Government Supply-Side Health Care Restrictions that Raise Costs

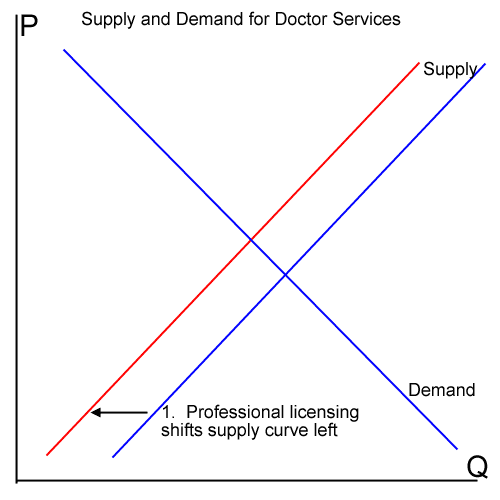

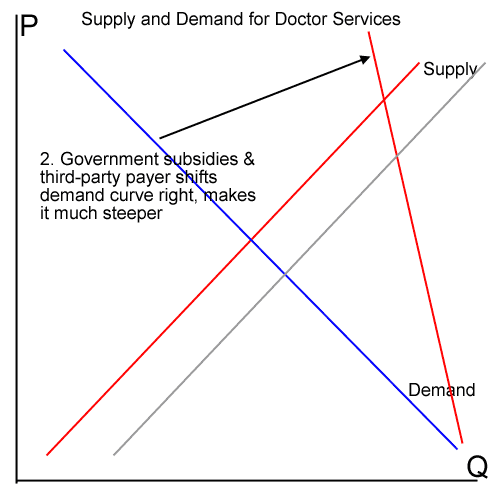

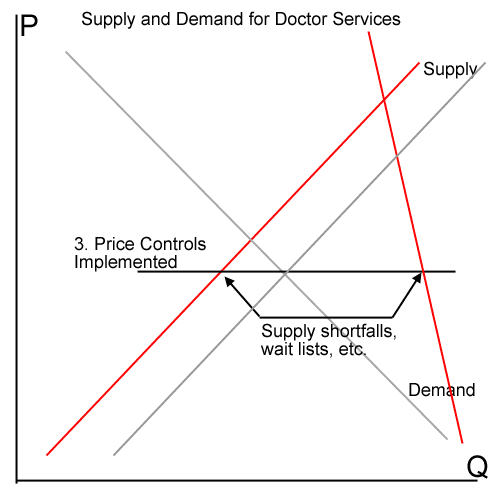

One of the least reported issues related to health care cost inflation is the existence of artificial government restrictions on health care supply, often called "certificates of need".

The COPN [certificate of public need] law is supply-side Obamacare: top-down, command-and-control restrictions on which providers can offer which services. A certificate of public need is, essentially, a government permission slip. Without one, a Virginia doctor can’t put an MRI machine in his clinic. A hospital can’t build a new wing. A hospital company can’t add a satellite campus. And so on.

Getting such permission slips is a long and costly process. The owner of a Northern Virginia radiology practice, for example, spent five years and $175,000 asking permission to buy a new MRI machine. The state said no.

One reason the process takes so long is that competitors often fight such requests. When Bon Secours proposed the St. Francis Medical Center in Chesterfield, rival chain HCA fought it vigorously, arguing there was insufficient demand. The hospital was approved and enjoys a robust business. You’d think state regulators would laugh off competitors’ arguments, but sometimes they’re actually taken seriously. When a Richmond radiology practice wanted to move—not add, but move—a radiation device to its Hanover offices, the state said no in part because Virginia Commonwealth University’s Massey Cancer Center worried the project “could take some of their business.”

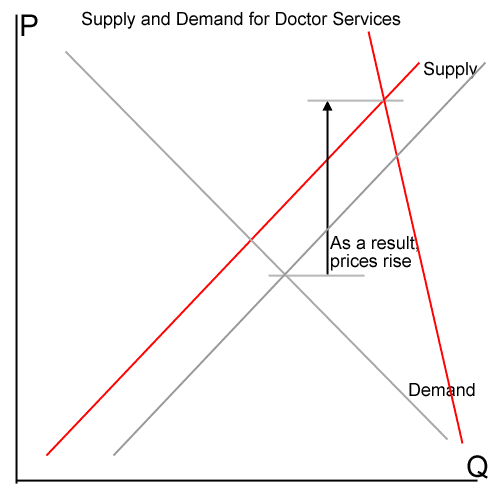

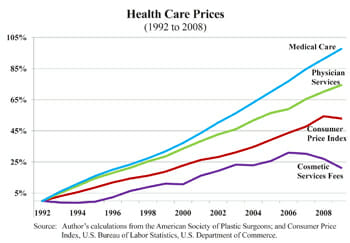

This is cronyism and protection of incumbent competitors, pure and simple. It is often justified by the economically-ignorant as reducing costs because it reduces expenditures on expensive machinery. But in what industry can you think of does restricting supply ever reduce costs?

In any other industry, the proper response to that would be: So what? If Kroger sets up across the street from Food Lion, we consider that good for consumers: They have more choice. And if they migrate from Food Lion to Kroger, that’s not a bad thing. It means they’re getting more utility for their grocery dollar.

Studies of the COPN system around the country have confirmed what seems intuitively obvious. A joint examination by the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission found that COPN regulations hurt competition, fail to contain costs, and “can actually lead to price increases.” Restricting supply raises prices? Imagine that.