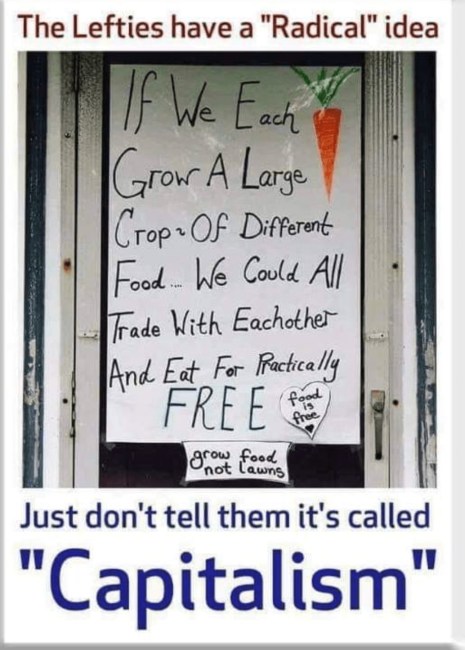

When I see stuff like this taken seriously, I know it is time to replace capitalism's marketing team

In the first part of this post I will discuss why this quote misses the heart of capitalism, and then I will come back to why this represents a level of historical ignorance that only a modern $200,000 college education could achieve.

The core of capitalism is cooperation

Virtually every task that human beings need to perform both to survive and to thrive (which I define as making one's life more fulfilling) requires both cooperation and coordination. For the smallest of survival tasks, like say a 5 person group stalking a mammoth, it is possible to imagine that cooperation can occur entirely among peers using direct communication.

At some point it does not take long for this loose cooperation approach to get complicated. Did everyone make their own spear? Did it make any sense for the best hunters to waste their time chiseling spearheads, or could there be one expert? If there is an expert, what share of the food would he get? What if everyone wanted to be the spear maker? What about that guy who always had some excuse not to go on the hunt with the team, should he still get food? If the lazy guy (called a free rider in economics) got food, why would anyone face the dangers of hunting?

One can see all these problems in the history of the communes formed in the 1960s and 1970s in the US. These communes were formed under a theory of pure cooperation, where the group would share all the labor as well as the product of the labor. Most of these communes broke down because participants had not realized just how much freaking work subsistence farming entailed and the group broke apart in rancor over the free rider problem (if you are getting a share of the food anyway, why work?).

As the goods or services produced get more complicated than subsistence hunting or farming -- ie if one wants things like vaccines or iphones -- then the cooperation problem gets harder because it requires the cooperation of people who may never even meet face-to-face or be able to communicate with the whole group to coordinate actions. How do those of us in the Eastern Mediterranean felling giant cedar trees know how much wood the folks on the Upper Nile need, and when? Such coordination is easy in a hunting team of four people, who know each other and their skills and can divvy up roles in an attack by just talking to each other directly. But it becomes exponentially harder as the production task gets more complex.

These problems of coordination and cooperation have been solved throughout history just two ways: By voluntary action driven by prices and profit or by bosses (called chief, king, premier, Caeser, fuhrer, etc) using force.

Emergent behavior in a boss-free society is for people to voluntarily trade their products or labor to others for what they need -- this is the simple core of what we call capitalism. This is not a system imposed on people, but the natural state into which free people evolve. The hunting party gladly trades part of the catch to the best spear-maker whose efforts make them more successful and increase the time they can focus on hunting. Folks who can't or won't hunt must find other ways to be valuable to the group to get a share of the food. Some inevitably innovate, discovering new food sources or hunting approaches. As production and transactions get more complex, people move from barter to money, with prices for goods and services single-handedly performing the coordination function in a completely distributed and emergent manner (see I Pencil).

Capitalism is the only approach in all of history to solving the cooperation and coordination problem without the use or threat of force (though beware than many have availed themselves of force while still inaccurately calling it capitalism -- another example of poor brand control by the marketers of capitalism). Capitalism is the un-system, the default emergent behavior of rational self-interested humans allowed to transact freely. Every other system is founded on force under the auspices of a Boss. It does not matter how the boss was selected (or self-selected) or if they work through some council or bureaucracy, the Boss is ultimately forcing the cooperation and performing the coordination. He (and it has almost always been a he) decides who is making the spears, who is going on the hunting party, and who gets how much of the catch. If you don't want to be the spear maker, tough sh*t you probably aren't getting any food.

And you may soon find that the boss gets a special triple helping of all the food and that any female who denies the boss her sexual favors will soon see their family starving. Feudal, fascist, royal, and communist bosses all shared in common that they were exponentially wealthier than their citizens and in most cases effectively the wealthiest person in their country with the most and best of everything. Capitalist countries tend to be the exception, with elected leaders at best making upper middle class salaries (at least from legitimate public sources).

As production gets more complex, the boss model gets worse and worse because it not just hard, but impossible for any central authority to solve the coordination problem On the funny end of this is the Soviet Union producing in one year, say, a million pencil erasers but only 100 pencils. On the horrible and tediously repetitious side of this is the tens of millions of people who died in Mao's Great Leap Forward. Happy-clappy modern Ivy League socialists will argue that this is just socialism done wrong, that well-intentioned people would never end up with this sort of outcome. But it never works out that way. In part because the folks leading these Marxist efforts are not as well-intentioned as they pretend, but even more so because super nice people who create a system where leaders have power over life and death (as must be the case in a socialist economy) are eventually displaced by the Hitlers and Stalins and Maos and Pol Pots. Ho Chi Minh seemed to begin as a smart, well-intentioned guy, but Lê Duẩn who took power from him was a brutal dictator who impoverished the Vietnamese people.

Unfortunately, over time, even nominally capitalist countries like the United States seem to devolve to the force end of the scale**. As markets become larger and more complicated, helpful rules emerge for the markets and transactions -- being emergent does not necessarily mean it is without structure. However, when these rules get adopted or coopted by governments, the rules can be modified in a messy political process to create abuses and corruption. More and more force enters the equation, eg we will arrest you if try to sell your wine out of state or try to build too many housing units on your plot of land. A surprising number of the defects in capitalism often cited by its detractors result from these flawed government rules, and not from capitalism itself. Michael Moore's "Capitalism A Love Story" turns out to be almost 100% an indictment of government interventions in the market to favor certain cronies, rather than of true free markets (yet more poor brand control for those marketers of capitalism).

So if one wants pure cooperation in a voluntary system without the use of force, capitalism is the one and only choice. But what about all this stuff about competition? Through sh*tty marketing, capitalism is often portrayed as fundamentally about competition rather than cooperation, and occasionally competition is even fetishized by certain defenders of capitalism who seem about a half step away from Spencerian social Darwinism. The role of competition in markets is not to cull the weak -- in fact, Ricardo showed 200 years ago that with free markets, even the weakest producers still can contribute to the group's well-being. The reason that competition exists, and the benefits that flow from competition, are based on the fact that almost all resources (land, iron ore, oil, and most importantly human time) are scarce.

Back to our hunting example, the obsidian from spear points might be extremely expensive for a tribe, requiring a lot of trade goods sent to far away tribes. So imagine that there is one person who uses twice as much obsidian to make a spear point than another person, Everyone in the group is better off if the spear-making job goes to the more productive person. The wasteful guy needs to go find something else to do. And that is the heart of competition right there -- achieving efficiency in a way that makes everyone richer. By the way, I can easily picture this same situation in the Boss-force model where the wasteful spear-maker is the Boss's brother (or other crony) and keeps the job to the detriment of the whole tribe but increased wealth for the Boss's family. Only the use of government force in markets allows this sort of crony outcome.

Historical Ignorance of Fetishizing Primitive Societies

A few thoughts about the realism of fantasy quoted above, because this is already too long

- The subsistence food production likely employed by any of the societies the author above is pining for is WAY more work than any modern American could imagine

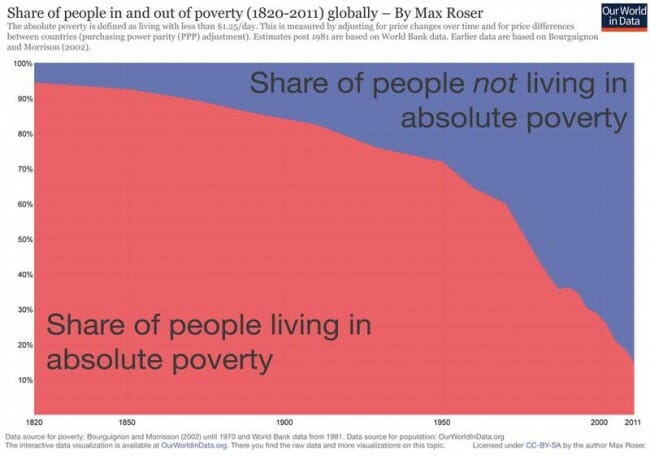

- These societies were POOR, which is why unproductive members were frequently left to die. It was a poverty so extreme it is almost beyond our modern Western imagining.

- Life would have been horribly uncomfortable -- no heating, no cooling, constant fleas and lice, slow travel

- Life would have been intellectually impoverished. You would never have experienced any land, any people, any climate more than a few hundred miles (at most!) from your birthplace. There were no writers or artists or intellectuals because everyone who could work had to work.

- Life would have been short. The smallest cut could get infected and kill you. You would be a ready host for any virus or bacteria that came along. You would watch many or most of your kids die young.

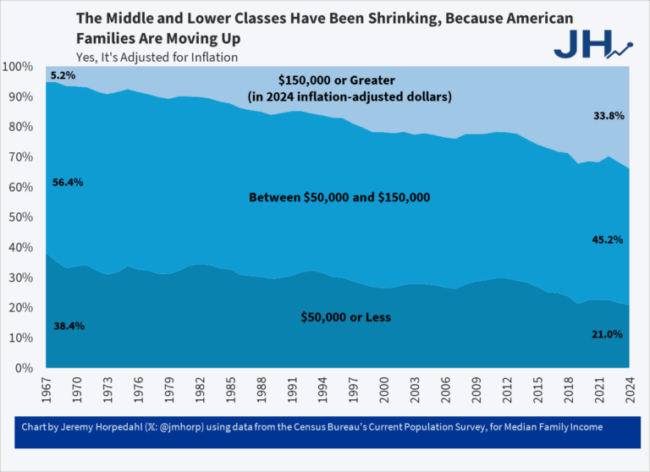

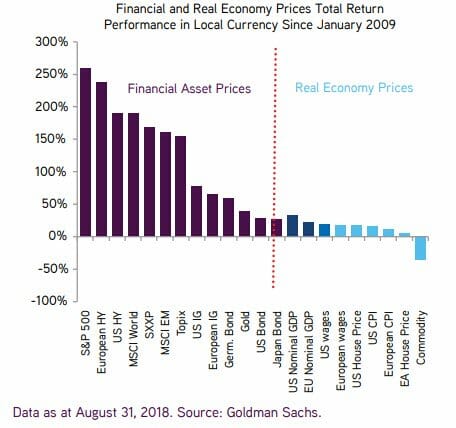

There is no happy, cooperative, simple, small-scale life that also has leisure time, iphones, blogging jobs, or vaccines. Capitalism is the exception in history, because it is the only way we have become rich and long-lived. Most intellectual advancement is all traceable to capitalism -- the Renaissance occurred when it did due to proto forms of capitalism that created wealth in private hands that allowed for people to be, say, full-time painters. Remember that the "victims" or losers in capitalist competition, the 10th percentile poorest people in the US, are still well-off enough to be counted among the very rich in many countries outside the first world.

I will end with this meme:

**Postscript: There is a parallel to this in communist countries, as countries like China and Vietnam exited from communist impoverishment to some economic improvement by allowing more openness to markets and private profit.