What Seems To Be Going on At @Tesla, and The Risks Of Buying (and Shorting) $TSLA Stock

I know I have blogged too much about Tesla of late, and you can be forgiven for just skipping on. However, I find the situation fascinating -- I have seen splits between bulls and bears on stocks before, but never a situation where there is such a cultural divide between the two groups. What really caused me to write this article is that I have read a number of naive and idealistic people who have written online that they have invested all their money into Tesla. They love the car, they love Elon Musk, and they are going to trust him with all their money. EEEEEKKK! I am going to give my warnings about not being an investment professional in a minute, but I feel more than comfortable even as a regular guy telling you absolutely DO NOT put all your money into a single investment, particularly one you do not control.

So, disclosures: I am not an investment professional. I have studied the science of dissecting corporations at Harvard Business School, but I have a less than perfect history of actually trying to make money from this knowledge. I am short $tsla via put options (a very small percentage of my portfolio), but shorting a stock like this where there is so much passion on the bull side is dangerous. I and others recognized many of the issues I will discuss in this post over a year ago, but had we been trying to roll puts or sit on a short position all this time it would have gotten very expensive. Making this investment even more risky -- either way, long or short -- is the fact that at this point you are effectively betting on one question: Will Tesla be able to raise new capital in the next 6 months. This is a question even the experts can't handle and as a result it is probably only safe to dabble in Tesla as a bar bet for most.

BTW, since there is a culture war over Tesla that mirrors the larger culture war in this country, criticisms of Tesla are often interpreted as being based on bad motives and evil intentions. So I will say that despite having once worked for Exxon, I am not in the pay of the Kochs or other fossil fuel interests, and don't have an axe to grind over electric cars. I am putting solar on my roof and I have a deposit put down on a Lucid Air. I have a number of renewables investments in my portfolio, e.g. PEGI.

But I believe the reckoning may be coming soon for Tesla. If you understand the risks and it is <5% of your portfolio, fine -- take a flyer. But for any of you that have a lot of money in Tesla and maybe don't have a lot of experience investing or analyzing companies, my advice is get out ASAP. You have a unique opportunity here that despite a lot of red flags and smoking guns, the stock still trades at a level that will get most folks out of their position cleanly.

The Tesla Passion

Tesla has an incredibly passionate customer base that overlaps a lot with its incredibly passionate investor base. This passion is based, in part, on:

- The model S which, when it first came out, was years and years ahead of its time. Every other electric car at the time was a joke -- the model S was a real legitimate luxury sedan one might want even if one did not care about EV's. The later Model X SUV was also pretty good (though in my opinion not as good). The current Model 3 is a mixed bag which we will discuss further. But suffice it to say that Tesla earned the right to be called a leader and an innovator in the field

- Elon Musk. He seems to be passionate about the same things (the environment, hating on oil companies, etc) that his fans are passionate about. He is involved in amazing, super cool stuff like SpaceX. He is constantly coming up with new product and service concepts and promising them to his user base. He responds directly to customer complaints and suggestions and generally promises everyone that they can have their fix or feature really soon. He has created a mythology that he is Tony Stark incarnate, and many of his fans honestly believe him to be the smartest man on Earth.

- Comparisons to Apple. Elon Musk and his fans frequently argue that they are reinventing the auto industry as Apple. with the implicit assumption that they will shift historically low auto gross margins to be like Apple's crazy-high gross margins. How this will happen is left a little vague, but among other things there is a vision of the car as a software platform, where consumers pay recurring fees for a stream of over-the-air features and updates.

- Self-Driving. Tesla fans are convinced that they are just days away from having full automated self-driving features in their Tesla. Many paid thousands of dollars on faith for this feature and continue to wait patiently for it to be delivered (which it has not been), even years after paying for it. It is an article of faith among Tesla fans that Tesla is years ahead of every other self-driving competitor because the smartest guy in the world is running the program.

- The sales process. The sales process (which is mostly online) seems much friendlier and less intimidating than going in to a dealer, and non-commissioned Tesla employees in their small showrooms seem much more likeable to the average Tesla buyer than the average car salesman.

- Every quarter, promised new products. Elon Musk is an absolute fountain of new product ideas. Reading his Twitter feed is like looking through Popular Mechanics covers in the 1970s. Solar roof tiles! Sending a man to the Moon! Martian colony! Electric Semi! Electric pickup! Electric coup! Self-driving on-demand vehicle service! A tunnel to Dodger Stadium! A flamethrower! The hyperloop! A $35,000 Model 3!

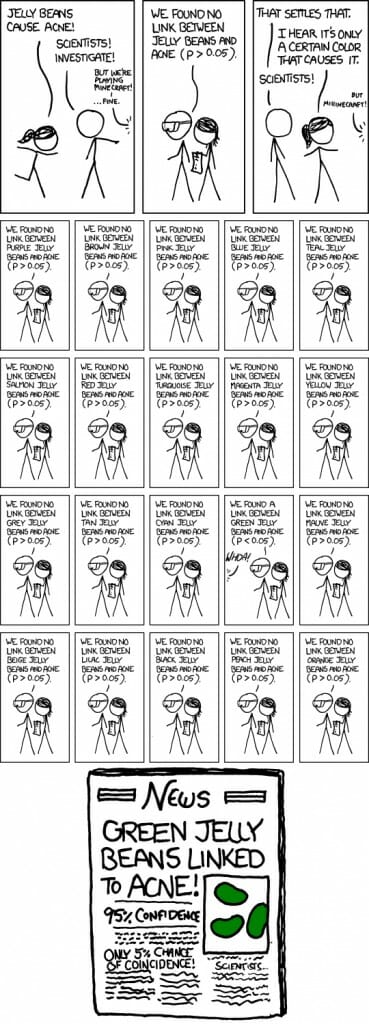

But beyond all this is the cultural divide between skeptics and passionate Tesla supporters. Tesla supporters online tend to have little or no financial knowledge or ability to analyze a company's balance sheets and operations, whereas the skeptics tend to be digging through details of balance sheets and pro formas. One might think this would be a red flag for Tesla supporters, but in fact it just hardens their position. All of us talking things like cash flow and quick ratios are just dinosaurs, captives of traditional narrow capitalist thinking -- exactly the sort of thing that the brilliant Elon is sweeping away. We are the ones who are naive at best, or at worst paid short-selling agents of the internal combustion engine lobby. I have never seen an investing situation like it, and the nearest analog I can come up with is the conflicts between Scientology supporters and skeptics.

So what exactly is the problem with Tesla? I will name a few of the major ones here, but want to note that much of the credit for the hard investigation and analysis on many of these points go to many folks in the $TSLAQ community, a group often huddled around @teslacharts on Twitter.

Problem #1: Tesla Has Tried to Disrupt Too Much

I have written about this before, when I said,

One of the hard parts about reinventing an industry is being correct as to what parts to throw out and what parts to keep. Musk, I think, didn't want to be captive to a lot of traditional auto industry thinking, something anyone who has spent any time at GM would sympathize with. But it turns out that in addition to all the obsolete assumptions and not-invented-here syndrome and resistance to change and static culture in the industry, there is also a lot of valuable accumulated knowledge about how to build a reliable car efficiently. In Tesla's attempt to disrupt the industry by throwing out all the former, it may have ignored too much of the latter, and now it is having a really hard time ramping up reliable, quality production.

Ditching the ICE, throwing out assumptions that PEV's had to be silly little econoboxes, and thinking about cars as a software platform are all awesome disruptions and fundamental to the Tesla competitive advantage. But at the same time Tesla was doing this, it also attempted to throw out 100 years of auto industry learning on manufacturing and selling cars. On the manufacturing end, Musk promised an "alien dreadnought" with machines that moved so fast humans wouldn't even be allowed in the building. Tesla has not been able to make this work, and as a result has had to try to relearn old rules of car manufacturing on the fly. This has hurt both their capacity ramp as well as their product quality.

On the sales end, Tesla wanted to do away with traditional dealers, and the Tesla owners I know loved not having to buy from a car salesman. But they did not come up with anything to replace the dealer system -- cars still need to be delivered, inventoried for sale, and repaired. All of these have been huge problems for Tesla in what Musk has called "delivery hell." Tesla has factory workers moonlighting delivering cars, it has inventory tucked away in all kinds of weird ad hoc lots, and Tesla owners often have to wait months for car repairs, usually because Tesla doesn't build enough spare parts.

Note that Tesla has also saddled itself with building out the entire world fueling network for the car. ICE car makers can depend on already existing gas station infrastructure. One could imagine that Tesla might have partnered with someone else to do this -- perhaps a large electric utility or a consortium of other car makers -- but instead has gone it alone building proprietary Supercharger stations across the country. Time will tell if this makes sense -- it could create a competitive moat protecting it from new competition but it also costs a LOT of capital and leaves them vulnerable to being the odd-man-out of some sort of shared network.

I will end this section by recalling the comparison of Tesla to Apple that so many of its supporters make. But as far as the iPhone is concerned, Apple is a design and software house. It does not build the phones, it has a partner do it for them. It does not write most of the applications, third parties do that. And (at least in the early days) it did not see through its own stores, it sold through 3rd parties. An Apple-like Tesla would NOT be trying to build its own manufacturing, service, and fueling capacity -- it would leverage its designs as its unique value-add and seek others to do these other lower-margin, capital-inensive tasks.

Problem #2: Tesla is Out of Capital (to Operate or Grow) And Seems Unable to Raise More

Tesla has never been profitable and continues to burn through a lot of cash. It burned through a couple of billion dollars in 2017 and more this year, and right now probably has less than $2 billion on hand with a lot of funding needs, including over a billion dollars of debt that is maturing over the next 6 months. Tesla may not have the cash even to cover its operating needs over the next 12 months, as Tesla has not been able to prove it can produce the model 3, or any of its vehicles, at a gross margin that will sustain the company's fixed costs.

But forget about operating losses for a moment -- you can go to twitter and argue these to death, and I will address it again below. But what of Tesla's growth? Tesla's current factory space is maxed out, so much so that they are building some Model 3's in a big tent. The Tesla growth story depends on the promised pickup truck and semi truck and coupe, but there is absolutely no place to build them right now -- a place to build them has not even been started and Tesla does not have the capital to create these assembly lines, or likely even to finish the product design. And even ignoring these, what about the next generation Model S and X? In the auto industry, car designs are typically refreshed as a minimum every 4-5 years. The Model S will be 5-years-old in December of this year. Where is the new second generation model? Tesla has enjoyed a 5-year head start on anything like comparable competitive vehicles. Now, a slew of challengers have been announced and will start appearing in dealerships in 2019 -- Tesla has perhaps 1 more year to buff up its product line before it has real competition.

Besides the car development and production issues, remember we also discussed that Tesla has chosen to build out its own fueling, new car distribution, and car servicing network. The current distribution issues and servicing complaints make clear that a LOT more capital is going to be needed in these areas. Capital is needed to inventory parts, to create dedicated storage and delivery centers, and to add more servicing capacity. Add to this Elon Musk's recent promise to bring body work on Teslas in house and thus create a whole body shop network, and that is a LOT of capital that Tesla does not have. It is clear to me (though maybe not to Tesla fans) that this capital is not going to come organically through large positive cash flows from operations.

Tesla really needed to raise $5 billion in early 2018. Its stock was riding high over $350 and its shareholders did not seem to care one bit about dilution. Why Tesla did not do a capital raise when the money was there and the cost of capital was so low is a total mystery to pretty much everyone. If nothing else, Elon Musk is absolutely obsessed with "burning the shorts" and the shorts all agree that the one thing that might hurt them in the short term and drag out their returns for years is a large capital raise. So why not?

One prominent theory among short-sellers and Tesla skeptics is that there is some sort of grand secret inside Tesla -- an investigation or a bad set of numbers or even some kind of accounting fraud -- that prevents Tesla from making the disclosures necessary to go to the capital markets. I am not sure this makes sense -- what secret could be so bad and still stay secret for so long? The fact that Tesla seems to hemorrhage senior accounting officers, finance VPs, and controllers just adds to the mystery. Whatever this mystery barrier to capital raises has been, it has only gotten worse with Tesla's recent SEC investigations and on-again-off-again settlements. No matter what, the result is that Tesla is starved of capital and apparently cannot easily get more.

If you buy or sell Tesla, this is essentially the question you are betting on -- Can Tesla raise capital? If they can't in the next 6 months, they are likely headed for bankruptcy or restructuring (but either way wiping out most of the equity holders). On the other hand, if they were to announce a multi-billion dollar capital raise tomorrow, the stock would rocket back in to the high 300's and all the shorts would be at least temporarily burned (though Tesla would still have long-term structural challenges). This is why it is inappropriate to have much more than a small piece of your portfolio either long or short Tesla -- you are effectively betting on whether this capital raise will happen and even the experts can't fathom it. I think it won't happen for the simple fact that if it could have happened, it should have already occurred, but I could be wrong.

Problem #3: Tesla is an Operational Mess and Not Good at Fulfilling Promises

Elon Musk makes a lot of promises, promises that get a lot of folks excited, but very few of these promises are ever met. In the long list of promises I listed right up at the top, very few if any have been fulfilled. For example, Tesla still is not anywhere near the production rates for the Model 3 that Musk promised it would reach over a year ago, a promise so clearly broken that Tesla is being sued over it. Musk claimed as many as a half-million pre-orders for the Model 3 mainly on Musk's promise to sell it for net $27,500 ($35,000 less the $7,500 federal tax subsidy). Now the $35,000 version is not even on the manufacturing plan (Tesla still can't figure out how to make money on it) and it certainly will never be produced before Tesla starts losing the $7500 subsidy after December.

For years Musk has pulled new product rabbits out of his hat every quarter, just when he needed them to complete financing or an acquisition. After the the stock pops up in response, little is ever heard of the suggested product again. The battery swap technology that got California to give Musk bigger subsidies has completely disappeared from the radar screen. Musk demonstrated what he said was a completed solar roof tile technology just in time to sell Tesla shareholders on the idea of bailing out SolarCity, but again the technology has never materialized and SolarCity has essentially been shutting down, with fewer new installations each quarter. The same was true of the Semi truck, released to great fanfare but totally MIA today. And beyond these promises are crazy, clearly inaccurate promises from Musk that they are taking all body shop work in house immediately or that they are producing their own auto carriers to alleviate a supposed auto carrier shortage. And even this does not include the small promises he has made almost every day to users to add this or that new feature. It is almost as if Musk has a psychological need never to admit that there is a problem for which he has not already implemented a solution.

Worse, the products Tesla is making are not fulfilling Tesla's early promise. Specifically, Tesla fan boards have been full of stories about delivery defects in new Model 3's, including parts that fall off and body panels painted the wrong color. Leaks from inside the factory have hinted at first-pass yields on the model 3 that are close to the worst in the entire auto industry. To try to keep investors happy, Tesla has promised that they would produce 5000, and later 6000 model 3's a week, but rather than achieve sustainable production at these levels the factory has engineered a couple of crazy push weeks where production is juiced to these levels, and then falls back to lower rates. This is probably one reason for the quality problems, and certainly is not a recipe for reducing production costs.

Problem #4: Q32018 May be Tesla's High Water Mark

Which brings us to the 3rd quarter results, which should be announced in just a few weeks. Musk has been vociferously promising for months that Q3 and Q4 would be GAAP profitable and cash flow positive. He went so far as calling out the Economist Magazine for having the temerity to suggest that this did not sound realistic.

Perhaps as a result of this very public commitment, Tesla has very clearly pulled out all the stops to really juice the third quarter. For example:

- It carried over a lot of inventory from Q2 to be sold in Q3

- It has mined its order book to find all the folks who have ordered the most profitable cars. It abandoned the promised first-come-first-served manufacture-to-demand approach to focus on batch producing cars for those who ordered the highest margin versions.

- It has mined two years of orders and sold them all in one quarter

- It has reportedly done a sale and leaseback of all its demonstration and loaner fleet

- It has reportedly taken full payment from multiple people for the same car, delivering it to one person and holding the money from the other for a 4Q delivery.

- It has stretched out the time it takes to repay deposits for cancelled orders to 45 days

- It has stretched its payment to vendors, resulting in a number of vendor complaints. As a result its net working capital has gotten more and more negative.

- It has had special end-of-quarter sales of inventory

- It has used expensive promotions (e.g. free Supercharging for life) that it promised earlier not to use again in order to move inventory at the end of quarter

- It has switched to batch production from produce to order in the factory, presumably to cut costs and increase throughput but having the effect of creating inventory for which there is no current buyer.

- Once it was too late for manufactured cars to get sold in the quarter, it cut way back on production in the last days to conserve cash.

- Tesla has some undisclosed number of government ZEV credits it can sell, which would lead to a one-time increase in profits and cash flow. Tesla takes advantage of a loophole in GAAP accounting to leave these off their balance sheet, presumably so they can act as Musk's personal burn-the-shorts slush fund.

It is not clear if this will result in a small profit or positive cash flow. The problem is that whatever Q3 results are, they will be almost impossible to duplicate in Q4. Tesla will likely talk about what a growth trajectory Q3 represents over previous quarters, and they will be right, but what will be missing from the story is how nothing will be left in the tank for Q4.

The following is essentially speculation, because Tesla refuses to answer any questions about their order backlog. In fact, Musk famously blew off an analyst in a previous conference call who tried to inquire about the order backlog. But there are good reasons to think that the backlog of profitable customer advance orders and deposits is tapped out, that Tesla in Q3 has serviced everyone in the backlog who wanted a car that could be produced at a reasonable gross margin and everyone else in the backlog are folks who ordered cars, particularly the $35,000 Model 3, that Tesla has no intention of building any time soon because they would lose their *ss doing so. In this context, Q3 is not an organic quarter in the midst of a growth trend but a manufactured quarter where over 2 years of pre-orders were tapped in one three month period, leaving nothing in the tank for the future.

The evidence for flattening demand for Tesla is pretty compelling. Model S and X sales volume has basically been flat for over a year. And as for Model 3, the unsold inventory tucked away in random locations combined with the desperation fire sales at the end of Q3 point to a saturation of demand.

Note that a flattening of demand has a double whammy for Tesla. First, it means that their stock valuation will likely crash. Tesla's valuation at huge multiples of revenue (there is no profit) only makes sense for a rapid growth company. If the rapid growth tails off, the valuation will come to Earth.

And this is not even the biggest problem. Let's take a step back. In the old days, say in the 1980's, growth was a consumer of cash. This is because manufacturing and inventory cycles were long. Growth meant investing in more parts and production now, only to get higher revenues later -- working capital skyrocketed with growth and could nearly bankrupt otherwise healthy growing companies.

Today, however, supply and manufacturing chains are much shorter. Products can be produced and sent to customers before the vendors are even paid. Dell computer was an innovator on this, getting paid by customers for a PC before Dell itself had paid for any of the parts. Combine this with Tesla's innovation of having customers put down deposits on their cars months or years before the sale, and this means that growth actually creates cash for Tesla as working capital becomes more negative.

I have the same thing happen in my seasonal business. Through the spring, as I hire people and visitation to our campgrounds increases into the summer, we get big increases in revenue immediately while we don't have to pay new hire salaries for a couple of weeks or expenses like trash for months. Growth generates cash because we get the revenue before we pay the expenses. But the whole thing reverses itself at the end of season, as revenues fall and all the bills come due. This negative cash flow effect as revenue growth reverses at the end of the operating season almost bankrupted me the first couple of years until I learned to plan for it.

In the same way Tesla has been getting positive cash flow (via negative working capital) from growth, but this will reverse the moment that growth slows. When their growth inevitably slows in the fourth quarter, no matter how well they claim to have performed in the third quarter, Tesla is going to see a huge cash crunch. I am not sure they will have the cash to cover it, and smarter people than I are betting on a Tesla bankruptcy or restructuring in the next 2-3 months. Any such event will largely wipe out equity holders. Which is why I am advising you to keep away. Elon Musk and Tesla may have some double-secret plan to avoid this cash crunch, but are you willing to bet your savings on it?

Problem #5: Elon Musk is NOT the Smartest Man on Earth

The ultimate answer to all these concerns about Tesla by Tesla fanboys is that they have confidence in Elon. I see people write on boards, dead seriously, that Elon is the smartest person in the world. One wrote two days ago that they thought he was the smartest guy in history. They have confidence that Elon will make things work out, and that Elon will always be able to attract new capital because everyone in the world feels the same love for Elon that they do.

Here is the problem: Elon Musk is not the smartest guy in the world. He is clearly a genius at marketing and brand building. He has a creative mind -- I have said before he would have been fabulous at coming up with each issue's cover story for Popular Mechanics. A mile-long freight blimp! Trains that run in underground vacuum tubes! A colony on Mars! But he suffers, I think, from the same lack of self-awareness many people develop when they are expert or successful in one thing -- they assume they will automatically be equally as brilliant and successful in other things. Musk creates fanciful ideas that are exciting and might work technically, but will never ever pencil out as profitable business (e.g. Boring company, Hyperloop). Musk is not good at managing operations or manufacturing. He does not seem like a very good planner, which should be a must in a business with long lead times and billions in capex. He has brought too much of the "fake it before you make it" culture from the web world, where the stakes attached to unsuccessfully faking it are so much lower than they are in, say, the car business. This natural tendency to overestimate one's abilities is just made worse by all the fan attention that constantly tells him he is the real Tony Stark and the Smartest Man on Earth.

SpaceX works pretty well because someone who is not-Musk and actually knows that business runs the operations and designs the product. Even in Tesla, the Model S was designed by someone else, as much as Musk would like to claim credit. I have said for over a year that Tesla needs to find the right role for Musk and it is NOT CEO and COO and CTO and chief Tweeting Officer all in one. Tesla needs Musk at this point as their face to the public. He would be a good chairman and could help lead the company's product road map. He is great at communicating exciting things to the public -- within limits.

The "within limits" proviso in the last line is based on what is surely Musk's worst flaw -- he can be a petulant, impulsive, unreliable child on Twitter. I won't go into all the stories, most of them made the national news, but he tried to insert himself into the Thai cave rescue story and when his contribution was not useful, called out one of the rescuers as a pedophile. He frequently is obsessed with short-sellers and taunts them with promises to burn them. He reacts poorly to criticism and bans a lot of critics on Twitter. And, most disastrously, he tweeted that he had funding secured for a $420 buyout of Tesla that caused the stock to shoot up, only to fall back to Earth when it was revealed that no such offer existed. This latter event was a clear violation of SEC rules, and after an SEC investigation Musk and Tesla settled with the SEC. But even that was not the end, as Musk then repudiated the settlement, and then two days later signed a new more onerous settlement, and then a few days after that mocked the SEC over twitter in a clear violation of the terms of the settlement he just signed. Which is where we sit today, waiting to see how the SEC responds to this latest outburst and with rumors swirling that other SEC and justice department investigations may be in progress at Tesla.

Which leads to the question -- is Musk just immature on Twitter, or is he actually corrupt ala Elizabeth Holmes at Theranos or the smartest guys in the room at Enron? People might respond that Musk is a brilliant, visionary guy -- he can't be corrupt! But my wife who has to have her blood tested a lot loved Elizabeth Holmes and her vision. I personally worked with Jeff Skilling briefly at McKinsey before he went to Enron and he was both visionary and a real genius. The way he introduces new products right when he needs an external boost, and then drops them, looks a lot like a stock-pumping operation. And I personally think the Tesla bailout of SolarCity was completely corrupt -- it benefitted Musk and his friends and family at SolarCity and did less than zero for Tesla shareholders.

* * *

That is the situation as I understand it. If you still want to make a big bet on Tesla, one way or other, hopefully you are a bit better informed of the risks. Trade carefully, as the saying goes. Or do as I do, and just watch the show because it is enthralling.