Understanding "Mix": Is Flattening in Income Growth Due in Part to Geographic Cost of Living Differences and Migration Within the US?

For 20 years, before I liberated myself from corporate America, I spent a hell of a lot of time doing business and market analysis (e.g. why are profits declining in Division X). I was pretty good at it. If I had to boil down everything I learned in those years to one lesson, it would be this: Pay attention to changes in the mix.

What do I mean by "changes in the mix"? Here is an example. A company has two products. One has a 20% margin, and the other has a 30% margin, and both margins have been improving over time because of a series of cost reduction investments. But overall, company margins are falling. The likely reason: the mix is shifting. The company is selling a higher proportion of the lower margin product.

Here is a real world example: When I was at AlliedSignal (now Honeywell) aviation, they had exactly this problem. They were operating in a razor and blades business -- ie they practically gave the new parts away to Boeing and Airbus to put on their planes, because they made all their money selling aftermarket replacements at a premium (at the time, government rules made it almost impossible to buy anything but the original manufacturer's part, so they could charge almost anything for a replacement, especially given that an airline likely had a $50 million plane sitting dormant until the part was replaced). I routinely would tell managers in the company that essentially our business made money from unreliability -- the less reliable our parts, the more money we made. Because newer technology, competition, and pressure form airlines was forcing us to greatly improve our reliability (at the same time we were giving stuff to Boeing at ever greater losses), all our newer products on newer planes were less profitable than the old stuff. As planes aged and dropped out of the fleet, our product mix was getting less and less profitable.

This same effect can be seen in many economic and political issues. Take for example an argument my mother-in-law and I had years and years ago. She said that Texas (where I was living at the time) had crap schools that were much worse that those in Massachusetts, her argument for the blue political model. She observed that average educational outcomes were much better in MA than TX (which was and still is true). I observed on the other hand that this was in part a result of mix. Texas had better outcomes than MA when one looked at Hispanics alone, and better outcomes for non-Hispanics alone, but got killed on the mix given that Hispanics typically have lower educational outcomes than non-Hispanics everywhere in the US, and Texas had far more Hispanics than MA.

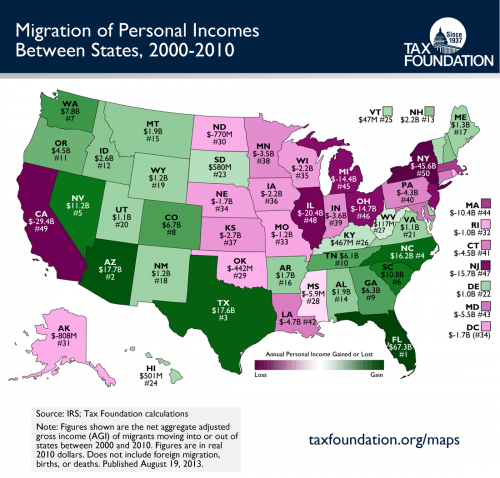

All of this is a long introduction to some thinking I have been doing on all the "Average is Over" discussion talking about the flattening of growth in median wages. I begin with this chart:

There is a lot of interstate migration going on. And much of it seems to be out of what I think of as higher cost states like CA, IL, and NY and into lower cost states like AZ, TX, FL, and NC. One of the facts of life about the CPI and other inflation adjustments of income numbers is that the US essentially maintains one average CPI. Further, median income numbers and poverty numbers tend to assume one single average cost of living number. But everyone understands that the income required to maintain lifestyle X on the east side of Manhattan is very different than the income required to maintain lifestyle X in Dallas or Knoxville or Jackson, MS.

Could it be that even with a flat average median wage, that demographic shifts to lower cost-of-living states actually result in individuals being better off and living better?

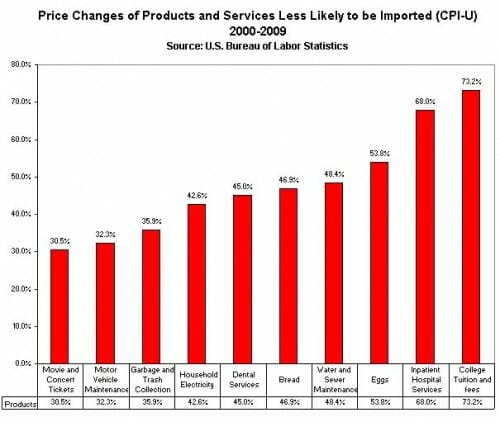

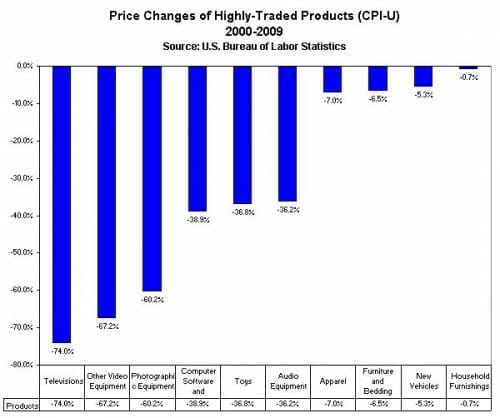

For some items one buys, of course, there is no improvement by moving. For example, my guess is that an iPhone with a monthly service plan costs about the same anywhere you go in the US. But if you take something like housing, the differences can be enormous.

Let's compare San Francisco and Houston. At first glance, San Francisco seems far wealthier. The median income in San Francisco is $78,840 while the median income in Houston in $55,910. Moving from a median wage job in San Francisco to a media wage job in Houston seems to represent a huge step down. If you and a bunch of your friends made this move, the US median income number would drop. It would look like people were worse off.

But something else happens when you take this nominal pay cut to move to Houston. You also can suddenly afford a much nicer, larger house, even at the lower nominal pay. In San Francisco, your admittedly higher nominal pay would only afford you the ability to buy only 14% of the homes on the market. And the median home, which you could not afford, has only about 1000 square feet of space. In Houston, on the other hand, your lower nominal pay would allow you to buy 56% of the homes. And that median home, which you can now afford, will have on average 1858 square feet of space.

So while the national median income numbers dropped when you moved to Houston, you actually can afford a much nicer home with perhaps twice as much space. Thus, it strikes me that there are important things happening in the mix that are not being taken into account when we say that the "average is over".

Of course, while this effect is certainly real, I have no idea how much it affects the overall numbers, ie is it a small effect or a large effect. Fortunately my son is studying economics in college. If he ever goes to grad school, I will add this to my list of research suggestions for him.

Postscript: This exact same discussion could apply to US poverty statistics. We have one poverty line income number whether you live in Manhattan or Tuscaloosa. I have always wondered how much poverty statistics would change if you created some kind of purchasing power parity test rather than a fixed income test.