I got some attention with a post the other day about an example of something I see constantly -- government employees unwilling to admit even the smallest error.

One reason is that even as someone who runs a company that partners with government agencies frequently, I am still an outsider and a member of the general public. And government agencies train everyone in their organizations never to give any information to the public that is not fully vetted and controlled. Government agencies have had their training budgets slashed, but the one training everyone still gets (along with diversity training) is training on how to reveal (or really, not reveal) information to the public.

But I think there is a more important reason for this behavior, and it is one I want to spend a bit of time on in part because it is one of my favorite business topics: incentives. There is nothing in an organization that is harder to get right than incentives. And this is doubly true of government agencies because most government agencies don't have, or don't choose to measure, any output variables.

What do I mean by output variables? Organizations tend to measure both what I call input and output variables. Let's consider a sales person. An output variable is a business result, e.g. number of units sold, number of new customers added, revenue of products or services sold, gross margin of products sold, satisfaction rating from customers. An input variable is a measure of how well process steps leading to that sale were completed, e.g. percent conformance to pricing guidelines, number of sales calls made, number of quotes produced. If well selected, input variables tend to lead to the output variables but they don't in themselves pay the rent.

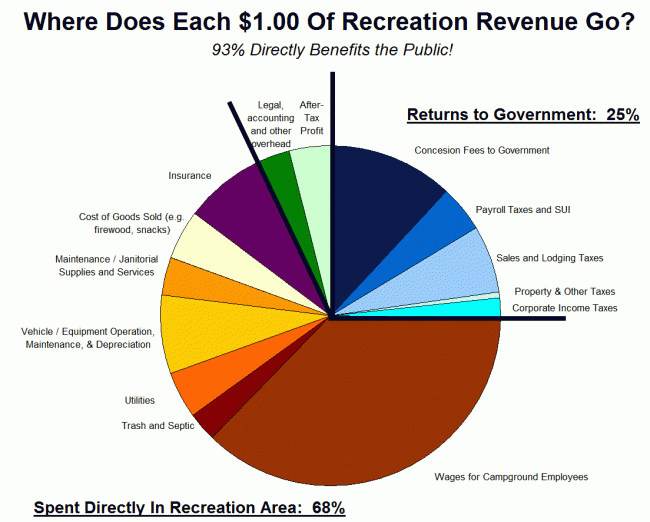

Because I am most familiar with them, I am going to use government recreation agencies like a state parks organization as an example. I have yet to find a government recreation agency that measures its employees primarily on output variables, e.g. customer satisfaction of park visitors, fee revenue collected at park, net income of the park, change in deferred maintenance accounts, etc. Instead their metrics are -- at best -- based on conformance to process, e.g. was the budget completed on time, was the planning process done right, was all necessary reporting done on time, etc. I say "at best" because most government agencies have no formal performance metrics at all. And this is where I get to my favorite incentives / metrics topic of all -- informal performance metrics.

An organization never has no performance metrics at all. They may have no formal, written standards, but every organization has to evaluate and promote talent. If there are no formal standards, there have to be some informal or unwritten standards that are applied. And I would argue from my experience that even when formal standards do exist, there may still be informal standards that are more important.

One informal incentive that exists naturally in almost every organization is "don't get caught in a mistake." On its face this is one of those incentives that seem good -- sure, I would love to have an organization where no one makes mistakes. But many companies have found that in competitive markets, allowing this informal incentive to become powerful can spell a company's doom. It has at least two negative effects: it limits honest communications, because people start hiding their mistakes which in turn keeps information from the rest of the organization that may need it; and it limits risk-taking, which is necessary for most companies to survive in competitive markets, because almost everything a company does to improve contains risks. Powerful formal performance systems are one way to limit counterproductive informal incentives like this. But many companies also put a lot of work into their communications and culture to help employees be more open to taking risks and making mistakes. A vast portion of my communication with my own managers and employees are on this topic. We try to make very clear the subset of mistakes that are career fatal and where we DO want risk aversion (e.g. racism, harassment, abuse, etc) and treat everything else as a learning exercise. My response to one of my manager's mistakes is very likely to be, "sorry, that was my fault, I did a bad job of training you (or preparing you, or whatever) for that issue."

Recognize though that all of these corporate steps to head off problems with the informal incentive "don't get caught making a mistake" have largely been lessons of the marketplace. Time warp back to the 1950's when American companies were fat and happy and not yet really faced with scrappy global competition, and you might well have found highly risk-adverse cultures where people were afraid of being caught in a mistake. I do not have experience at companies like GM, but I would not be surprised at all to learn that risk aversion dominated the culture and that faced with market extinction, it has spent much of the time since the 1970's trying to purge this risk aversion from its culture.

But in large part, a government organization doesn't face these market corrective forces. If an agency becomes weak and senescent, it does not get competed into oblivion, it simply goes on and on. Maybe it gets more tax money to make up for its inefficiency, or maybe it cuts somewhere (such as deferred maintenance in public parks) to make ends meet. Which means that in most government agencies I have worked with, informal incentives -- particularly "don't get caught in a mistake" -- are extremely powerful.

Most people are familiar with the fact that the default government answer to anything new is "No". But did you ever wonder why? I have heard a lot of folks say that it is because government employees are jerks or lazy under-performers or have evil intentions. But that is really not the case. With just a couple of small exceptions**, people who enter government are no different than people who enter private organizations. If they do things that seem bad, it is not because they are bad people but because their information and incentives cause them to do things we perceive as bad. Take the case of saying "No". Without any output metrics, most government employees have no incentive to say "yes". There is no incentive to, say, generate 20% more visitor revenue in parks so there is no incentive to approve new visitor facilities or services that might generate that revenue. And there is every reason so say "no". "No" is almost always safe, particularly if one does not actually say "No" but instead say something like, "well, that is an interesting idea but we need to do X, Y, and Z intensive 20-year studies first." There is virtually no way for any government employee to get caught in a mistake saying that. So that is the answer most of us get from the government.

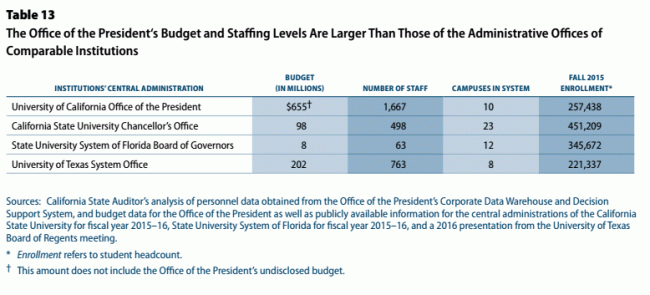

Coming back to the original question, I hope this helps explain why agency employees who don't admit error act the way they do -- they are not bad people, they are normal people reacting to a bad incentive. Imagine in my business if I, say, reversed two numbers on one of the 25 state and local sales tax returns we file each month. When pointed out to me, I have no problem admitting the mistake because I know it is easily correctable and that it has little to do with my true performance. But in the government world, things are completely different. They don't have output variables. Executives can have full successful careers running parks where the infrastructure is allowed to fall apart, the headquarters become bloated, and visitation stagnates. But they can be fired for getting something wrong in the process. Not very often, but just enough pour encourager les autres, particularly in an environment where there are really no other formal metrics to override this fear.

**postscript: I have found two ways that people who enter government are different from people who enter private business (people are more different at the end of their careers after they have been shaped by the incentives and culture for a long period of time, but I am talking about upon entry into work). First, people who enter government tend to prioritize security (e.g. good benefits, difficult to fire) over other aspects of employment. Note that this just tends to reinforce the risk aversion to making or admitting a mistake even more. Second, people who enter government tend to be more confident of government solutions to problems and more skeptical of private solutions than people who enter private business. This latter is another reason why my company, that offers private solutions for traditional government functions, hears "no" a lot.