lowest margins and the highest customer price sensitivity) is going to apply to about every other consumer product.

Ironically, one huge risk is to manufacturing investment. Trump's goal seems mainly to get more manufacturing investment in the US, but as long as the tariffs keep changing week to week -- and they will continue to if Trump is really using them as a bargaining chip -- no manufacturer in their right mind is going to make a major new investment. They are going to sit on their hands and wait. Many historians and economists of late have been coalescing around a theory that regime uncertainty in the 1930s -- ie the constant changing of regulatory rules and frameworks -- did much to cause the Great Depression to drag out longer.

And then there is the risk of cronyism. A system of high tariffs gives a huge new playing field for politicians to trade favors with favored companies, giving them special exemptions or hitting their competitors with extra costs. If you look at European politics around tariffs, it is a relatively ugly picture of favoritism to a few select elite. I guarantee you the special favors for Nike and Apple are already being discussed in the back rooms. Just look at the Foxconn deal discussed above, where Trump and WI governor Walker bought a trade-related election talking point for $4.5 billion in subsidies.

Update: And of course there is the threat to the rule of law. I left this out on the first draft because, frankly, I don't think the faithful of either party gives a sh*t about the rule of law if it is their agenda hat is being rammed through. Certainly Democrats didn't have any problem with Biden's lawless attempts to forgive a trillion dollars in student loans and I don't think Trump's supporters care about the legality of this tariff actions. The power to set tariff's is enshrined in the Constitution (that document Republicans used to care about) as a power of Congress. Weak-kneed and lazy Congresses have delegated some of this power to President's, but only very narrowly. The picture is complicated and illegal actions by the President can be hard to review in court. But looking at the 4-6 major delegations to the President of tariff authority, it is difficult to see that any of them apply simultaneously to every country on Earth and every single product manufactured anywhere. Certainly there is no precedent for them being enacted by the President on anything but a far far narrower basis (eg steel from China).

I also left out the issue of honorable dealings, which again I don't think political partisans of any flavor give a crap about. But Trump is violating any number of agreements, including not just lame President-only agreements like much of the climate stuff but real treaties that were legally passed by the Senate. He is also explicitly repudiating deals he personally made with Mexico, Canada, and the EU, among others. I suppose it is fine for him to behave this way in his personal negotiations for his personal businesses -- it is only his honor involved. But there is a real cost involved to the honor and reputation of the nation which makes it harder in the future for such agreements to be made.

So let me end by offering a few alternatives to tariffs to achieve some of Trump's stated goals.

Alternative 1: If you really want to reduce trade deficits, cut the government budget deficit. As I said above, the US is likely always going to run trade deficits as long as it is wealthier than the rest of the world. But probably the #1 thing that has caused these deficits to be higher than they would otherwise be is the huge Federal debt. Every year now we are issuing trillions of dollars of new US Federal debt. This pushes the interest rate for these bonds higher than the #1 risk-free world investment might otherwise be. This in turn attracts foreign capital, which buys dollars in order to buy of these bonds, which in turn increases the value of the dollar. This artificial inflation of the value of the dollar certainly helps consumers, by reducing the cost of imported goods, but hurts exporters by increasing the cost of their goods in local currencies of buying nations. The net effect is that government borrowing increases the trade deficit. Close the budget hole, and the trade deficit will come down over time.

Alternative 2: If you really want to increase US manufacturing, you need to increase the number of workers with trade skills. We talked above that US manufacturing is already limited by the lack of workers in skilled trades. In part this is due to government programs that pay people just enough that they play Call of Duty all day and still eat. But it is also due to the great fuck-up of our educational system. Public education has become complete crap. But even worse for manufacturing is the fact that we have for thirty years promoted a value system where it is high status to go to college and get a degree in the Lesbian poetry of Peru while it is low status to get a trade and go to work in manufacturing. The economic signals are pretty good -- the Lesbian poetry grad is probably unemployable while my friend with no college degree but welding skills makes 6 figures at SpaceX. But for some reason we have an entire hierarchy in education that says its wrong to encourage kids into trade schools -- they need to go to college. Starting to fix this is beyond the scope of this post but far more essential to US manufacturing than tariffs are.

**Postscript: I will conclude by recognizing that none of the above is recently adopted out of TDS, which I don't have. I would love certain parts of Trump's agenda to be succesful. But I have been making these same points for 20 years. Below is a post I wrote for my imaginary Chinese affiliate "Panda Blog" from an imagined Chinese citizen in 2006:

Our Chinese government continues to pursue a policy of export promotion, patting itself on the back for its trade surplus in manufactured goods with the United States. The Chinese government does so through a number of avenues, including:

- Limiting yuan convertibility, and keeping the yuan's value artificially low

- Imposing strict capital controls that limit dollar reinvestment to low-yield securities like US government T-bills

- Selling exports below cost and well below domestic prices (what the Americans call "dumping") and subsidizing products for export

It is important to note that each and every one of these government interventions subsidizes US citizens and consumers at the expense of Chinese citizens and consumers. A low yuan makes Chinese products cheap for Americans but makes imports relatively dear for Chinese. So-called "dumping" represents an even clearer direct subsidy of American consumers over their Chinese counterparts. And limiting foreign exchange re-investments to low-yield government bonds has acted as a direct subsidy of American taxpayers and the American government, saddling China with extraordinarily low yields on our nearly $1 trillion in foreign exchange. Every single step China takes to promote exports is in effect a subsidy of American consumers by Chinese citizens.

This policy of raping the domestic market in pursuit of exports and trade surpluses was one that Japan followed in the seventies and eighties. It sacrificed its own consumers, protecting local producers in the domestic market while subsidizing exports. Japanese consumers had to live with some of the highest prices in the world, so that Americans could get some of the lowest prices on those same goods. Japanese customers endured limited product choices and a horrendously outdated retail sector that were all protected by government regulation, all in the name of creating trade surpluses. And surpluses they did create. Japan achieved massive trade surpluses with the US, and built the largest accumulation of foreign exchange (mostly dollars) in the world. And what did this get them? Fifteen years of recession, from which the country is only now emerging, while the US economy happily continued to grow and create wealth in astonishing proportions, seemingly unaware that is was supposed to have been "defeated" by Japan.

We at Panda Blog believe it is insane for our Chinese government to continue to chase the chimera of ever-growing foreign exchange and trade surpluses. These achieved nothing lasting for Japan and they will achieve nothing for China. In fact, the only thing that amazes us more than China's subsidize-Americans strategy is that the Americans seem to complain about it so much. They complain about their trade deficits, which are nothing more than a reflection of their incredible wealth. They complain about the yuan exchange rate, which is set today to give discounts to Americans and price premiums to Chinese. They complain about China buying their government bonds, which does nothing more than reduce the costs of their Congress's insane deficit spending. They even complain about dumping, which is nothing more than a direct subsidy by China of lower prices for American consumers.

And, incredibly, the Americans complain that it is they that run a security risk with their current trade deficit with China! This claim is so crazy, we at Panda Blog have come to the conclusion that it must be the result of a misdirection campaign by CIA-controlled American media. After all, the fact that China exports more to the US than the US does to China means that by definition, more of China's economic production is dependent on the well-being of the American economy than vice-versa. And, with nearly a trillion dollars in foreign exchange invested heavily in US government bonds, it is China that has the most riding on the continued stability of the American government, rather than the reverse. American commentators invent scenarios where the Chinese could hurt the American economy, which we could, but only at the cost of hurting ourselves worse. Mutual Assured Destruction is alive and well, but today it is not just a feature of nuclear strategy but a fact of the global economy.

I am generally not a fan of tariffs and definitely believes Trumps tariff spasm is bad economic policy.

That being said, the economy has been on a sugar high since circa 2009. Its been reasonable to expect a recession within the next 6-12 months unrelated to the tariff fiasco.

What do you think of Robert Barnes on tariffs. Start at 44 min mark. Tariffs https://rumble.com/v6rqf5l-ep.-258-taibbi-sues-for-defamation-trump-tariff-madness-russell-brand-green.html?e9s=src_v1_ep

Coyote: Nothing confuses me more than when people complain about foreign subsidies of exports to the US. Why? If the taxpayers and consumers of Germany wish to subsidize cheaper products in the US market, we should absolutely let them.

Most of your post is well-thought. However, markets are not completely frictionless. When a foreign country subsidizes an industry, it can be predatory. In other words, subsidies of a foreign industry can be used as a weapon to undermine the domestic industry. As it takes significant investment in time and finance (the friction) to build industrial infrastructure, once the domestic industry goes under, that allows the foreign industry free rein within that sector, even without continuing subsidies. This, even though overall prosperity is inhibited.

Another reason for subsidizing industry is if the foreign supply is unreliable. Political tensions could lead to a cutoff of trade. Or the supplier might have unreliable weather than can lead to agricultural shortages. Or perhaps they have an irrational leader who makes irrational decisions about trade. Could happen.

Zachriel says: "When a foreign country subsidizes an industry, it can be predatory. In other words, subsidies of a foreign industry can be used as a weapon to undermine the domestic industry."

This sounds very much like the old argument against monopolies that sounds good when not digging too much but has never been proven accurate in the real world. Any example of a "country" screwing another one by destroying some industry through dumping?

Best I can think of was the rare earths crisis of ten (?) years ago. Which leads to the topic of reliability of suppliers. Which in my view is none of the government's business but each company's worth its salt...

Coyote: Trump supporters need to admit there is some vanity here. Trump likes to have people come to him hat in hand as a supplicant -- to kiss the ring, to thank him, to apologize, whatever.

Leading to an authoritarian competition of toadying.

Student of Liberty: This sounds very much like the old argument against monopolies that sounds good when not digging too much but has never been proven accurate in the real world.

The oil trusts were very effective at stifling competition. Modern monopolies, such as Microsoft or Google, are usually shorter-lived, but can still have a pernicious effect.

Student of Liberty: Any example of a "country" screwing another one by destroying some industry through dumping?

China is heavily subsidizing green energy industries, including low-cost electric vehicles and solar photovoltaic. Chinese government subsidies are about 2% of GDP, triple or more that of the USA, Germany, or Japan. That allows Americans to buy low-cost solar panels, but at the expense of American manufacturers. WTO rules allow for compensating tariffs.

I agree with a lot of these points, but I take issue with a few:

1."It should be noted that even when all else is equal, the fact that US citizens are substantially wealthier than their peers in other nations, it is almost mathematically guaranteed that we will buy more (ie import) than we sell in return in exports."

That's a fallacy and an illogical use of national account data. The endpoint of this thinking would be to expect countries with <$1,000 GDP per capita to run massive current account surpluses. Which prompts the question: just how would these countries be so low-income while producing so many goods and services that the rest of the world buys?

The answer, as suggested by that thought experiment, is that a higher-income country (the US, in Warren's example) both *produces* and *consumes* more goods and services per capita. So we'd expect it, other things being equal, to account for shares of *both* global exports and global imports that reflect its high GDP.

Warren does touch on the real reasons that the US is likely to run a current account deficit in his point about the US government budget deficit. A current account deficit (net trade in goods and services) is the mirror of a capital account surplus (net investment flows). The budget deficit and private savings rates factor into whether a country is likely to run a capital account surplus, raising money (both borrowing and equity purchases) from abroad.

For the US, though, the dollar's role as a reserve currency and the scale of US financial markets make it likely that we'd run at least some capital account surplus even with a lower government budget deficit. The US is an attractive place to invest capital due to our currency (often used for international trade even between two non-US countries), our large and very liquid equity and bond markets, many large multinational companies trading on our equity markets, lack of strict capital controls, and history of rule of law.

(It's not intuitively obvious how FDI flows - foreign companies directly investing into operations - should be expected to net out for the US. On the one hand, it's clearly attractive for foreign companies to invest in US operations to serve the very large US market. On the other hand, the large domestic market means that the US is the home country of many large companies, who have the scale to invest in foreign countries and operate globally.)

2."And, incredibly, the Americans complain that it is they that run a security risk with their current trade deficit with China! This claim is so crazy"

Has Warren since modified this 2006 "Panda Blog" view? I don't think that US risks of trade with China are precisely because of the "trade deficit", as I'd tie them more broadly to overall level of trade/integration with the Chinese company.

I'm thinking to date of not only China cutting off exports of rare earths, but examples like China going after foreign companies for how they list "Taiwan" on the countries list of a website not even viewable in China, going after a company for a corporate account tweeting a quote from the Dalai Lama, cracking down on the NBA over a Daryl Morey Hong Kong tweet, or hitting Australian exports with a mix of cutoffs and high tariffs after the Australian PM called for an inquiry into COVID's origins.

A CCP-ruled China is a geopolitical rival to the U.S. and allies not only because of specific conflicts such as the Chinese claim to Taiwan, but because the CCP is ideologically opposed to the values of constitutional democracies and respect for individual rights. And the CCP tries to export its own censorship whenever it thinks it can get away with it, using market access, near monopoly on key items in supply chains, and whatever other tools are at its disposal. Whatever the imperfections of platforms like Google and Meta, I feel better about their decision-making knowing that they generate limited revenue from inside China, so their content policies are insulated from CCP browbeating.

In broad terms, I'd accept a bit lower US standard of living as the price of moving supply chains away from China and lessening integration with its economy. What are the risks for freedom of expression and US weapons technology in a hypothetical future world where almost all computer chips come from China? It is worth incurring costs to protect against those risks, analogous (imo) to Cold War defense spending that helped protect allies like Western Europe and Japan from potential Soviet domination.

A big problem with Trump's tariff policies, of course, is that they target the whole world, not just China.

3."The US did the exact same thing in its auto and steel industries until tariffs were lifted in the 1970s. We have a smaller auto industry than we did then, but it is healthier and makes FAR better products."

I don't think autos are a good example. The Big 3 make huge profits - perhaps more than 100% of their total profits from the US market - by selling light trucks, a product category where imports are still subject to the 25% "chicken tax".

And the "voluntary" quotas on Japanese auto imports during the Reagan Administration aren't the only reason for Japanese investments to build assembly plants in the US, but that policy (and the memory of it) is a factor.

In any case, the auto industry is so heavily politicized - in both the US and other countries - that it's tough to attribute specifics to market factors. Holman Jenkins (an opinion columnist at the WSJ) frequently offers an insightful view on the Detroit 3: they get tariff protection to benefit their light truck profits, at the expense of immense political pressure to keep employing expensive UAW labor, as well as additional regulatory mandates (CAFE, EV policy) that saddle those automakers with expensive burdens paid for out of light truck profits.

Zach: "The oil trusts were very effective at stifling competition."

Not nearly so effective as the passed down conventional wisdom believes. Standard Oil's refining market share dropped from 91% in 1904 to 70% in 1906 (when the government brought its antitrust case) to 64% in 1911 (when the antitrust case ended with a judgement to break up Standard Oil). It had 100+ competitors in the refining market when it was broken up. From page 11 at https://www.ntnu.edu/documents/1297014369/1326993163/Case+10+Standard+Oil.pdf/c1fa3e29-ef5a-5618-f8f5-efd50d132aa7?t=1675962993403

Dave T: Not nearly so effective as the passed down conventional wisdom believes.

While the monopoly was not absolute, the article you cited shows how they used unfair monopolistic practices to gain unfair advantages in the marketplace, a finding affirmed by the Supreme Court.

The world trade system is very unfair. Just think of the poor American banana farmers unable to compete with the flood of cheap foreign bananas.

"It should be noted that even when all else is equal, the fact that US citizens are substantially wealthier than their peers in other nations, it is almost mathematically guaranteed that we will buy more (ie import) than we sell in return in exports."

I don't think this is quite right. If it were true, what would the exporting countries do with the dollars they receive?

It fundamentally comes down to a flow of funds issue - funds (money) going one way need to be balanced by some financial asset (maybe money, maybe something else) going the other way. In the immediate aftermath of WWII, the US was a net exporter, and the balancing fund flow was (mainly) investment by US firms in overseas firms or overseas operations. Later, the foreign investment slowed down, and the balancing fund flow was mostly repatriated profits from foreign operations or dividends or loan repayments from foreign firms.

Nowadays, the US, particularly government bonds, is a prime destination for foreign investment. With the US running enormous budget deficits, it has enormous requirements for borrowing - currently around 6% of GDP per year. Much of this comes from foreign sources; the foreign sources have to get the money from someplace, and exports to the US is the main source.

We are facing a debt crisis, or at least a fiscal crunch due to debt. Deficits from 2009 to 2020 were manageable because interest rates were near zero. With interest rates returning to more normal levels, federal interest payments have been increasing rapidly, and are sure to continue. This will put enormous pressure on all parts of the federal budget. Trump's unpredictable behavior is likely already causing foreign investors to re-evaluate their appetite for US government bonds, which will make it harder to borrow, and cause interest rates to increase further.

We're likely to see some ugly combination of much higher taxes, drastic spending cutbacks, and higher inflation. This situation was inevitable, at least since 2009. If Trump and his team were interested in good policy, they might make it less bad, but they're obviously not.

All Trade implies an exchange of values. Usually the calculation of value requires the inclusion of other costs. I chose to outsource my kids education to the State. There were unfortunate consequences that I will have to live with. If the local store advertises anti-semitic causes, I am free to pay more somewhere else. If a country does not observe Intellectual Property, I am faced with a choice: Pay less and support illegal copies or pay more? Do I pay more for locally produced clothing or cheaper foreign goods?