The table of contents for the rest of this paper, . 4A Layman's Guide to Anthropogenic Global Warming (AGW) is here. Free pdf of this Climate Skepticism paper is here and print version is sold at cost here

Kyoto Treaty

In the mid-1990's, a number of western nations crafted a CO2-reduction

treated named Kyoto for the city in which the key conference was held.

The treaty called for signatory nations to roll back their CO2 emissions to

below 1990 levels by a target date of 2012. Japan, Russia, and many

European nations signed the treaty; the United States did not. In fact,

the pact was ratified by 141 nations, but only calls for CO2 limits in 35 of

these (so the other 106 were really going out on a limb signing it).

China, India, Brazil and most of the third world are exempt from its limits.

We will discuss the costs and benefits of CO2 reduction a bit later.

However, it is instructive to look at why Kyoto was crafted the way it was, and

why the United States refused to sign, even when Al Gore was vice-president.

The most obvious flaw is that the entire developing world, including China,

SE Asia, and India, are exempt. These countries account for 80% of the world's

population and the great majority of growth in CO2 emissions over the next few

decades, and they are not even included. If you doubt this at all, just look at

what the economic recovery in China over the past months has done to oil

prices. China's growth in

hydrocarbon consumption will skyrocket over the coming years, and China is

predicted to have higher CO2 production than the United States by 2009.

The second major flaw with the treaty is that European nations cleverly

crafted the treaty so that the targets were relatively easy for them to make,

and very difficult for the United States to meet. Rather than freezing

emissions at current levels at the time of the treaty, or limiting carbon

emission growth rates, the treaty called for emissions to be rolled back to

below 1990 levels. Why 1990? Well, a couple of important things have happened

since 1990, including:

a. European (and Japanese) economic growth has stagnated since 1990, while

the US economy has grown like crazy. By setting the target date back to 1990,

rather than just starting from day the treaty was signed, the treaty

effectively called for a roll-back of economic growth in the US that other

major world economies did not enjoy.

b. In 1990, Germany was reunified, and Germany inherited a whole country

full of polluting inefficient factories from the old Soviet days. Most of the

dirty and inefficient Soviet-era factories have been closed since 1990, giving

Germany an instant one-time leg up in meeting the treaty targets, but only if

the date was set back to 1990, rather than starting at the time of treaty

signing.

c. Since 1990, the British have had a similar effect from the closing of a

number of old dirty Midlands coal mines and switching fuels from very dirty

coal burned inefficiently to more modern gas and oil furnaces and nuclear

power.

d. Since 1990, the Russians have an even greater such effect, given low

economic growth and the closure of thousands of atrociously inefficient

communist-era industries.

It is flabbergasting that US representatives could allow the US to get so

thoroughly out-manuevered in these negotiations. Does anyone in the US really

want to roll back the economic gains of the nineties, while giving the rest of

the world a free pass? Anyway, as a result of these flaws, and again having

little to do with the global warming argument itself, the Senate

voted 95-0 in 1997 not to sign or ratify the treaty unless these flaws (which

still exist in the treaty) were fixed. Then-Vice-President Al Gore

agreed that the treaty should not be signed without modifications, which were

never made and which Europeans were never going to make.

By the way, enough time has elapsed that we have data on the

progress of various countries in meeting these targets. And if you leave

out various accounting games with offsets of dubious value, most all the

European nations, despite all the advantages described above, are still missing

their targets. The political will simply does not exist to hamstring

their economies to the extent necessary to roll back CO2 growth. Actual

growth rates for CO2 emissions have been (source UN):

|

|

United States

|

Europea Union

|

|

1990-1995

|

6.4%

|

-2.2%

|

|

1996-2000

|

10.1%

|

2.2%

|

|

2001-2004

|

2.1%

|

4.5%

|

You can see that the Europeans positioned themselves well in

the 1990's to make their targets. Realize that as the treaty was negotiated,

they already had a good idea of these numbers for 1990-1995 and even a few

years beyond. They knew that by selecting a 1990 baseline, they were

already on target to meet the goals and the US would be far behind.

Again, realize that the 1990-2000 EU performance on CO2 production had nothing

to do with post-Kyoto regulatory responses and everything to do with the

economic fundamentals we outlined above that would have existed with or without

the treaty.

Since 2000, however, it has been a different story.

European emissions have increased as their economies have recovered, at the

same time the US experienced a post-9/11 slowdown.

By the way, the US is generally the great Satan in AGW

circles because its per capita CO2 production is the highest in the

world. But this is in part because our economic output per capita is

close to the highest in the world. The US is about in

the middle of the pack in efficiency, though behind many European countries

which have much higher fuel taxes and heavier nuclear investments.

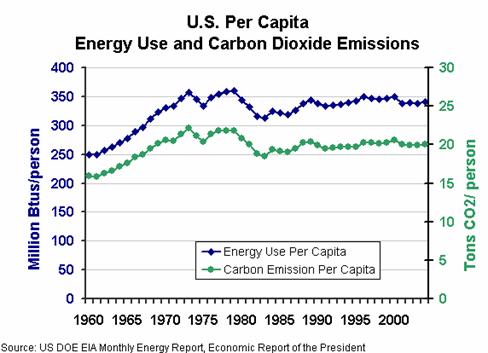

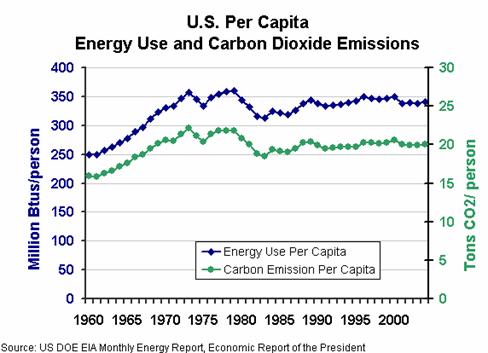

As an interesting side note, the US per capita CO2

emissions, as show below, have actually been flat to down since the early

1970's. To the extent that Europe is doing better at CO2 reduction than

the US, it may actually be more of an artifact of their declining populations

vs. America's continued growth.

Finally, if you get really tired of the US-bashing, you can

take some comfort that though the US is the #1 per capita producer of CO2, of

which we are uncertain is even harmful, we have done a fabulous job reducing

many other pollutants we are much more certain are harmful. For example,

the US has much lower SO2

production than most European nations and the

water quality is better. One could argue that the US has spent its

abatement dollars on things that really matter.

Cost of the

Solutions vs. the Benefits: Why Warmer but Richer may be Better than

Colder and Poorer

If you get beyond the hard core of near religious believers in the massive

warming scenarios, the average global warming supporter would answer this paper

by saying: "Yes there is a lot of uncertainty, but though the doomsday

warming scenarios via runaway positive feedback in the climate can't be proven,

they are so bad that we need to cut back on CO2 production just to be on the

safe side."

This would be a perfectly reasonable approach if cutting back on CO2

production was nearly cost-free. But it is not. The burning of

hydrocarbons that create CO2 is an entrenched part of our lives and our

economies. Forty years ago we might have had an easier time of it, as we were

on a path to dramatically cut back on CO2 production via what is still the only

viable technology to massively replace fossil fuel consumption -- nuclear

power. Ironically, it was environmentalists that shut down this effort,

and power industries around the world replaced capacity that would have gone

nuclear mostly with coal, the worst fossil fuel in terms of CO2 production (per

BTU of power, Nuclear and hydrogen produce no CO2, natural gas produces some,

gasoline produces more, and coal produces the most).

Just halting CO2 production at current levels (not even rolling it back)

would knock several points off of world economic growth. Every point of

economic growth you knock off guarantees you that you will get more poverty,

more disease, more early death. If you could, politically, even make such

a freeze stick, you would lock China and India, nearly 2 billion people, into

continued poverty just when they were about to escape it. You would in

the process make the world less secure, because growing wealth is always the

best way to maintain peace. Right now, China can become wealthier from

peaceful internal growth than it can from trying to loot its neighbors.

But in a zero sum world created by a CO2 freeze, countries like China would

have much more incentive to create trouble outside its borders. This

tradeoff is often referred to as a cooler but poorer world vs. a richer but

warmer world. Its not at all clear which is better.

What impact, warming?

We've already discussed just how much the popular media has overblown the

effect of warming. Sea levels may rise, but only by 15 inches in one

hundred years, and even that based on arguably over-inflated IPCC models.

There is no evidence that weather patterns will be more severe, or that

diseases will spread, or that species will be threatened by warming. And,

since most of the warming has been and will be concentrated in winter and

nights, we will see rising temperatures more in a narrowing of temperature

variability rather than a drastic increase in summer high temperatures.

Growing seasons, in turn, will be longer and deaths from cold, which tend to

outnumber heat-related deaths, will decline.

What impact, Intervention?

While the Kyoto treaty was a massively-flawed document, with current

technologies a Kyoto type cap and trade approach is about the only way we have

available to slow or halt CO2 emissions. And, unlike the impact of

warming on the world, the impact of such a intervention is very well understood

by the world's economists and seldom in fact disputed by global warming

advocates. Capping world CO2 production would by definition cap world

economic growth at the rate of energy efficiency growth, a number at least two

points below projected real economic growth. In addition, investment

would shift from microprocessors and consumer products and new drug research

and even other types of pollution control to energy. The effects of two points

or more lower economic growth over 50-100 years can be devastating:

- Remember the power of compounded growth rates we discussed earlier. A world real economic growth rate of 4% yields income fifty times higher in a hundred years. A world real economic growth rate two points lower yields income only 7 times higher in 100 years. So a two point reduction in growth rates reduces incomes in 100 years by a factor of seven! This is enormous. It means, literally, that on average everyone in a cooler world would make 1/7 what they would make in a warmer world.

- Currently, there are perhaps a billion people, mostly in Asia, poised to exit millennia of subsistence poverty and reach the middle class. Global warming intervention will likely consign these folks to continued poverty. Does anyone remember that old ethics problem, the one about having a button that every time you pushed it, you got a thousand dollars but someone in China died. Global warming intervention strikes me as a similar issue - intellectuals in the west

feel better about man being in harmony with the Earth but a billion Asians get locked into poverty.

- Lower world economic growth will in turn considerably

shorten the lives of billions of the world's poor

- A poorer

world is more vulnerable to natural disasters. While AGW

advocates worry (needlessly) about hurricanes and tornados in a warmer

world, what we can be certain of is that these storms will be more devastating and kill more people in a poorer world than a richer one.

- The unprecedented progress the world is experiencing in

slowing birth rates, due entirely to rising wealth, will likely be

reversed. A cooler world will not only be poorer, but likely more populous as well. It will also be a hungrier world, particularly if

a cooler world does indeed result in lower food production than a warmer

world

- A transformation to a prosperous middle class in Asia will

make the world a much safer and more stable place, particularly vs. a cooler world with a billion Asian poor people who know that their march to progress was halted by western meddling.

- A cooler world would ironically likely be an

environmentally messier world. While anti-growth folks blame all

environmental messes on progress, the fact is that environmental impact is

a sort of inverted parabola when plotted against growth. Early

industrial growth tends to pollute things up, but further growth and

wealth provides the resources and technology to clean things up. The

US was a cleaner place in 1970 than in 1900, and a cleaner place today

than in 1970. Stopping or drastically slowing worldwide growth would

lock much of the developing world, countries like Brazil and China and

Indonesia, into the top end of the parabola. Is Brazil, for example, more likely to burn up its rain forest if it is poor or rich?

The Commons Blog

links to this

study by Indur Goklany on just this topic:

If global warming is real and its effects will one

day be as devastating as some believe is likely, then greater economic growth

would, by increasing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, sooner or later lead to

greater damages from climate change. On the other hand, by increasing wealth,

technological development and human capital, economic growth would broadly

increase human well-being, and society's capacity to reduce climate change

damages via adaptation or mitigation. Hence, the conundrum: at what point in

the future would the benefits of a richer and more technologically advanced

world be canceled out by the costs of a warmer world?

Indur Goklany attempted to shed light on this

conundrum in a recent paper presented at the 25th Annual North American

Conference of the US Association for Energy Economics, in Denver (Sept. 21,

2005). His paper "” "Is a

richer-but-warmer world better than poorer-but-cooler worlds?" "” which can

be found here,

draws upon the results of a series of UK Government-sponsored studies which

employed the IPCC's emissions scenarios to project future climate change

between 1990 and 2100 and its global impacts on various climate-sensitive

determinants of human and environmental well-being (such as malaria, hunger,

water shortage, coastal flooding, and habitat loss). The results indicate that

notwithstanding climate change, through much of this century, human well-being

is likely to be highest in the richest-but-warmest world and lower in

poorer-but-cooler worlds. With respect to environmental well-being, matters may

be best under the former world for some critical environmental indicators through

2085-2100, but not necessarily for others.

This conclusion casts doubt on a key premise

implicit in all calls to take actions now that would go beyond "no-regret"

policies in order to reduce GHG emissions in the near term, namely, a

richer-but-warmer world will, before too long, necessarily be worse for the

globe than a poorer-but-cooler world. But the above analysis suggests this is

unlikely to happen, at least until after the 2085-2100 period.

Policy Alternatives

Above, we looked at the effect of a cap and trade scheme, which would have

about the same effect as some type of carbon tax. This is the best

possible approach, if an interventionist approach is taken. Any other is

worse.

The primary other alternative bandied about by scientists is some type of

alternative energy Manhattan project. This can only be a disaster.

Many scientists are technocratic

fascists at heart, and are convinced that if only they could run the

economy or some part of it, instead of relying on this messy bottom-up

spontaneous order we call the marketplace, things, well, would be better.

The problem is that scientists, no

matter how smart they are, miss with their bets because the economy, and

thus the lowest cost approach to less CO2 production, is too complicated for

anyone to understand or manage. And even if the scientists stumbled on

the right approaches, the political process would just screw the solution

up. Probably the number one alternative energy program in the US is

ethanol subsidies, which are scientifically insane since ethanol

actually increases rather than reduces fossil fuel consumption.

Political subsidies almost always lead to investments tailored just to capture

the subsidy, that do little to solve the underlying problem. In Arizona,

we have thousands of cars with subsidized conversions to engines that burn

multiple fuels but never burn anything but gasoline. In California, there

are hundreds of massive windmills that never turn, having already served their

purpose to capture a subsidy. In California, the state bent over

backwards to encourage electric cars, but in fact a different technology, the

hybrid, has taken off.

Besides, when has this government led technology revolution approach ever

worked? I would say twice - once for the Atomic bomb and the second time

to get to the moon. And what did either get us? The first got us

something I am not sure we even should want, with very little carryover into

the civilian world. The second got us a big scientific dead end, and

probably set back our space efforts by getting us to the moon 30 years or so

before we were really ready to do something about it or follow up the efforts.

If we must intervene to limit CO2, we should jack up the price of fossil

fuels with taxes, or institute a cap and trade scheme which will result in

about the same price increase, and the market through millions of individual

efforts will find the lowest cost net way to reach whatever energy consumption

level you want with the least possible cost. (The only real current

alternative that is rapidly deploy-able to reduce CO2 emissions anyway is nuclear

power, which could be a solution but was killed by...the very people now

wailing about global warming.)

The table of contents for the rest of this paper, . 4A Layman's Guide to Anthropogenic Global Warming (AGW) is here. Free pdf of this Climate Skepticism paper is here and print version is sold at cost here

The open comment thread for this paper can be found here.