For the Left, Excess Hospital Beds Were "Too Many Deoderants" ... Until This Month

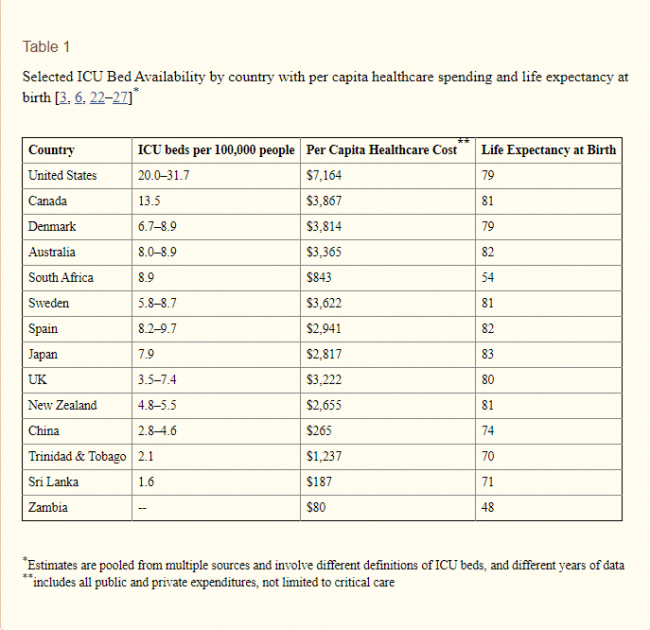

For years, a significant critique (mostly from the Left) of health care costs has been that over-investment by private hospitals in premium facilities (e.g. ICU beds, MRI scanners, etc) is part of the reason health care costs have been rising so rapidly. This is why the response to a study like this from several years ago was not "wow, how fortunate the US has so many ICU beds" but instead "wow, this is what is wrong with US healthcare." This is why per capital healthcare cost is in the next column, implying a link between more beds and higher costs. And, this is why the "life expectancy at birth" is included in the chart. The conclusion was supposed to be "see, the US spends all this money on ICU beds and gets nothing for it." (Obviously this conclusion would be absurdly narrow-minded even before COVID-19, as US life expectancy is lower than that of many other countries due to lifestyle choices and other factors -- a better comparison would be US life expectancy at 65, where US looks much better).

As a result, many states and municipal authorities have Certificate of Need (CON) processes that require hospitals and other health care providers to get government permission before adding certain types of capacity/infrastructure. Many of these government agencies actually delegate these decisions to a board populated with representatives of the current local incumbent hospitals, meaning one must get permission from one's competitors before adding capacity (permission unlikely to be given).

This sort of regulation has had acute consequences in the age of COVID-19. John Phelan has an example from Minnesota.

With the extra time, Minnesota will work desperately to expand its ICU capacity. Local stadiums and hotels will be converted to temporary hospitals. “The attempt here is to strike a proper balance of making sure our economy can function; we protect the most vulnerable; [and] we slow the [infection] rate to buy us time and build out our capacity to deal with this,” Gov. Walz said....

Until 1984, Minnesota operated what were called Certificate of Need (CON) laws. These require government permission before a facility can expand, offer a new service, or purchase certain pieces of equipment. While Minnesota has not operated CON laws since 1984, along with two other states—Arizona and Wisconsin—it maintains several approval processes that function like CON laws.

In 1984, Minnesota enacted a hospital construction moratorium. This prohibits the building of new hospitals as well as “any erection, building, alteration, reconstruction, modernization, improvement, extension, lease or other acquisition by or on behalf of a hospital that increases bed capacity of a hospital.” Whenever hospitals or provider groups propose an exception to the moratorium, the Minnesota Legislature requires the Department of Health to conduct a “public interest review.”

Researcher Patrick Moran explains:

In its review, the Department must consider whether the proposed facility would improve timely access to care or provide new specialized services, the financial impact of the proposed exception on existing hospitals, the impact on the ability of existing hospitals to maintain current staffing levels, the degree to which the facility would provide services to low-income patients, as well as the expressed views of all affected parties. [Emphasis added]

Moran continues:

These reviews must be completed within 90 days of the proposed project. However, the public interest review is not binding. The Minnesota Legislature ultimately decides which exceptions are allowed to go forward. Except for the fact that the Legislature makes the final determination about each project, the public interest review process for new hospitals and hospital beds closely resembles CON statutes in other states. [Emphasis added]

Indeed, it is incredible to note that, as with CON laws, the purpose of this system is to make it harder to provide hospital beds in Minnesota. Moran says: “Policymakers hoped that the moratorium would be more effective than CON in reducing the growth of hospital beds.”

They appear to have been successful. In the twenty years from 1984 through 2004, 16 exceptions were granted permitting just 94 additional licensed beds. As the chart below shows, between 1996 and 2016, the number of licensed beds in Minnesota actually fell by 921 while the population increased by 810,000. Exactly how “the Minnesota Department of Health has concluded that the moratorium is largely ineffective in restraining bed capacity”, as Moran says, is something of mystery.

The reason for this sort of thinking has in part been based on misunderstandings on the Left about markets (similar to Bernie Sanders and his too many deoderants statement). But it is part based on the reality that the US healthcare system is stuck between two different regulatory models.

- In model 1, which we will call free market, investment by private actors increases supply. In such a market with a lot of fixed investment, prices are driven down as competitors vie to fill excess capacity. This is close to the model the US has in veterinary medicine and some non-insurable surgeries like eye correction and plastic surgery, but is far from the model we have in most patient care

- In model 2, which I will call the public utility model, a small number of private companies operate with heavy regulations of services and prices in exchange for a guaranteed return on assets. Since the size of the asset base drives profits, private players have the incentive to add lots of assets while regulators look on asset additions skeptically

The US patient healthcare system is stuck between these models, which may be a worse spot than either alone. Dominance of third party payers or even a single government payer tends to drive the system towards model 2. But model 2 is notoriously bad at producing innovation, often results in poor capital allocation decisions, and sub-optimizes costs compared to model 1.