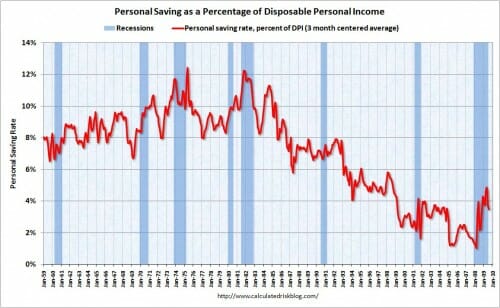

On any number of occasions from October through February, I predicted that this recession would top out at perhaps 9% unemployment at the most, and would probably not be as bad as the recession of the early 1980's. My logic was that we had a mortgage-driven banking crisis, but that the crisis was perhaps not as bad as that of the late 1980's and that many fundamentals (e.g. interest rates) were looking way better in this recession than in the early 1980's. I honestly thought that Bush and Obama Treasury and Fed officials were declaring the sky was falling more from the danger to their beloved former employers on Wall Street than due to any economic fundamentals.

Well, obviously I was wrong. Unemployment has topped 10% and could be headed higher.

So the question is, do I accept that others saw something I did not, or do I crack open the self-serving excuses. Well, at the danger that this will fall into the latter category (I will leave that to readers to decide) I do think some things have changed since late last year that have contributed to worsening the economy.

Businesses are reluctant to invest when the returns on their investment are wildly unpredictable, particularly when future income changes are more driven by changing acts of Congress rather than fluctuations in the market. Over the last year the Congress and Administration have:

- Printed trillions of dollars of new money, raising the risk of future inflation

- Borrowed trillions of dollars, sucking capital out of private lending markets

- Run up deficits that pretty much guarantee future tax increases

- Toyed with health care bills that will substantially increase the cost of labor

- Toyed with climate bills that will substantially increase the cost of fuel and electricity

- Demagogued industries with average to below-average profitability for making obscene profits that must be reduced (e.g. health insurance companies who make 3-4% of sales)

- Taken over whole industries (autos, banks) and run them to the benefit of favored political constituencies, even when it violates the law (e.g. trashing for secured creditors of auto companies in favor of the UAW).

- Demonstrated a disdain for money-making by imposing populist compensation limits on executives of out-of-favor companies and industries.

- Spent money in the stimulus mainly to add government jobs, every one of which is generally focused on making my life running a business harder. If you do not understand or believe this, you have not run a business that employs people.

- Shown a general philosophic hostility towards markets and capitalism

I am sure this is just a subset (Louis Woodhill has more in this vein here), but these all have negative effects on investment. My company for one has backed out of several planned expansions this winter for four reasons:

- Half of my costs are labor, and I don't know how much Congress is going to increase my labor costs. Current health care bills will increase it at least 8% -- given that my typical margin in 5-8% of sales, a government action that increases half my costs by 8% is worrisome. Worse, my smaller competitors will not bear this expense under certain versions of the legislation.

- My second highest expense is fuel and electricity. I have no idea right now how much Congress may raise these expenses.

- Capital for small businesses is gone. I can get secured equipment financing, but that is it.

- Assuming I make any money from these investments, I have no idea how much I will be able to keep. I would not be surprised at all if Obama pushes my marginal rates over 50% -- and investments in my business are just too much work and risk to keep less than half if I make any money.

I used to work as for several years in St. Louis as VP of Planning for Emerson Electric. I worked for a guy named Chuck Knight, who could be a real pain in the *ss to work for, but was a) brilliant and b) always willing to speak his mind without the typical filters a lot of other executives apply. It appears that his successor Dave Farr, who I also knew at Emerson, is following in this tradition:

Emerson Electric Co. Chief Executive Officer David Farr said the U.S. government is hurting manufacturers with regulation and taxes and his company will continue to focus on growth overseas."Washington is doing everything in their manpower, capability, to destroy U.S. manufacturing," Farr said today in Chicago at a Baird Industrial Outlook conference. "Cap and trade, medical reform, labor rules."...

Companies will create jobs in India and China, "places where people want the products and where the governments welcome you to actually do something," Farr said.

The unemployment rate in the U.S. jumped to 10.2 percent in October, the highest level since 1983. Emerson, which Farr said employs about 125,000 people worldwide, has eliminated more than 20,000 jobs since the end of 2008 to lower expenses.

"What do you think I am going to do?" Farr asked. "I'm not going to hire anybody in the United States. I'm moving. They are doing everything possible to destroy jobs."

Politicians in both parties are generally clueless about this kind of thing, because very few of them have ever run a business or even even been in a real business position other than as lawyer or lobbyist. Just look at how George McGovern feels now that he has run a business.

But the Obama administration is almost scary clueless. In defending their promotion of a good business environment, they cite the most hostile item on their agenda:

"This administration has made a significant commitment to U.S. manufacturing, including reforming the country's health insurance system to bring down costs and make American companies more competitive globally," Griffis said.

Not. One. Single. Clue.

Actually, I think the Obama administration may believe this, which just accentuates their preference for a corporate state wherein "business friendly" means support for the top 20-30 corporations in the country. In the context of a few old-line corporations with politically powerful unions, health care reform is helpful in that it dumps a bunch of the corporation's commitments to present and past workers onto the taxpayers. But these are not the companies that grow the economy -- they are just the ones with out-sized power in political elections.