The United States Is Doing Better Than Europe on Poverty: An Economics Rorschach Test

Kevin Drum, in commenting on a Binyamin Appelbaum article in the NY Times, writes that the Presidential candidates should be talking more about poverty in part because the US is way behind Europe. Specifically, Appelbaum quotes a Harvard Sociology (!) Professor as the source for the poverty claim:

“We don’t have a full-voiced condemnation of the level or extent of poverty in America today,” said Matthew Desmond, a Harvard professor of sociology. “We aren’t having in our presidential debate right now a

serious conversation about the fact that we are the richest democracy in the world, with the most poverty. It should be at the very top of the agenda.”

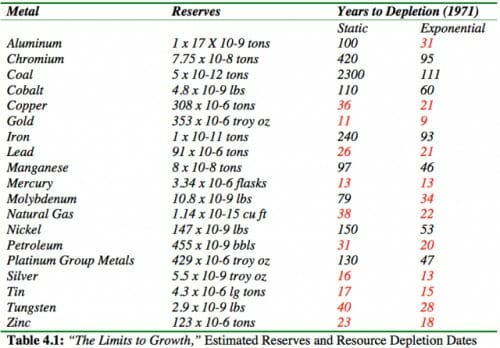

Drum argues that Desmond is right, because of this chart from the OECD:

One of the dirty secrets about poverty measurement is that the actual measurement seldom has anything to do with absolute well-being. And this is the case with the OECD numbers. The OECD's poverty measurement is based on the country's median income, and is the percentage of people who are below a certain percentage (generally 50%) of the country's own median income. As such, this is more rightly thought of as a graph of income inequality rather than absolute poverty.

Here is an example. Image country A with a median income of $50,000 and an income of the 20th percentile at $20,000. Now imagine country B where the median income is $30,000 and the 20th percentile income is $15,000. In this example, the poorest 20th percentile in country A are better off on an absolute basis, but the OECD (and most other poverty numbers) will show country B doing better because the poor are closer to the (much lower) median income. In an extreme example, if everyone in a country were equally impoverished, the OECD would show that country as doing the best on poverty -- Yes, you read that right. By this metric, the OECD would show a country where every person made just $10,000 a year as having 0% poverty.

Obviously, what one would really like to do is compare across nations the absolute well-being of the lowest 10th or 20th percentile. On a purchasing power parity basis, which country's poor has, after transfers and taxes, more money? Unfortunately, you likely have never ever seen this. Yes, the data comparison is hard, but it is possible, so one has to wonder if there is some ulterior political motive for never showing this quite obvious analysis.

I tried to do this analysis myself for years (I describe some false starts here) but was unsuccessful until I actually identified a data source that would work, ironically from two folks on the Left (Kevin Drum and John Cassidy) who were using data from the LIS Cross-National Data Center to make comparisons of income inequality. It turned out the data they were using could do what I wanted.

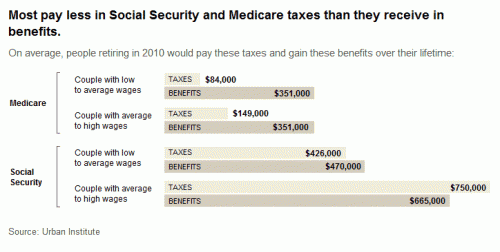

So now we get to the chart I call the poverty Rorschach test. It is a comparison of the absolute income, by income percentile and including transfers and taxes, of the US vs. Denmark (the country by Drum's chart that should be the "best" on poverty)

(The date is old, alas, because this kind of cross-country data is only gathered every so often)

This chart shows, on a purchasing power parity basis, that for every single income percentile, all the way to the bottom, an equivalent person in the US has more income than that a similarly situated person in Denmark. In short, the poor in the US are wealthier than the poor in Denmark. The only reason Denmark does better than the US in the way the OECD and others measure poverty is that the middle class in the US are a LOT wealthier than the middle class in Denmark.

I call it the Rorschach test because one either sees the US doing a good job, because everyone is better off, or the Danish doing a better job, because everyone is more even. Proponents of the latter view tend to believe that the size of the economic pie is an exogenous variable, unrelated to the method one chooses to slice it.

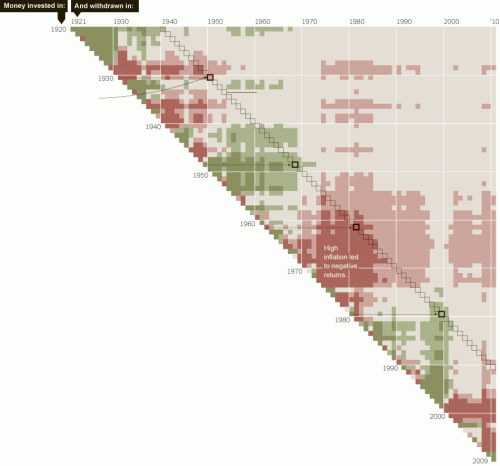

I picked the Danish because they were the obvious comparison from Drum's chart, but here is the US vs. all the European countries for which there was data in the survey. The US is better than all but 3 at the 10th percentile and better than all but one country at the 20th percentile. And better -- by a huge margin-- for the middle class than any of the countries in Europe.

Update: One more note on Drum's chart. As I said above, the exact definition of the OECD numbers is percentage of people with income less than 50% of the country's own median income. The US has a median household income, per the OECD, 41% higher than Denmark's. So the US has 9% more people under a number that is 41% higher. That is hardly a fair or meaningful comparison.

For reasons that are beyond my understanding, I am banned at Mother Jones so I cannot post the comments directly to his article. If someone wanted to cut and paste this under his or her own name, I wouldn't complain.