The Big Government Trap: Does Stimulus Require Government Spending to Continuously Rise?

There has been a lot of back and forth over the last few years about "austerity". I have wondered how government spending levels over the last few years that dwarf any peacetime levels in history could be called "austerity", but that is exactly what folks like Paul Krugman have been doing. Apparently, the new theory is that the level of spending is irrelevant to stimulus, and only the first derivative matters. In other words, high spending is not stimulative unless it is also increasing year by year. Kevin Drum provides an explanation of this position:

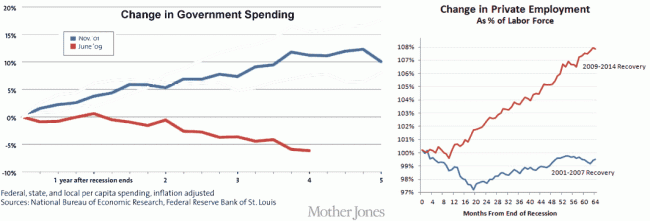

Austerity is all about the trajectory of government spending, and this is what it looks like. You can argue about whether flat spending represents austerity, but a sustained decline counts in anyone's book. The story here is simple: for a little while, in 2009 and 2010, stimulus spending partially offset state and local cuts, but by the end of 2010 the stimulus had run its course. From then on, the drop in government expenditures was steady and significant. It was also unprecedented. If you run this chart back for 50 years you'll never see anything like it. In all previous recessions and their aftermaths, government spending rose.

So, by this theory of stimulus, the fact that we spent substantially more money in 2010-2014 than in pre-recession years (and are still spending more money) turns out not to be stimulative. The only way government can stimulate the economy is to increase year-over-year per capital real spending every single year.

I will leave macro theory (of which I am increasingly skeptical) to the Phd's. In this case however, Drum's narrative is undermined by his own chart he published a few weeks ago:

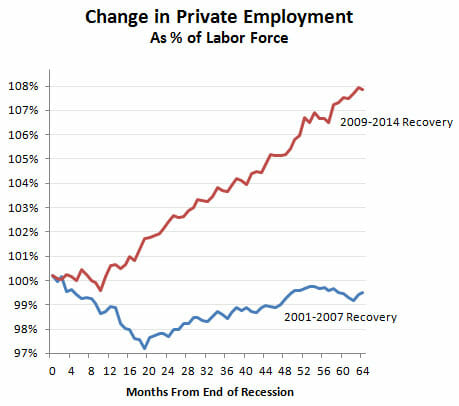

In his recent austerity article quoted above, he describes a sluggish recovery with a step-change in 2014 only after "austerity" ends. But his chart from a few weeks earlier shows a steady recovery from 2010-2014, right through his "austerity" period. In fact, during the Bush recovery he derides, we actually did do exactly what he thinks is stimulative, ie increase government spending per capita steadily year by year. How do we know this? From another Drum chart, this one from last year. I changed the colors (described in this article) and compared his two charts:

By Drum's austerity theory, the Bush spending was stimulative but the Obama spending was austerity. But the chart on the right sure makes it look like the Obama recovery is stronger than the Bush recovery.

A better explanation of the data is that a recession driven by the highly-leveraged mis-allocation of too much capital to home real estate was made worse in 2008-2009 by a massive increase in government spending, which is almost by definition a further mis-allocation of capital (government is taking money from where the private sector thinks it should be invested and moves it to where politicians think it should be spent). The economy has recovered as that increase in government spending has been unwound.

Keynesianism is one long post hoc rationalization for measures already decided upon.

Krugman's article today in the NYT detailing his economic reasons for opposing the keystone pipeline is a classic case of being intellectually inconsistent

Every argument he makes for increased government stimulus spending supports the economic reasons for supporting the keystone pipeline.

Every economic argument he makes against the keystone pipeline devastates the economic argument in favor of deficit stimulus spending.

Somehow - according to Krugman's economic logic, stimulus spending to create temporary construction jobs is good for the economy, but private spending to create temporary construction jobs is bad for the economy.

Who wudda thought krugman could contradict himself in the same paragraph.

so because of the current "leaders" complete incompetency we are doing well when they have tried to ruin us?

The chart showing change in private employment as a % of the labor force is, in my view, pretty much useless (or deliberately misleading), as it does not account for the steady decrease in the number of people in the labor force over the time period shown. In fact, for all we know, the actual change is private employment might actually be negative (I doubt it is, but one cannot tell from the chart). I don't think anyone should show this chart, as it conveys almost no useful information.

I emphatically agree with the main point. It's not "austerity" to continuously spend more money than any single entity in history ever has. High spending is my single greatest source of unease with the competence of the federal government in America. We are supposed to believe that Washington is this magical source of social and economic change, at the same time that it cannot even balance its budget. If they can't handle the basics, why should I believe they're going to do something more ambitious?

On a minor note, I don't think it's a new story that a stimulus has to be fast and unexpected for it to be effective. I was told this over a decade ago the first time anyone walked me through the stimilus argument. The need for speed and surprise is one reason to favor monetary stimulus instead of fiscal: it's much easier to print a bunch of money than it is to come up with useful government programs to spend money on.

Part of the reason to believe you need a spike is that most people seem to think high government spending is generally bad for the economy: it ties up productive resources into what is at best public consumption. Another reason is rational expectations: as soon as everyone in the public can predict what's going to happen with spending and inflation, they account for it in their decisions about prices, wages, and interest rates.

Because of this need for a spike in spending or in the quantity of money, there is an inherent tradeoff with stimulus spending. *At best* you help the economy during the leading edge of the spike. However, you have to either decrease after the spike, or hold at the newer higher level, and both of these are quite bad. A decrease after the spike is the same as an anti-stimulus: it should harm the economy just as much as the leading edgce of the spike was helpful. However, failing to decrease spending is even worse. Now you've tied up the country's resources into government programs, rather than in productive investments.

This tradeoff is much like the use of steroids for pain relief. It works really well at first, but you have to pay a price at some point or another. You can keep it going for a while by steadily increasing the dose, but the more you do that, the more the side effects mount up. It seems easy to me to question whether any form of stimulus is worth the risks, even assuming that Washington is going to implement an optimal stimulus with all the best information and intentions. The case for stimulus gets worse if you consider what tends to happen in practice. Complain about Republicans all you like: is it news to Obama that there are Republicans in Washington? No? Well shouldn't he account for this small detail if he has any idea what's going on in the government?

Stepping back, I am increasingly confused why we are supposed to give national govermnents a free pass on spending patterns that would be clearly irresponsible for either smaller units or for larger ones. The case that it's helping the economy seems murky, both in theory and based on the evidence. The costs, meanwhile, are rather obvious.

Give them a break. The higher government spending gets, the harder it gets to come up with justifications for even more spending that aren't cringe and / or laugh worthy.

As compelling as either the Keynesian or Supply-Side theory is, there are times when other factors swamp fiscal policy. For the last few years, low interest rates (set by the FED, not by the president) and soft oil prices (determined by private investment, not by the president) have spurred the economy and the stock market to a decent recovery. Likewise, the 2008 fiscal crisis was caused by federal housing policy and banking regulations which endured through administration of both policies. These were not fiscal policy issues -- they were regulation issues. Nevertheless, sometimes fiscal policies do move the economy. Almost 85 years ago, fiscal policy of tax increases, severe tariffs and higher government spending, combined with restrictive monetary policy, turned a noteworthy -- but diminishing -- recession into the Great Depression. And Fiscal policy kept us in the Depression for an unprecedented number of years.