Its probably time for another once-every-six-months update on global warming. In this post I will address the current leading climate intervention position, which is: Even if we don't understand global warming fully, the time to take massive action is now, before the process builds momentum (similar to the notion that it is easier to deflect a meteor away from earth when it is millions of miles away, rather than right on top of us). The potential downside of global warming, it is argued, is too high to justify waiting until we are sure.

While I find arguments that attempt to challenge the current global warming orthodoxy in any way tends to get one labeled a Luddite not worth listening to, giving one the feeling of being a southern Baptist advocating creationism in a room full of Massachusetts Democrats, I will once again try to refute this need to immediate and massive intervention.

The shorthand I use for my argument against intervention is "creating a cooler but poorer world". In a nutshell, given current technology and likely government intervention approaches, slowing global warming almost certainly entails slowing world growth. And while the true cost of warming is poorly understood, the true cost of reduced world economic growth is very well understood and is very high. The real question, then, is do we understand global warming and its potential downsides enough to believe that curbing them outweighs the almost certain negative impact from a poorer world.

I will begin by conceding some warming

Typically when making this argument, I will concede some man-made global warming. It is hard to refute the fact from various CO2 concentration estimates that man has increased the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere over the last 50 years, and that this CO2 likely has had and will have some impact on global temperatures. As a result, I am willing to concede a degree or two of warming from man-made effects over the next century. This is lower than most of the warming estimates that you see in the press, but scientists will have to nail down a lot more issues before they can convince me these higher numbers are correct. Some of these issues include:

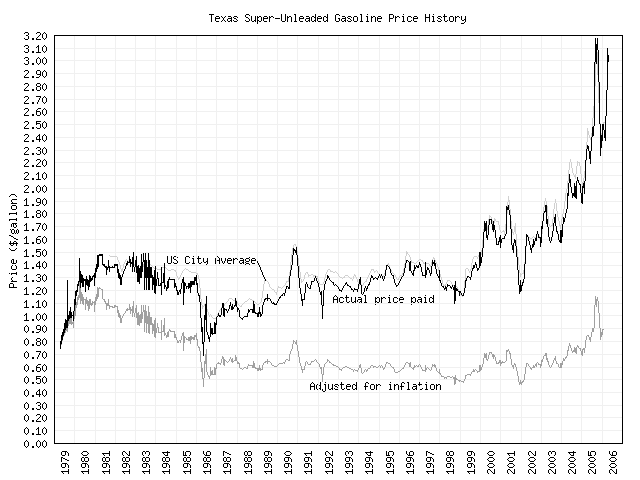

- World temperatures rose by a half degree in the first half of the 20th century through mostly natural phenomena. No one knows why (though solar activity may help explain it), but even global warming's strongest supporters agree that it was probably not due to man. No one can therefore with any accuracy separate warming in the late 20th century due to this natural effect and warming due to man's impact. Check out Mann's now-famous hockey stick below:

Global warming advocates love this chart - I mean this is their chart, not the skeptics' - and it probably plays well with non-scientific editors who are believers themselves, but I sure wouldn't want to defend this in a board room. What if this were a sales chart, and I wanted to claim that the sales increase after I started work in 1950 was all due to my effort. I can just see my old boss Chuck Knight at Emerson, or maybe Larry Bossidy at AlliedSignal, saying - "well Warren, it sure looks like things changed in 1900, not 1950. And whatever was driving things up from 1900 to 1950, why do you think that that effect, which you can't explain, suddenly stopped and your influence took over. And by the way, why did you end your chart with 1998 - I seem to remember 1998 was the peak. Isn't it kind of disingenuous to leave off the last 6 years when the numbers came back down some?" (update: Even in the arctic, where the media writes with so much confidence that global warming is having a measurable impact, the difference between cyclical variations and man-made effects is hard to unravel.)

- No one really understands the cyclical variations in world temperatures and climate. I think it is large, and certainly there are historical records of the last 800 years that seem to point to climactic extremes. Mann, et. al. claim to have shown that man's effects dwarf these natural variations with their 1000-year hockey stick, but there are a lot of problems with Mann, not the least of which is his unbelievably suspicious refusal to release his data and methodology to the scientific community, behavior that would not be tolerated of any other scientist except one who supported the global warming consensus view.

- It is still not clear that the urban heat island effect has been fixed in the ground data, so satellite data tends to show less warming (but some none-the-less).

- The climate models are absurd in ways even a non-climatologist can figure out. For example, economies in energy inefficient undeveloped nations are assumed to grow like crazy in the IPCC scenarios, such that "then the average income of South Africans will have overtaken that of

Americans by a very wide margin by the end of the century. Because of

this economic error, the IPCC scenarios of the future also suggest that

relatively poor developing countries such as Algeria, Argentina, Libya,

Turkey, and North Korea will all surpass the United States."

- I no longer trust the scientific community on global warming. This quote from National Center for Atmospheric Research (NOAA) researcher and global warming action promoter, Steven Schneidersays it all:

We have to offer up scary scenarios, make simplified, dramatic

statements, and make little mention of any doubts we have. Each of us

has to decide what the right balance is between being effective and

being honest.

While many serious scientists are working on the issue, 100% of the anti-growth, anti-technology, anti-America, and anti-man folks have jumped strongly on the global warming bandwagon, and many of these folks have in fact grabbed the reins, leading major efforts and groups. It is important to note that these folks do not care about scientific accuracy or facts. Their agenda is completely and absolutely to use global warming as their lead issue to push their anti-growth agenda. As such, none of these folks are going to tolerate any fact, study, or scientific voice that in any way questions the global warming orthodoxy. And can any scientist be considered serious who uttered the following statement (from the UN's IPCC Conference Summary, page 2):

"It is

likely that, in the Northern Hemisphere, ... 1998 [was] the warmest year during the past thousand years."

My physics instructors in college used to criticize us students constantly for not understanding the error range in our lab work. I wonder what they would think of a group of scientists that stated with confidence that 1998 was the warmest year in the last one thousand, when they only have direct measurement for the last 100 years or so and even then over only a small percentage of the planet and the other 900 years are estimated from tree rings and ice cores. I am tired of being criticized as a Luddite for challenging "scientists" who think they know with confidence the exact world temperature since Charlemagne.

Anyway, to avoid getting bogged down in this mess, I am willing to posit some man-made warming, say 1-2 degrees over the next 100 years. For most who argue the subject, this is the end of the discussion. For me, it is just the beginning.

What impact, warming?

Beyond bad cinema and Sunday supplement hyperbole, its difficult to find the good science aimed at quantifying the impacts, positive and negative, from global warming. In fact, it is impossible in any venue at any level of quality to find any mention of the positive impacts of warming, though anyone with half a brain can imagine any number of positive impacts (e.g. longer growing seasons in cold climates) that will at least partially offset warming negatives.

Now, I am sure many scientists would respond that climate is complicated, and its hard to judge what will happen. Which I believe is true. But surely the same scientists that can cay that the world will warm by x degrees with enough certainty to demand that billions or even trillions of dollars be spent to change energy use should be able to come to some conclusions about the net effects, both positive and negative, from warming.

Certainly sea levels will probably rise, as some ice caps melt, by maybe a foot in the consensus view. And storms and hurricanes may get worse, though its hard to separate the warming effect from the natural cyclical variation in hurricane strength, at least in the Atlantic. What does seem to be clear is that the warming disproportionately will occur in colder, drier climates. For example, a large part of the world's warming will occur in Siberia.

When I hear this, I immediately think longer growing seasons in cold climates plus less impact in already warm climates = more food worldwide. It strikes me that since the climate models tend to spit out warming not only world wide but by area of the world, it would be fairly easy to translate this into an estimate of net impact on food production. This seems to be such an obvious area of study that I can only assume it has been done, and, since we have not heard about it, that the answer from global warming was "increased food production". Since this conclusion neither supports scary headlines, increased grant money, or the anti-growth agenda, no one really talks about it or studies it much. I would bet that if I took all the studies and grants today aimed at quantifying the impact of global warming, more than 95% of the work, maybe 100% of the work, would be aimed solely at negative impacts, studiously ignoring any positive counter-veiling effects.

I often get looks from global warming advocates like I am from Mars when I suggest work needs to be done to figure out how bad warming is, or even if it is really that bad at all. I have learned that there are typically two reasons for this reaction:

- I am talking to one of the anti-growth types, for whom the global warming issue is but a means to the end of growth limitation. These folks need global warming to be BAD as a fundamental premise, not as something that can be fact-checked. They cannot have people questioning that global warming is the ultimate bad thing that trumps everything else anymore than the Catholic Church can have folks start to question the fallibility of the Pope.

- I am talking to an environmentalists who considers man's impact impact on earth as bad, period. It is almost an aesthetic point of view, that it is fundamentally upsetting to see man changing the earth in such a measurable way, irregardless of whether the change affects man negatively. These are the same folks with whom you cannot argue about caribou in ANWR. They don't oppose ANWR drilling because they honestly think the caribou will be hurt, but because they like the notion that there is a bunch of land somewhere that man is not touching

By the way, though I know this will really mark me as an environmental Luddite, does anyone really believe that in 100 years, if we've really screwed ourselves by making things too hot, that we couldn't find a drastic way to cool the place off? Krakatoa's eruption put enough dust in the air to cool the world for a decade. The world, unfortunately, has a lot of devices that go bang laying around that I bet we could employ to good effect if we needed to put some dust in the stratosphere to cool ourselves off. Yeah, I am sure that there are hidden problems here but isn't it interesting that NO ONE in global warming, inc. ever discusses any option for solving warming except shutting down the world's economies?

What impact, Intervention?

While the Kyoto treaty was a massively-flawed document, with current technologies a Kyoto type cap and trade approach is about the only way we have available to slow or halt CO2 emissions. And, unlike the impact of warming on the world, the impact of such a intervention is very well understood by the world's economists and seldom in fact disputed by global warming advocates. Capping world CO2 production would by definition cap world economic growth at the rate of energy efficiency growth, a number at least two points below projected real economic growth. In addition, investment would shift from microprocessors and consumer products and new drug research and even other types of pollution control to energy. The effects of two points or more lower economic growth over 50-100 years can be devastating:

- Currently, there are perhaps a billion people, mostly in Asia, poised to exit millenia of subsistence poverty and reach the middle class. Global warming intervention will likely consign these folks to continued poverty. Does anyone remember that old ethics problem, the one about having a button that every time you pushed it, you got a thousand dollars but someone in China died. Global warming intervention strikes me as a similar issue - intellectuals in the west feel better about man being in harmony with the earth but a billion Asians get locked into poverty.

- Lower world economic growth will in turn considerably shorten the lives of billions of the world's poor

- A poorer world is more vulnerable to natural disasters

- The unprecedented progress the world is experiencing in slowing birth rates, due entirely to rising wealth, will likely be reversed. A cooler world will not only be poorer, but likely more populous as well. It will also be a hungrier world, particularly if a cooler world does indeed result in lower food production than a warmer world

- A transformation to a prosperous middle class in Asia will make the world a much safer and more stable place, particularly vs. a cooler world with a billion Asian poor people who know that their march to progress was halted by western meddling.

- A cooler world would ironically likely be an environmentally messier world. While anti-growth folks blame all environmental messes on progress, the fact is that environmental impact is a sort of inverted parabola when plotted against growth. Early industrial growth tends to pollute things up, but further growth and wealth provides the resources and technology to clean things up. The US was a cleaner place in 1970 than in 1900, and a cleaner place today than in 1970. Stopping or drastically slowing worldwide growth would lock much of the developing world, countries like Brazil and China and Indonesia, into the top end of the parabola. Is Brazil, for example, more likely to burn up its rain forest if it is poor or rich?

The Commons Blog links to this study by Indur Goklany on just this topic:

If global warming is real and its effects will one day be as devastating as

some believe is likely, then greater economic growth would, by increasing

greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, sooner or later lead to greater damages from

climate change. On the other hand, by increasing wealth, technological

development and human capital, economic growth would broadly increase human

well-being, and society's capacity to reduce climate change damages via

adaptation or mitigation. Hence, the conundrum: at what point in the future

would the benefits of a richer and more technologically advanced world be

canceled out by the costs of a warmer world?

Indur Goklany attempted to shed light on this conundrum in a recent paper

presented at the 25th Annual North American Conference of the US Association for

Energy Economics, in Denver (Sept. 21, 2005). His paper "” "Is a

richer-but-warmer world better than poorer-but-cooler worlds?" "” which can

be found here, draws

upon the results of a series of UK Government-sponsored studies which employed

the IPCC's emissions scenarios to project future climate change between 1990 and

2100 and its global impacts on various climate-sensitive determinants of human

and environmental well-being (such as malaria, hunger, water shortage, coastal

flooding, and habitat loss). The results indicate that notwithstanding climate

change, through much of this century, human well-being is likely to be highest

in the richest-but-warmest world and lower in poorer-but-cooler worlds. With

respect to environmental well-being, matters may be best under the former world

for some critical environmental indicators through 2085-2100, but not

necessarily for others.

This conclusion casts doubt on a key premise implicit in all calls to take

actions now that would go beyond "no-regret" policies in order to reduce GHG

emissions in the near term, namely, a richer-but-warmer world will, before too

long, necessarily be worse for the globe than a poorer-but-cooler world. But the

above analysis suggests this is unlikely to happen, at least until after the

2085-2100 period.

Policy Alternatives

Above, we looked at the effect of a cap and trade scheme, which would have about the same effect as some type of carbon tax. This is the best possible approach, if an interventionist approach is taken. Any other is worse.

The primary other alternative bandied about by scientists is some type of alternative energy Manhattan project. This can only be a disaster. Many scientists are technocratic fascists at heart, and are convinced that if only they could run the economy or some part of it, instead of relying on this messy bottom-up spontaneous order we call the marketplace, things, well, would be better. The problem is that scientists, no matter how smart they are, miss with their bets because the economy, and thus the lowest cost approach to less CO2 production, is too complicated for anyone to understand or manage. And even if the scientists stumbled on the right approaches, the political process would just screw the solution up. Probably the number one alternative energy program in the US is ethanol subsidies, which are scientifically insane since ethanol actually increases rather than reduces fossil fuel consumption. Political subsidies almost always lead to investments tailored just to capture the subsidy, that do little to solve the underlying problem. In Arizona, we have thousands of cars with subsidized conversions to engines that burn multiple fuels but never burn anything but gasoline. In California, there are hundreds of massive windmills that never turn, having already served their purpose to capture a subsidy. In California, the state bent over backwards to encourage electric cars, but in fact a different technology, the hybrid, has taken off.

Besides, when has this government led technology revolution approach ever worked? I would say twice - once for the Atomic bomb and the second time to get to the moon. And what did either get us? The first got us something I am not sure we even should want, with very little carryover into the civilian world. The second got us a big scientific dead end, and probably set back our space efforts by getting us to the moon 30 years or so before we were really ready to do something about it or follow up the efforts.

If we must intervene to limit CO2, we should jack up the price of fossil fuels with taxes, or institute a cap and trade scheme which will result in about the same price increase, and the market through millions of individual efforts will find the lowest cost net way to reach whatever energy consumption level you want with the least possible cost. (The only real current alternative that is rapidly deploy-able to reduce CO2 emissions anyway is nuclear power, which could be a solution but was killed by...the very people now wailing about global warming.)

Conclusion

I would like to see some real quality discussion as to the relative merits of the path the world is on today vs. an interventionist world that is cooler but poorer, more populous, hungrier, and less politically stable. If anyone knows of some thoughtful work in this area, please leave a link in the comment area or in my email.

By the way, I got through this whole post without mentioning or quoting Bjorn Lomborg, which really is not fair since he has been very eloquent about just this cooler but poorer argument, but since he is treated like the anti-Christ by global warming believers, it generally only causes people to stop listening when you mention him.

Note finally that other past articles in this series can be found here and here and here.

Disclosure: I am not funded in any way by the automobile or electric power industry. In fact, my personal business

actually benefits from higher oil prices, since our recreation sites

tend to be near-to-home alternatives for those who can't afford to

drive across country, so global warming intervention would probably help me in the near term. However, I do own a fair amount of Exxon-Mobil stock, so you may assume that all my opinions are tainted, following the tried and true Global Warming formula that any money from the energy industry is automatically tainting, but incentives that tie grant money, recognition, or press exposure to the magnitude of warming a scientist predicts never carry a taint. My opinions carry with them an honest concern for the well-being of non-Americans, like the Chinese, which I'm told used to be considered a liberal value until liberals and progressives decided more recently that they actually fear and oppose economic growth in places like China.