Believe it or not, I am not going to update on the CRU emails. The insights into the science process are illuminating, and confirm much that we have suspected, but faults in transparency do not automatically win the game -- they lead to [hopefully] future transparency which then allows for better criticism and/or replication of the work.

My frustration today is a recent article in Scientific American [with the lofty academic title "Seven Answers to Climate Contrarian Nonsense"] which purports to shoot down the seven key skeptics arguments. Many others have shown how the author does not do a very good job of shooting down these seven, but that is not my main frustration. The problem is that, like many of the global warming myth buster articles like this, the author completely fails to address the best, core arguments of skeptics, preferring to snipe around at easier prey at the margins.

In this post, I discuss his article and suggest 7 better propositions alarmists should, but never do, address.

You can see discussion of all of these in my recent lecture, on video here.

Don't have 90 minutes? Richard Lindzen of MIT has a great summary in the WSJ that mirrors a lot of what I delve into in my video.

Here are my seven alternative skeptics' claims I would like to see addressed:

Claim A: Nearly every scientist, skeptic and alarmist alike, agree that the first order warming from CO2 is small. Catastrophic forecasts that demand immediate government action are based on a second theory that the climate temperature system is dominated by positive feedback. There is little understanding of these feedbacks, at least in their net effect, and no basis for assuming feedbacks in a long-term stable system are strongly net positive. As a note, the claim is that the net feedbacks are not positive, so demonstration of single one-off positive feedbacks, like ice albedo, are not sufficient to disprove this claim. In particular, the role of the water cycle and cloud formation are very much in dispute.

Claim B: At no point have climate scientists ever reconciled the claims of the dendroclimatologists like Michael Mann that world temperatures were incredibly stable for thousands of years before man burned fossil fuels with the claim that the climate system is driven by very high net positive feedbacks. There is nothing in the feedback assumptions that applies uniquely to CO2 forcing, so these feedbacks, if they exist today, should have existed in the past and almost certainly have made temperatures highly variable, if not unstable.

Claim C: On its face, the climate model assumptions (including high positive feedbacks) of substantial warming from small changes in CO2 are inconsistent with relatively modest past warming. Scientists use what is essentially an arbitrary plug variable to handle this, assuming anthropogenic aerosols have historically masked what would be higher past warming levels. The arbitrariness of the plug is obvious given that most models include a cooling effect of aerosols in direct proportion to their warming effect from CO2, two phenomenon that should not be linked in nature, but are linked if modelers are trying to force their climate models to balance. Further, since aerosols are short lived and only cover about 10% of the globe's surface in any volume, nearly heroic levels of cooling effects must be assumed, since it takes 10C of cooling from the 10% area of effect to get 1C cooling in the global averages.

Claim D: The key issue is the effect of CO2 vs. other effects in the complex climate system. We know CO2 causes some warming in a lab, but how much on the real earth? The main evidence climate scientists have is that their climate models are unable to replicate the warming from 1975-1998 without the use of man-made CO2 -- in other words, they claim their models are unable to replicate the warming with natural factors alone. But these models are not anywhere near good enough to be relied on for this conclusion, particularly since they admittedly leave out any number of natural factors, such as ocean cycles and longer term cycles like the one that drove the little ice age, and admit to not understanding many others, such as cloud formation.

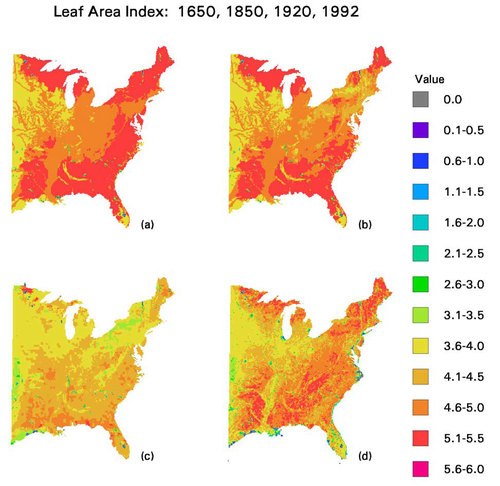

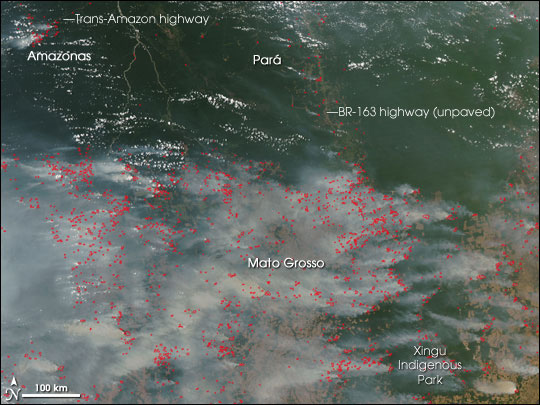

Claim E: There are multiple alternate explanations for the 1975-1998 warming other than manmade CO2. All likely contributed (along with CO2) but it there is no evidence to give most of the blame to Co2. Other factors include ocean cycles (this corresponded to a PDO warm phase), the sun (this corresponded to the most intense period of the sun in the last 100 years), mankind's land use changes (driving both urban heating effects as well as rural changes with alterations in land use), and a continuing recovery from the Little Ice Age, perhaps the coldest period in the last 5000 years.

Claim F: Climate scientists claim that the .4-.5C warming from 1975-1998 cannot have been caused natural variations. This has never been reconciled with the fact that the 0.6C warming from 1910 to 1940 was almost certainly due mostly to natural forces. Also, the claim that natural forcings could not have caused a 0.2C per decade warming in the 80's and 90's cannot be reconciled with the the current claimed natural "masking" of anthropogenic warming that must be on the order of 0.2C per decade.

Claim G: Climate scientists are embarrassing themselves in the use of the word "climate change." First, the only mechanism ever expressed for CO2 to change climate is via warming. If there is no warming, then CO2 can't be causing climate change by any mechanism anyone has ever suggested. So saying that "climate change is accelerating" (just Google it) when warming has stopped is disingenuous, and a false marketing effort to try to keep the alarm ringing. Second, the attempts by scientists who should know better to identify weather events at the tails of the normal distribution and claim that these are evidence of a shift in the mean of the distribution is ridiculous. There are no long term US trends in droughts or wet weather, nor in global cyclonic activity, nor in US tornadoes. But every drought, hurricane, flood, or tornado is cited as evidence of accelerating climate change (see my ppt slide deck for the data). This is absurd.