The NY Times has somehow decided that one of America's real problems is widening income distribution, or more specifically, the exponentially increasing wealth of the top tenth of one percent of US earners. The series seems to be running to about 47 episodes (actually 10), but a key article is here, entitled "Richest Are Leaving Even the Rich Far Behind," There are a number of ways to attack this article. One is to fisk their really abused and misused numbers, which George Reisman does here on the Mises Economics Blog.

Lets accept that the very very rich are getting richer. So lets move from there to the question of...

"so what?"

The Times is a little weak on the "so what". I presume that in their intellectual-statist readership, it is an axiom that rich people suck and rich people getting richer sucks more. However, it is possible to pull out four things the Times extended editorial-masquerading-as-a-news-story finds bad about increasing income inequality:

- As the rich get richer, there is less money left for the rest of us

- The process of the rich getting richer reduces opportunities for the rest of us

- Having very rich people around make the rest of us feel bad

- The rich are only getting richer because the rest of us are subsidizing them through tax policy

It has been a while since I have really gotten carried away writing about a topic (at least three or four days) so I will now proceed to address each of these in turn and in some detail.

As the rich get richer, there is less money left for the rest of us. At the end of the day - this is what is in most people's minds when they decry aggregations of wealth. There are many, many people in the world, even in this country, who think of wealth as a fixed pie, as a zero sum game where one person's victory requires another persons loss.

If we were living in 17th century France, where the rich nobility got that way by taxing the crap out of the working peasantry, this would probably be an adequate view of reality. Wealth came from the land and its products, whose supply, given no technology improvements for decades, were both relatively fixed. This zero sum view of commerce led to a mercantilist view of the world economy, where it was thought that wealth was fixed, and that the only thing that could be done to it was to move it around, or tax it, or steal it, or loot it.

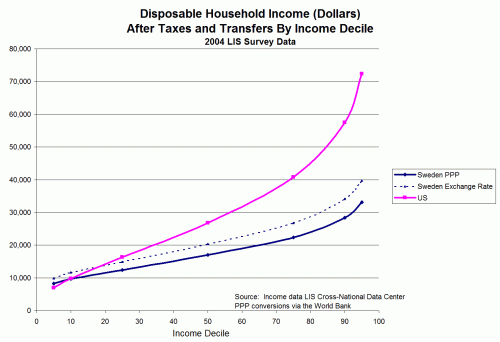

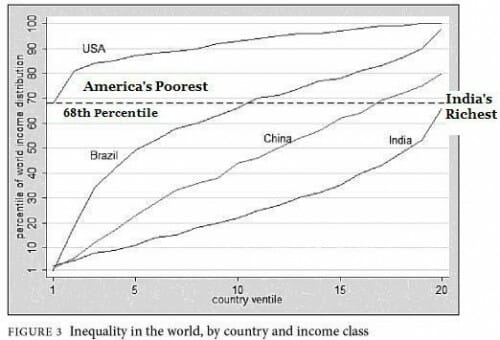

But we don't live in 17th century France. We live in a modern, dynamic capitalist society where wealth is created. One proof of this is so obvious that it amazes me anyone clings to the implicit zero sum economy assumption: Compare the US in 2000 to the US in 1900. We are so much wealthier top to bottom in our society than in 1900 its not even worth spending much time on the proof. This is not just in real dollar terms, but in things that affect ones life, from average life span to leisure time to entertainment to technology. People who live in the poorest 20 percentile today have things -- such as a lifespan over 70, access to cancer cures, cars, computers, VCRs -- that not even the richest one half of one percent had in 1900. The poorest 20 percentile in this country would be the upper middle class or even the rich in many countries of the world today.

Michael Dell and Bill Gates are both in that evil 1/10 of 1% of richest people. But how did they get that way? They made their fortunes by providing me with this incredible tool on my desk that was unimaginable when I was born 40+ years ago, but now is pedestrian. Right now I am typing on a Dell computer using Microsoft Windows, which I bought from the suppliers for a mutually agreeable price in a totally uncoerced manner. My computer provides me with thousands of dollars of value - in productivity, in entertainment, in the ability to do new things that could never be done before (e.g. blog). Most of this value I keep for myself; some, about $1200 in this case, went to the suppliers of labor and materials to build and program this thing. And a small portion, less than $100, went towards the fortunes of Mr. Dell and Mr. Gates who had the vision to build the businesses they did. The PC I have creates new value all around: Thousands of dollars of new value for me the user and hundreds of dollars in the form of jobs and new markets for suppliers. Mr. Dell and Mr. Gates keep just a small portion of all that value created. At some level, they are working cheap. And any one of us, had we had the vision, could have piggy-backed on Mr Gate's or Mr. Dell's wealth creation by buying stock in their firms.

The process of the rich getting richer reduces opportunities for the rest of us. Since the "zero sum" argument is so easy to disprove, proponents of rich=bad have morphed their argument to this one. This accusation comes up several times in the NY Times series, but is hard to refute mainly because the authors never explain the mechanism that they think is at work here or show any shred of proof. The articles cite folks such as Warren Buffett, George Soros, and Ted Turner. But how has their fortune-making reduced my personal opportunities one iota?

Do I have less opportunity because Warren Buffet has made good investing decisions? Heck, one can argue that any American has always had the opportunity to gain wealth in direct proportion to Buffet at any time, merely by buying Berkshire Hathaway stock.

How about Ted Turner. Do I have less opportunities to improve myself because Ted Turner got rich creating CNN? I guess I could facetiosly argue that by his creating CNN, others can no longer create a 24-hour cable news service because he has locked up the market, but Fox has disproved even this narrow argument.

What about George Soros? I guess you could argue that from time to time my Sony Walkman was a buck or two more or less expensive because of some currency game he was playing in the markets, but I don't see how my opportunity has been reduced. A better argument is that Soros's being wealthy might really threaten my opportunity if only because he funds so many statist-socialist causes with his billions.

In fact, this is one of those black-is-white arguments. The reality is exactly the opposite. When most rich people get rich (with the exception maybe of Peter Angelos and other tort lawyers) they do so by creating new value and thereby opportunity. While all these folks may be really wealthy, in reality the wealth they have amassed is but a small percentage of the wealth and value that they created. Where did the rest go? To all of us, of course, in the form of jobs, and tools, and longer lifespans, and better entertainment.

Having very rich people around make the rest of us feel bad. OK, this sounds like a problem for group therapy, but you see it in print all the time. The disparity of incomes is "troubling" and could lead to "resentment". If one were living in Venezuela or Nigeria or some country where, like 17th century France, wealth came from looting rather than the free exchange of goods, then I would agree that the income disparity would be troubling. Shoot, if people were much wealthier than I because they were using the legal system to loot the rest of us, I would be pissed off (ironically, this is the case with the billionaire tort lawyers, but this is the last group that the Times will ever challenge).

However, in this country, where most of the very rich got that way through hard work and better ideas, the result of free and uncoerced commerce, why be resentful? Sure, I would love to have a G-V aircraft and hot Swedish wife [ed note: oops, my wife might read this] like Tiger Woods, but lacking these, I have zero desire to deny them to Tiger. I don't even begrudge super-tramp Paris Hilton her millions (but she did inspire me to change my will so my kids don't inherit from me until they are well past their majority). Heck, I have spent whole vacations touring the discarded toys of the super-rich (e.g. mansions in Newport, RI). What fun would there be without a moving target to aspire to?

So why do the Times and some many intellectualls legitimize this envy? This type of envy has driven anti-semitism and in fact all sorts of racism through the ages.

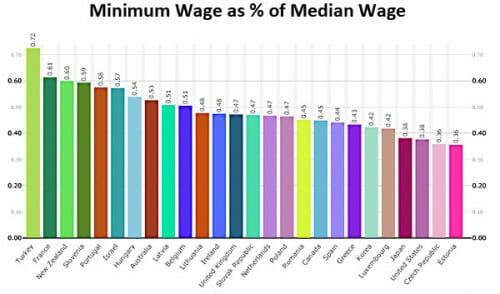

The rich are only getting richer because the rest of us are subsidizing them through tax policy. Around my house, I joke that everything, at least in my family's opinion, turns out to be my fault. The equivilent at the NY Times is that everything is Bush's fault, and in particular, the fault of Bush's tax cuts. The Mises article cited above does a pretty good job of fisking the argument that the tax system post-cuts favors the rich. I took on took this notion here and here. The Times "analysis" makes two major mistakes:

- Social Security Tax hide and seek: The NY Times article shows the very wealthy paying lower marginal rates than lower level earners. As I pointed out here, this is entirely because they are including social security taxes in their analysis and that the taxes are capped at $90,000. If you look at only income taxes, then marginal rates do not drop at higher incomes.

The left's argument here is highly contradictory. When wanting to make the "rich are not paying enough" argument, they include Social Security taxes, knowing that since those taxes are regressive, they make it look like the rich are somehow getting off easy. However, when discussing Social Security, the don't want to think of them as taxes - because they want Social Security to be insurance with premiums rather than a transfer program with taxes.

- Bracket Creep: The TImes points out that the income tax rate for the super rich is no higher than the rate for the merely rich or even $100,000 earners. The implication is that the super rich are somehow getting a better deal. But in fact, the problem is that the definition of rich, vis a vis taxes, has been lowered through the years. The whole history of the income tax is to sell a tax as applying only to the very very rich, and then broadening the applicability over time. The federal income tax followed this path, as has the AMT. More recently, the top rate on California income taxes is seeing the same creep. The statist trick is to apply a rate to the super rich, then creep it down so eventually it applies to everyone. Then, they cry that - hey, the super rich aren't paying more than the middle class, so they institute a new higher super rich rate. Rinse and repeat.

Conclusion. I will leave you with the lyrics from Rush's The Trees:

There is unrest in the forest

There is trouble with the trees

For the maples want more sunlight

And the oaks ignore their pleas

The trouble with the maples

(and they're quite convinced they're right)

They say the oaks are just too lofty

And they grab up all the light

But the oaks can't help their feelings

If they like the way they're made

And they wonder why the maples

Can't be happy in their shade?

There is trouble in the forest

And the creatures all have fled

As the maples scream `oppression!`

And the oaks, just shake their heads

So the maples formed a union

And demanded equal rights

'the oaks are just too greedy

We will make them give us light'

Now there's no more oak oppression

For they passed a noble law

And the trees are all kept equal

By hatchet,

Axe,

And saw ...

Update: Several people said I missed the point about mobility, rather than just the rich getting richer. I respond to this here.