Yes, The Federal Campgrounds We Operate Are Open During the Government Shutdown

Several readers have been nice enough to write me and ask how my business is doing during the government shutdown. As background, my company privately operates public recreation areas, mostly campgrounds, under concession contract. We manage public lands for many different government agencies, but many of the campgrounds we run are in the Forest Service. Typically the Forest Service (and National Park Service) must close in this and most other shutdowns. In fact, public parks are often a significant pawn in budget battles, so much so the term "closing the Washington Monument" has become shorthand for using popular public facilities as a leverage point in spending fights (the fact that politicians always threaten to close the MOST popular public services when money is tight rather than the most useless is exhibit A in why we shouldn't trust our money to Congress).

But all the Federal facilities we operate are still open right now through the government shutdown. The reason for this is that our company does not receive a dime from the government -- all the money goes the other way. We operate the facilities essentially under a (very restrictive) lease. We collect visitor use fees and then pay a bid percentage of those fees back to the Feds as our rent -- this is a huge advantage to the government as before our management they typically lost money even after collected visitor fees and now they are gaining money**. Since the government does not have to fund these locations, and since their daily operation requires no federal employees, the parks we operate are typically not closed during government shutdowns.

Long-time readers will be familiar with one exception -- in 2013 during the Obama Administration we were forced to close during a Federal shutdown. Originally, the agencies we work with (particularly the US Forest Service which is part of the Department of Agriculture) gave us the usual guidance, that we were to remain open. Then, suddenly, our company and those like it were told to shut down. When I and my trade group attempted to protest the decision with whatever official in the agency made the decision, we were told it came from "above the Department of Agriculture," which narrows the field of possible decision-makers pretty substantially. My hypothesis, though I can never prove it, was that the Obama Administration wanted to put as much pressure on Congress as possible, and closing the Washington Monument doesn't work as leverage if some damn private company is keeping it open. My competitors and I banded together and took the US Forest Service to court (past articles here) and were in the process of winning our case when the shutdown ended, but ever since then the US Forest Service has allowed us to stay open in shutdowns. If you have WSJ access, they actually covered our effort here; I made an early morning appearance on Fox & Friends; Reason TV did a nice piece; and Hans Bader of the CEI was all over the story and a big help in getting the issue some visibility.

Christmas and New Years are popular times for folks to visit in places like Sedona and Florida where we run Forest Service recreation areas, and we are happy we have been able to stay open and serve them this time around.

**Postscript: This private concession management model also has a benefit in state and local budget battles, though it is slightly different. I can tell you from loooooong personal experience that the public really does not like recreation use fees on public lands. My taxes should pay for that! But now, and certainly in the future, our taxes go mostly to fund programmed expenses like healthcare and welfare plus our bloated military. Anything else is going to be starved -- which leads to the estimated $114 billion in deferred maintenance in federal / state / local public recreation areas and parks ($20+ billion in the National Park Service alone). Seeing this happening, most of the public has become reconciled to user fees for recreation as long as the recreation fee is used to support the local park they are visiting.

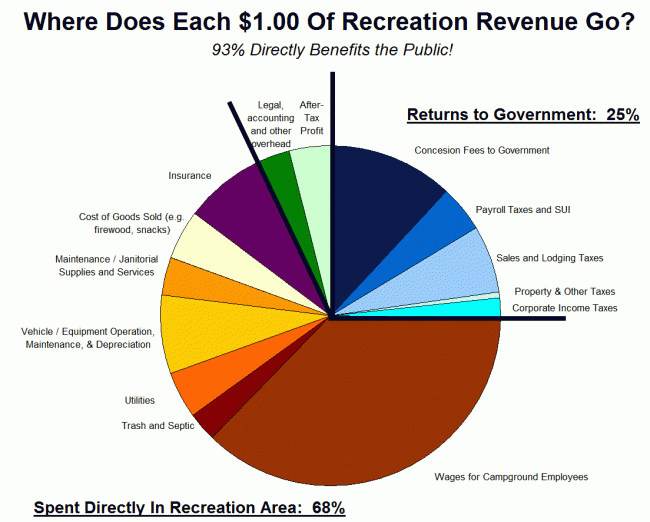

To this end, one reason folks are sometimes leery about private management of these lands is they wonder if their fees are being sucked away to some corporate equivalent of Scrooge McDuck's gold vault rather than supporting operations at the park. It's the reason I keep this chart up on our web site:

In fact, it is the government agencies themselves that often sweep user fees out of the parks and into general revenue funds. The Arizona legislature did this for years to the state parks agency. The result in this situation is that the infrastructure crumbles while the user fees that should be fixing these issues actually has just become another general revenue tax. I think of deferred maintenance in government facilities -- parks, subways, roads, etc -- as a kind of shadow borrowing where government officials borrow against the infrastructure. This borrowing is almost invisible, at least on an incremental basis, and often the debt is eventually defaulted on as the infrastructure is never repaired and has to be closed or torn down. By putting parks under concession management, user fees can no longer be swept away from the management and maintenance of the park, and private companies can often be held accountable for poor maintenance more readily than agencies are able to hold themselves accountable.