Kevin Drum, building on a story from the NY Times, uses data from the California Energy Commission to make the case that California is the most efficient user of electricity in the country and that this efficiency can be attributed sole to government intervention. Drum, always on the lookout for an excuse for the government to take over some sector of the economy, concludes:

Anyway, it's a good article, and goes to show the kinds of things we

could be doing nationwide if conservative politicians could put their

Chicken Little campaign contributors on hold for a few minutes and take

a look at how it's possible to cut energy use dramatically "” and reduce

our dependence on foreign suppliers "” without ruining the economy. The

energy industry might not like the idea, but the rest of us would.

On its face, California's numbers are impressive. The CEC's numbers show California to have the lowest per capita electricity use in the nation, using electricity at half the national rate and one quarter the "least efficient" states.

This would be really cool if it were true that a few simple public policy steps could cut per capital energy consumption in half. Unfortunately, though I am willing to posit California is better than average (as any state would be with a mild climate and newer housing), the data doesn't say what Drum and the article are trying to make it say.

The consumption data is from here. You can see that there are three components that matter - residential, commercial, and industrial. Residential and commercial electricity consumption may or may not be fairly apples to apples comparable between states (more in a minute). Industrial consumption, however, will not be comparable, since the mix of industries will change radically state by state. As an extreme example, states with high aluminum production or oil refining or steel making, which are electricity intensive, will have a higher per capita industrial electricity consumption, irrespective of public policy. The graph Drum and the NY Times uses includes industrial consumption, which is a mistake -- it is more reflective of industry mix than true energy efficiency.

Take two of the higher states on the list. Wyoming, at the top of the per capita consumption list, has industrial electricity consumption as a whopping 58% of total state consumption. KY, also near the top, has industrial consumption at 50% of total demand. The US average is industrial consumption at 29% of total demand. CA, NY, and NJ, all near the bottom of the list in terms of per capital demand, have industrial use as 20.6%, 15.1%, and 16% respectively. So rather than try to correlate electricity consumption to local energy regulations, it is clear that the per capita consumption numbers by state are a much better indicator of the presence of heavy industry. In other words, the graph Drum shows is actually a better illustration of the success of CA not in necessarily becoming more efficient, but in exporting its pollution to other states. No one in their right mind would even attempt to build a heavy industrial plant in CA in the last 30 years. The graph is driven much more by the growth of industrial electricity use outside CA relative to CA.

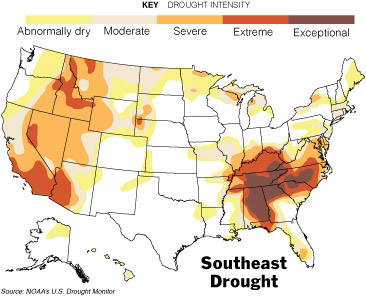

Now take the residential numbers. Lets look again at the states at the top of the per capita list: Alabama, South Carolina, Louisiana, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, Texas. Can anyone tell me what these states have in common? They are hot and humid. Yes, California has its hot spots, but it has its mild spots too (also, California hot spots are dry, so they can use more energy efficient evaporative cooling, something that does not work in the deep south). These southern states are hot all over in the summer. So its reasonable to assume that maybe, just maybe, some of these hot states have higher residential per capita consumption because of air conditioning load? In fact, if one recast this list as residential use per capita, you would see a direct correlation to summer air conditioning loads. This table of cooling degree days weighted for population location is a really good proxy for how much air conditioning is needed by state. (Explanation of cooling degree days). You can see that states like Alabama and Texas have two to four times the number of cooling degree days than California, which should directly correlate to about that much more per capita air conditioning (and thus electricity) use.

In fact, I have direct knowledge of both Alabama and Texas. Both have seen a large increase in residential per capita electricity use vis a vis California over the last thirty years. Granted. But do you know why? The number one reason for increased residential electricity use in the South is the increased access of the poor, particularly poor blacks, to air conditioning. It is odd to see a liberal like Drum railing against this trend. Or is it that he just didn't bother to try to understand the numbers?

OK, now I have saved the most obvious fisking for last. Because even when you correct for these numbers, California is pretty efficient vs. the average on electricity consumption. Drum attributes this, without evidence, to government action. The NY Times basically does the same, positing in effect that CA has more energy laws than any other state and it has the lowest consumption so therefore they must be correlated. But of course, correlation is not equal to causation. Could there be another effect out there?

Well, here are the eight states in the data set above that the California CEC shows as having the lowest per capita electricity use: CA, RI, NY, HI, NH, AK, VT, MA. All right, now here are the eight states from the same data set that have the highest electricity prices: CA, RI, NY, HI, NH, AK, VT, MA. Woah! It's the exact same eight states! The 8 states with the highest prices are the eight states with the lowest per capita consumption. Unbelievable. No way that could have an effect, huh? It must be all those green building codes in CA. I suspect Drum is sort of right, just not in the way he means. Stupid regulation in each state drives up prices, which in turn provides incentives for lower demand. It achieves the goal, I guess, but very inefficiently. A straight tax would be much more efficient.

Please, is there anyone in the "reality-based community" that cares that their data really is saying what they think it is saying??