What Is Wrong With Health Care, Though My Diagnosis is Opposite of the Left's

Note: I did not like the way I first wrote this post so I have re-written it extensively.

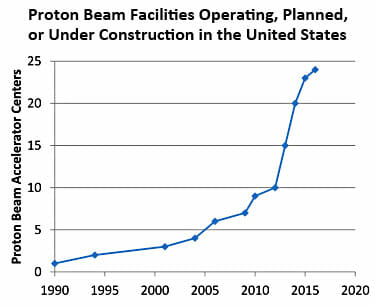

Progressives are passing around this chart from Brookings as an indicator of "what is wrong" with the US healthcare system.

This is how Kevin Drum interprets the chart:

In other words, the supposed advantage of PRT—that it targets cancers more precisely and has fewer toxic side effects—doesn't seem to be true. It might be better in certain very specialized cases, but not for garden variety prostate cancer.

And yet, new facilities are being constructed at a breakneck pace. Why? Because if they build them, patients will come. "They're simply done to generate profits," says health care advisor Ezekiel Emanuel. Roger that.

This is an analysis that may be true, but let's take a moment to consider how strange it is. Forget health care for a minute. Think about any other industry. Here is what they are effectively saying:

- Industry competitors are making huge investments in a technology that has no consumer value

- The competitors in this industry are all making investments in this technology so rapidly that the industry is exponentially over-saturating with capacity.

And from these two facts they conclude that the profits of industry competitors will increase??

Let's for a moment say this is true -- an enormous investment that has no customer utility and that is made by so many players that the market is quickly over-saturated actually increases industry profits. Let's take a moment to recognize that this is BIZARRE. We have to be suspicious of some structural issue for something so bizarre to happen. As is typical of progressives, their diagnosis seems to be that private actors are somehow at fault for being bad people to make these investments. But these same private actors, even if they wanted to, could never make this work in any other industry, and besides there is no evidence that hospital managers are any worse people than, say, cookie company managers. The problem is that we have fashioned a bizarre system through heavy government intervention that apparently makes these pointless investments sensible to otherwise rational actors.

One problem is that in any normal industry, consumers would simply refuse to buy, or at least refuse to pay a very high price, for services that have little or no value. But in health care, we have completely eliminated any consumer visibility to prices. Worse, we have eliminated any incentive for them to care about prices or really even the utility of a given procedure. This proton beam thingie might improve my outcomes 1%? Why not, it's not costing me anything. Perhaps the biggest problem in health care is that the consumer has no incentive to shop. Obamacare does nothing to fix this issue, and in fact if anything is taking us further away from consumer shopping and price transparency by working to kill high deductible health insurance and HSA's.

There is only one other industry I can think of where capital investment, even stupid capital investment, automatically translates to more profits, and that is the regulated utility business. And that is what hospitals have become -- regulated utilities that get nearly automatic returns on investment.

In a truly free market, if these investments made no sense, one would expect very soon a reckoning as those who made these nutty investments go bankrupt. But they obviously don't expect this. They expect that even if it turns out to be a bad investment, they will use their political ties to get these costs built into their rate base (essentially built into reimbursement rates). If any private or public entity refuses to pay, you just run around screaming to the media that they want to deny old people care and let sick people die. Further, the government can't let large hospitals go bankrupt because it has already artificially limited their supply through certificate of need processes in most parts of the country.

The Left has proposed to fix this by creating the IPAB, a group so divorced from accountability that it can theoretically make unpopular care rationing decisions and survive the political fallout. But the cost of this approach is enormous, as it essentially creates an un-elected dictatorship for 1/7 of the economy. Which tends to be awesome if your interests and preferences line up with those of the dictator, but sucks for everyone else. Which category do you expect to be in? (Oh, and let's not forget how many examples we have from history of benevolent technocratic dictatorships - zero.)

The much more reasonable solution, of course, is to handle these issues the same way we do in cookies and virtually every other product -- let consumers make price-value tradeoffs with their own money.

Your comparison of proton beam facilities to cookie factories doesn't work, because the reimbursement for proton beam services does not follow supply and demand curves. Most patients with cancer are elderly and on Medicare. Medicare has fixed reimbursements for disease-therapy combinations. At present, the reimbursements for proton beam therapy are high because the devices were rare, the capital costs were high, and operating costs were high. All those elements will be less costly with increased production and increased experience. However, Medicare reimbursement will remain the same for years until some government cost-cutters realize that they're overpaying. (This happened with lots of expensive new technologies such as MRI and laparoscopic surgery.) Also, many health insurance companies base their reimbursements on Medicare's fee schedule. Therefore, private sector reimbursements for proton beam therapies will be no more responsive to supply and demand curves than Medicare.

I suspect if we looked at the production of televisions in the 1950s and computer production in the 1980s, we might see a similar upward trend. Profit seeking is what makes luxury items accessible to the common man. Every major appliance we have in the majority of homes today, whether it's washer/dryer, hot water heater, furnace, dish washer, microwave, TV, etc. at one point was only accessible to a very small minority that were willing to spend relatively large sums of money on something uncommon but useful. As more producers saw the opportunity for profit, and sought to undercut the existing producers, the prices of these items fell, along with the high profits, until we have the market for these items that exists today, where I can pick one up at any of half a dozen stores all within about 5 minutes of each other.

Where the breakdown happens is when new producers are not allowed to enter the market to lower the initially high profit margins, or when the customers have no incentive to prioritize cost and look for products with a lower cost.

What is your disagreement with Warren???You seem to be saying that the free market doesn't work because the government spends money irrationally - while Warren's argument is that neither the government nor patients who are insulated from costs spend money rationally.

When I have similar conversations with my liberal friends (constrasting healthcare with other industries), the argument isn't that we have made healthcare unlike other industries in the free market, but rather healthcare, by its nature, doesn't (and couldn't possibly) operate like a free market. When you get in a car accident, you don't have an opportunity to shop around for the best value on having your spleen removed. Yes, they always assume the worst possible examples, but I have yet to figure out a way to overcome this rebuttal and I would love to hear your thoughts.

there is a very direct parallel here with lasik.

when it first came out, it was expensive, then, the industry dramatically over invested, prices plummeted, and a lot of the later entrants lost money. but it was all great for consumers.

Car accidents are covered by car insurance not health insurance. Tell them cancer is a much better example because it isn't simply wrong.

In fact, those worst possible cases are the best arguments for reshaping health insurance into an actual insurance: Hedging against unforeseen catastrophic events. Cancer and other catastrophic illnesses are rare enough that, even though they're tremendously expensive to treat, 100% coverage insurance against _just them_ would be very affordable. Probably cheaper than car insurance.

Health insurance as we have it now is misnamed, it's a medical care prepayment plan. What would happen to the price of car insurance if it paid for your gas? Sure, your gas budget would fall, but your insurance budget would increase to meet it. The same happens with medical insurance covering routine things like doctor's visits and elective procedures.

This isn't a panacea, but it could help. Another issue preventing prices from adjusting even if consumers do start price shopping: The licensing requirements for even basic medical services put very tight constraints on supply, ensuring relatively high prices. Coyote's Dr. in a Box example isn't really bad, you can go to a less well trained practitioner for an initial diagnosis. As long as they are competent to handle simple stuff (colds, flus, strains, sprains, etc) and identify potentially serious and time sensitive stuff (appendicitis, skin cancer, menengitis) for referral, you're going to end up better off on average. They won't catch everything (but neither does an MD) and a lot of their care might be "Take two of these and call a Dr. in the morning if it doesn't clear up." But again, that's what a lot of MDs do, and MDs would be have more time available for real problems if they had someone to triage the minor stuff for them.

The market for medical care is an entire ecosystem unto itself. A whole lot has to change before it can be made better, and it's likely that one change for the better can lead to a net negative effect. Unfortunately, there is no simple fix. Another problem is peoples' perceived ignorance when making medical decisions. Getting more and more expensive tests isn't costless for consumers, almost everyone has copays and even 10% of thousands of dollars adds up. But they take their doctor's word that they need the tests, and (for many reasons) doctors are very risk averse and recommend procedures well beyond the point of diminishing returns where the value of the test is far lower than its cost.

Well, there are catastrophic and non-catastrophic events. For the former, you buy insurance, because you know you won't be able to get coverage once the catastrophe occurs. The free market for fire insurance on your home works perfectly well, so why shouldn't the free market for insurance against catastrophic medical events? At most, the proper role for government is subsidizing people if they can't afford it.

For non-catastrophic events, however, there is plenty of time to shop. You could easily look around for the best price on having your teeth cleaned, your eyes examined, a routine checkup, health maintenance drugs, etc. For these things, which involve about 3/4ths of all medical expenditures, there is no need for insurance, and a prepaid medical plan (to be distinguished from insurance in the proper, catastrophe-protection, sense of the word) only discourages price discovery. People can see the obvious value of fire insurance, but very few people think it is a good value to have a prepaid home-repair plan to "insure" against clogged drains, leaky roofs, etc.

So the free market handles catastrophic and non-catastrophic events in different ways. Now, if some people can't afford to pay for non-catastrophic medical expenses, I suppose we can look at government subsidies in that area too. But forcing everyone to have a prepaid medical plan for non-catastrophic events, which is what 3/4ths of Obamacare essentially amounts to, suppresses the free market in an area where it is perfectly capable of functioning, and in which many if not most people would do just as well with no "insurance" at all.

Only after writing my reply did I notice that someone else had already replied. And funny thing, he makes the same distinction between genuine insurance for catastrophes and prepaid maintenance plans for non-catastrophes. I guess the point is obvious -- at least to everyone but the designers of Obamacare.

This problem is one of the arguments raised in Overtreated. Shannon Brownlee argues that if you look in different regions of the country, you find wildly different amounts of medical facilities, but no matter what facilities you see, they are always running at capacity. You might five five times as many MRI machines in one state as another, but in both states the machines have a full queue of patients. It looks like doctors identify more people as "needing" an MRI when there is a higher supply of MRI machines.

I find it a compelling argument that there is no bright line for what kind of treatment is "necessary". That's an additional blow against the IPAB strategy. It's not just a question of whether one treatment works better than another. It's much fuzzier when you get into diagnostics, and it's worse still when you consider that people with one serious ailment quite frequently have at least one more as well.

On the solution side of your discussion, it's a point worth repeating that trading these things on more of a market would do quite a lot to solve the oversupply problem. Solutions based on supply and demand have proven to be very effective in the real world, so long as the people on each side of the transaction actually feel the price that is involved.

"...an enormous investment that has no customer utility..."

Real Estate in China anyone?

http://www.news.com.au/business/china-building-mega-cities-but-they-remain-empty-sparking-fears-of-housing-bubble-burst/story-e6frfm1i-1226611169281

"Health insurance as we have it now is misnamed, it's a medical care prepayment plan"

Great insight.

Wish it were mine, but I stole it from more than a couple places. Including this blog, iirc.

Prices in our health care system are essentially the allocation of fixed investment cost across a spectrum of payers. There are only two ways to reduce health care costs. First, the European/single payer way. Reduce fixed costs. Fewer hospital beds, less technology, less effective drugs. This causes wait times for procedures and less effective health care results and more pain.

The second way, which can only marginally reduce costs, is to improve the efficiency of the delivery of health care costs. Most of this process would be the streamlining of Medicare and Medicaid programs. The problem is that the Democrats have no interest in improving hte efficiency of these programs, mainly because the most feasible way is to create market based programs like Medicare Advantage which gives consumers choice and was essentially outlawed in ObamaCare. Republicans cannot offer any such reforms because if they did the Democrats would demagogue the issue very effectively (this is the political system we have).

Lasik is a terrible comparison, because it is: a) elective; b) relatively simple; c) a net driver of costs. Ezra Klein talked about this a while back:

"First, Lasik is a refusable good. It isn't like a heart bypass. Second, don't compare the trends of one good to [o]ne sector. It isn't necessarily the case that individual treatments -- bypasses, for instance -- aren't getting better and cheaper as time goes on, just like Lasik. But they're developing more and more stuff they can do to us, and we're getting sicker, and so overall costs are going up.

"To put this another way, spending on laser eye surgery is way higher than it was 30 years ago. But individual laser eye surgeries are improving and becoming cheaper. That makes it seem like Lasik is a model for the system, but Lasik is really a model for a good. if health-care spending increased as much as eye surgery spending, the country would be bankrupt already."

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/discussion/2010/02/10/DI2010021003012.html

Your reply starts with a bad axiom in the first sentence. The cost of health care is not (not even inflation- or population-adjusted) a fixed investment. In a system with reasonable incentives, the investment required to provide health care would be coming down with time, the amount of return for the dollar spent would increase, just like your cell phones.

Take morganovich's example, above. Before there was lasik eye surgery, there was radial karatomy. A surgeon with awesomely steady hands would cut radial slits partway through your cornea, let your eye bulge out a bit, and correct your vision. $20,000 an eye, and more risky, too.

Some clever bloke said, 'Hey, I can come up with a newfangled laser machine to do it cheaper'. Invests a LOT of money into a machine to map your eye and ablate the surface, in and out, 15 minutes for both eyes. [Had it, loved it, but now losing my close-up vision] He could process through more people, in less time, less physician skill involved. Lasik was cheaper than RK, and so it took over the market. That is how it is supposed to work.

But, if you are in a field where the gov't hides all pricing from you, he could have priced lasik at 2X the cost, and if people chose it because they 'heard' it was better, then why not? Heck, the doctor probably gets more money selling the pricier alternative. He'd be *stupid* to ignore the fact that one treatment rewarded him with more money.

Efficiency has very little to do with it. The problem is, with all the costs hidden, there is no incentive to provide better health care for less money, so we get worse health care for more money. The rest is just decoration.

"It looks like doctors identify more people as "needing" an MRI when there is a higher supply of MRI machines."

In at least a couple of states, thanks to investigations, it's been shown that referrals for MRIs have been based either upon kickbacks from imaging facilities to doctors, or on doctors having direct financial interests in imaging facilities. If you're going to take the approach that price transparency addresses this issue, then you also have to expand the remit to include full disclosure of interests. Is it workable to expect that patients not only run price comparisons on procedures, but financial background checks to see whether their doctor makes additional money out of them? Should doctors not only have their diplomas framed on their walls, but itemized financial statements showing any investments or contracts with other providers?

a) Elective, yes, and therefore priced competitively.

b) Simple, yes, compared to the radial keratomy that preceded it. That is why it took over the market.

c) A net driver of costs. FALSE:

c1) Spending on laser eye surgery is keratomy is maybe 1000x higher than it was 30 years ago, because at that time Lasik was used in 10 vison centers across the country for 1 year. It was only patented in 1989. You could also say cell phones are a million times more common than they were 30 years ago, that still doesn't mean they have bankrupted us. Ezra Klein is guilty of bad maths.

c2) I had Lasik eye surgery 12 years ago, back when it cost $4400. I have spent exactly zero dollars on contact lenses, cleaning solution, eye exams, and backup glasses in that time. I don't have any records from before, but feel that I broke even on costs around the 6-8 year mark. At today's rates of $1200/two eyes, the payback should be even faster.

Paragraph 12 of the linked article is factually correct but functionally wrong. Paragraph 11 is misleading: see Heart Surgery in India for $1,583 Costs $106,385 in U.S.. The assumption that the costs cannot come down is a result of the system of hidden prices and results. If the one bit of the article I am expert on contains so little truth, I assume the rest of the article is factual garbage.

Your reply demonstrates you have zero clue of what you are talking about. Your example is the best way of demonstrating why fixed investment costs are the primary driver of health care costs. With "LASIK" surgery, and almost every economic event, there are two types of costs: fixed and variable. WIth this procedure and almost every other, it is very obvious that the variable portion of the costs are minimal: there usually is an assistant and the doctor, and the entire procedure takes about 10 minutes, a few eye drops. Of the $2,000 or so the procedure costs, the variable part of the cost is probably about 10% of the charge, if that.

The primary driver, instead, is the massive investment the practice had to make in the technology to create the capacity to provide such services. This investment and its associated costs are experienced no matter how many procedures are done. If more procedures the average fixed costs are lower and fewer procedure the higher.

WHich leads us to the two ways to cut health care costs: either lower the number of LASIK machines available or increase the efficiency of utilization of those machines. WIth LASIK surgery, the primary driver in lowered cost was the latter. THe surgery became more reliable and more routine so more and more people decided to do the procedure, meaning that the fixed cost per procedure was drastically reduced.

"The Internets" tell me that a Lasik excimer laser costs between $200,000 and $500,000 in year 2000. That is a large investment, but over ten years, probably not a large fraction of the costs. The original post is arguing that there is no incentive to reduce these fixed installation costs, if you get paid basically more money for using more expensive equipment.

And that is how it currently works: medicare reimburses $2800 for a chest cat scan, $180 for a chest x-ray. These reimbursements are fixed. If your hospital profit is the same percentage-wise, and the note is not proportionally greater on the cat-scan machine, then why _not_ buy one for your 25-bed hospital?

I might be missing your point. You state that the fixed costs are the primary driver of health costs. Your statement is true, but I am arguing that the reason fixed costs are primary is the incentive system driving huge purchases. In a more competitive system, there would be less fixed cost investment ... except for cases like Lasik, where there was a real improvement in outcomes. [cf. MRI scans done in ER broken bone in extremity complaints]

So, exactly. You completely agree with me. The only way to reduce health care costs is to reduce the fixed capital investment: fewer hospital beds, fewer advanced machines, less investment in drug R&D. But you also get what you pay for. Lower capital investment means less effective health care.

But you are trying to make a different argument.

I am not making any arguments AGAINST your claim as to the "incentive system" for higher and higher fixed cost investment, although I think your reasoning is somewhat simplistic and not complete. Certainly investors of capital in health care want the highest rate of return and that Medicare "reimburses" a higher rate for the more advanced procedures (chest CAT scan vs. X-Ray). But, the issue is not as simple. AGAIN, this is a matter of allocating the fixed costs. A high end hospital/clinic is going to have a CAT scan, MRI, and other advanced imaging technology. They may "overuse" these technologies and "overcharge" Medicare for them because a chest x-ray could have been just as diagnostically efficient. But, the cost of the CAT scan is sunk. It is the same if they do 1 procedure or 1000 procedures. The $2800 cost you cite above for a chest CAT scan is just the allocation of the fixed investment and overhead costs to a "fixed" payer. The only way you can "SAVE" money is to forgo having the advaned technology.

Further, the incentive system is not the only issue driving these investments. Consumer demand is a major part of it. Americans expect our doctors to use the best equipment, etc. Some of that is as you state because prices are hidden. If the consumer had to pay directly for these procedures they might choose the lower cost in many cases. But in health care consumers are extraordinarily risk adverse, particularly for their dependents (and pets in veterinary medicine). They want the best treatment because they do not want to take risks, even if the "return on investment" of their spending decision is rather negative.

Second, another issue driving the "incentive system" is the malpractice culture in our country. The doctors making the diagnosis and doing the procedures in our tort system are responsible for ALL risk. Therefore, they have to make sure that as much risk is eliminated as possible. So, using your example of the chest CAT scan, doing that procedure may only improve your diagnosis 1%, but you are exposed to severe punitive penalties if you do not cover this 1% risk. So, you do the procedure even though it is not "medically warranted".

I like both of your explanations at the end of your post, I don't even know that they are arguments. I just don't understand why you think "consumer demand" or "malpractice culture" are unchangeable axioms.

In particular, your reference to veterinary clinics is great. SOME people spend thousands of dollars on their pets, even as the prices are specifically listed upfront. But other people choose not to, when confronted by the price of extreme medical care. Veterinarians sure have a hassle-free, cash-upfront business compared to my wife (a pediatrician), but I don't think anyone foresees vet expenses becoming a rising burden on our society. People want heroic measure performed on their human loved ones, precisely because they don't see/bear the costs.

But that can be changed. It can be changed easier than medical advances are usually made.

[I would argue your statement that reduced medical capital costs lead to less effective medical care. It does not work like that in cell phones, in computers, in any other business not distorted by government spending and regulations. Even cars ... you are arguably getting a better value than you paid for, 50 years ago, when adjusted for inflation. Better gas mileage, better comfort, more gadgets, hugely better crash survivability. And that IS an industry strangled by government regulations. A backup camera in every car, by 2014, for the children? I bet you the number of child injuries go down less than 10%, as people ignore the camera screens when the novelty wears off. /rant]

And, again, you are just choosing another argument.

Clearly, I think that some changes can be made. That is why I brought up tort reform. THey are changeable but the net result of these "changes" would be to reduce the level of capital investment in health care. Tort reform and changing the financial payment patterns would "reduce" cost by reducing this level of future investment. The CAT scan would be used 100 times instead of 1000 times which means that the "charge" for the CAT scan would be around 10 times higher less the "haircut" the current investor would have to take on the return on his capital investment. The ultimate impact on this is that investment in current and newer technology would be slowed. This would reduce overall cost.

Next, to counter the "don't see/bear the cost" argument and how it impacts consumer demand, I "in reality" agree with you. But, on the other hand, I would argue that the average consumer does not see it that way. Almost everyone would claim that either they paid their insurance premiums and/or they paid their Medicare taxes. Therefore, they are entitled to the highest quality care POSSIBLE. Even the futile, but heroic, end of life medical costs are something that the average person believes is their right. Think about this from the perspective of emergency medical care. The consumers of this country EXPECT to have full emergency care 24/7. That means that each of these facilities needs to be equipped at all times to handle all possible medical emergencies. That is why emergency medical care is so much more expensive than routine. The CAPACITY exists. The only way to reduce this medical cost is to reduce capacity. (Note: That is why routine procedures are charged so much when it is sought in emergency care, they are allocating the fixed cost of this capacity across even routine procedures. So even if we reduced how some of the poor, uninsured patients get care the "costs" of emergency medicine are still mostly the same and just have to get allocated across different procedures).

And, to address your last argument, I think you are completely out to lunch on it for the most part. Your arguments about cell phones etc is completely missing the point, but can be extended to make the medical argument for me. Sure, cell phones costs have been reduced. But, how effective would a cell phone be without the billions of dollars of infrastructure that have been made across the globe? This is not a "You did not build that argument", but the value of the cell phone would be much more limited. The same is true with medical care. If you reduced the capital investment you reduce the capacity of the system. Fewer and less effective drugs. Fewer and less effecitive diagnostics. Fewer and less effective options.

To this point, I have not argued if we are spending enough or too little. Clearly, on the margin I believe that we can make small impacts by changing our tort system (I am sure your pediatrician wife would agree) and in the ways that consumers see prices for medical costs. But the real change is in teh massive capital investments that we make, particualarly in pharmaceuticals and high end technology. I think that we get what we pay for in the United States and they get what they pay for in Europe and Canada.

The single biggest issue I have regarding the complaining by pundits about the build out of Proton Beam Therapy buildings is that they have the balls to think that they know the market. That's right, if the Soviets just had these enlightened folks in charge making production decisions, they'd still be around. They are among the elite few blessed with uncommon DNA and just _know_ these facilities aren't needed.

I walk past one of these new facilities most every day. It and another PBT facility at another campus is being built as a result of the single largest one time donation to the Mayo. This mans voluntary gift not only _hughely_ reduces the costs of the facility - something none of these enlightened few seem to ever acknowledge, btw - but it changes the very nature. One man is sharing his wealth to help other people. Even if it is an insignificant marginal improvement, it's not happening merely because people they're just spending other people's money.

I'm throwing this out there since while the overall system set up has huge flaws, we need to keep in mind that specific things may actually make sense. Personally, I have a hard time seeing these institutions putting money into building these things at the very time insurance companies are pulling back unless they really think there's a market for them. And remember, once they're built there is little marginal costs to running them 24/7 to treat all sorts of things. The prostate cancer treatment gets all the press because it's controversial. But there are a couple handfuls of other cancers where this is the best form of treatment.

Third way: US Gov provide either interest free loans or equipment to hospitals and clinics that serve XX people and commit to XX% of procedures to people who meet some low income criteria, and maybe have a set profit margin for associated procedures.

Research equipment grants are common, and have a generally more restricted or lower benefit.

I don't want the US government making such decisions. How is some bureaucrat in Washington DC going to know what the capital investment needs are for some county in Oregon (pick your own state if you wish)? How will they determine if the subsidy is a legitimate need or not? When politics is involved in "interest free loans" then it is the people with the political connections, not the best utilization of capital, that get these loans. How can the government determine what the appropriate "profit margin" is for a procedure given the vast expanse of the United States and its different demographics?

I want the government OUT of health care decisions, not more involved.

The gov would not make health care decisions, the hospital/clinic would make a proposal for specific equipment with the proposal describing how it would be used. If the proposal fails the hospital/clinic could still make the purchase based on a business decision.

So, you believe that the government should just rubber stamp any and all health care proposals then? If a hospitcal clinic seeks one of your no interest loans they should just do it? If they say no (which you counter that the hospitcal can just make their own private investment), isn't that "making a health care decision"??? I think it is. Why let the government be the arbitrator of where an MRI investment goes or not goes? What happens then is that politically connected areas get an over investment in health care capital and areas without political connections are undercapitalized. This is why governments are NOT good allocators of precious investment capital. They do not make decisions based on real economic need, but POLICITAL need. If the president needs a state in the coming election.......lots of political favors.

The capital market is by far the best allocation method of capital. It may not be perfect because capital investment is done seeking future returns under uncertainty. But it is still the best and should be the only way.

A "proposal" is a request. "Denied" is an answer. Not rubber stamp. Roads and research. Are you just throwing mud at the wall to see what sticks? I have a similar irrational reaction to having the government in health care, and I see lots of reasons why this is a bad idea, but I think it's a worse idea to have the capital costs of a medical machine be a (note: not the only) main driver for diagnosis.

But a denial or acceptance is a decision. I think I very clearly laid out why I oppose government making decisions on health care capital investment. YOU GET MISALLOCATION BASED ON POLITICAL CONSIDERATION. THIS IS DONE IN EVERY CAPITAL DECISION MADE BY THE GOVERNMENT. Look at West Virginia and how Robert Byrd somehow got disproportianete investment there. Sorry, your idea is just a bad.

I watched some leftomentary on healthcare and the conclusion was to spend less by underpaying doctors and buying cheaper MRI equipment. This reminds me of that. I used to joke that half the spending is on people with 6 months to live and the other half is spent on imaging, so if we didn't x-ray dying people everything would be free.