A Government Healthcare Alternative

A few years ago I began to find the hard-core libertarian anarcho-capitalist advocacy to be getting sterile. I would sit in some local discussion groups and the things we would argue about were so far outside of reality or what was realistically politically possible that they seemed pointless to talk about. Taking a simplified example, baseball purists can argue all day the designated hitter rule should go away but it is never going to happen (players support it because it creates another starting roster spot and owners like it because it juices offensive numbers which drive ratings). So I embarked on suggesting some left-right compromise positions on certain issues.

One result was my proposed climate compromise, which fit the classic definition of a good compromise (both sides don't like it) as many skeptics disowned me for writing it and the environmental Left campaigned hard against a similar proposal in Washington State.

I tried something similar with a proposal for restructuring the government role in health care. First, I defined what I think are the two most important problems a government health care proposal has to address. Most current and proposed plans fail to address at least one of these:

The first is a problem largely of the government's own creation, that incentives (non-tax-ability of health care benefits) and programs (e.g. Medicare) have been created for first dollar third-party payment of medical expenses. This growth of third-party payment has eliminated the incentives for consumers to shop and make tradeoffs for health care purchases, the very activities that impose price and quality discipline on most other markets.

The second problem that likely dominates everyone's fears is getting a bankrupting medical expense whose costs are multiples of one's income, and having that care be either uninsured or leading to cancellation of one's insurance or future years.

I think the second point is key. Everyone keeps talking about a goal of having coverage -- coverage even if you don't have money or don't have pre-existing conditions. But that is not, I think, the real human need here. The real need is to be protected from catastrophe, a personal health-care crisis so expensive it might bankrupt you, or even worse, might deny you the ability to get the full range of life-saving care. Everything else in the health care debate and rolled up in Obamacare is secondary to this need. Sure there are many other "asks" out there for things people would like to have or wish they had or might kind of like to have, but satisfy this need and the majority of Americans will be satisfied.

And so I proposed this:

So my suggestion ... was to scrap whatever we are doing now and have the government pay all medical expenses over 10% of one's income. Anything under that was the individual's responsibility, though some sort of tax-advantaged health savings account would be a logical adjunct program.

I found out later that Megan McArdle, who knows way more about health care policy than I, has been suggestion something similar.

How would a similar program work for health care? The government would pick up 100 percent of the tab for health care over a certain percentage of adjusted gross income—the number would have to be negotiated through the political process, but I have suggested between 15 and 20 percent. There could be special treatment for people living at or near the poverty line, and for people who have medical bills that exceed the set percentage of their income for five years in a row, so that the poor and people with chronic illness are not disadvantaged by the system.

In exchange, we would get rid of the tax deduction for employer-sponsored health insurance, and all the other government health insurance programs, with the exception of the military’s system, which for obvious reasons does need to be run by the government. People would be free to insure the gap if they wanted, and such insurance would be relatively cheap, because the insurers would see their losses strictly limited. Or people could choose to save money in a tax-deductible health savings account to cover the eventual likelihood of a serious medical problem.

A few weeks ago I started reading the blog from the Niskanen Center after my friend Brink Lindsey moved there from Cato. If I understand him, Niskanen has quickly become a home to many libertarian-ish folks who focus on real workable, executable policy proposals more than maintaining libertarian purity. In that blog, Ed Dolan has proposed something he calls UCC (Universal Catastrophic Coverage) which would work very similarly to what I proposed earlier:

Universal catastrophic coverage is not meant to cover every healthcare need of every citizen. Instead, UCC would offer protection from those relatively rare but ruinous healthcare expenses that are truly unaffordable. (Note: As we use the term UCC here, it is not to be confused with the more narrowly defined catastrophic insurance that is available, in limited circumstances, under the ACA.)

Here is how UCC might work, as outlined in National Affairs by Kip Hagopian and Dana Goldman. Their version of the policy would scale each family’s deductible according to household income. The exact parameters would be subject to negotiation, but to use some simplified numbers, the deductible might be set equal to 10 percent of the amount by which a household’s income exceeds the Medicaid eligibility level, now about $40,000 for a family of four. Under that formula, a middle-class family earning $85,000 a year would face a deductible of $4,500 per family member, perhaps capped at twice that amount for households of more than two people. Following the same formula, the deductible for a household with $1 million of income would be $96,000.

The cost of the catastrophic policy would be covered by the government, either directly or through a refundable tax credit. The policies themselves could, as in the Swiss model, be offered by private insurers, subject to clear standards for pricing and coverage. Alternatively, they could take the form of a public option, for example, the right to buy into a high-deductible version of Medicare.

With UCC in place, people could choose among several ways to meet their out-of-pocket costs, which, for middle-class families, would be comparable to those of policies now offered on the ACA exchanges.

One alternative would be to buy supplemental insurance to cover all or part of expenses up to the UCC deductible. The premiums for such supplemental coverage would be far lower than policies now sold on the ACA exchanges, since the UCC policy would set a ceiling on claims for which the insurer would be responsible. If the supplemental policies included modest deductibles or co-pays of their own, they would be more affordable still. Although UCC itself would be a federal program, the supplemental insurance market would continue to be regulated by the states to meet their particular needs.

Very likely, many middle-class families would forego supplemental insurance and cover all of their routine health care costs from their regular household budgets, the way they now pay for repairs to their homes or cars. Doing so would be easier still if they took advantage of tax-deductible health savings accounts—a mechanism that is already on the books, and could be expanded as part of reform legislation.

The main thing that has always flummoxed me is that I have no idea how expensive this plan might be. Dolan is claiming it could be done at reasonable cost.

As it turns out, the numbers don’t look all that bad. Because UCC leaves responsibility for routine care with individual families, in line with their ability to pay, it would be far less expensive than a system that offered first-dollar coverage to everyone. Hagopian and Goldman estimate that their version of UCC would cost less than half as much as the projected costs of the ACA.

The impact on the federal budget would be further moderated if the tax deduction for employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) were phased out as UCC came online. Tax expenditures for ESI currently cost the budget an estimated $235 billion per year, an

Employing People in California Really is Harder

California is a uniquely difficult place for companies trying to actually employ people rather than robots. Owning a business in that state, you could be forgiven that the legislation actually embarked on a program to explicitly punish companies for hiring people. The state has spent the last ten or twenty years defining a myriad of micro offenses employees for which may sue employers and make large recoveries -- everything from having to work through lunch to having the wrong chair and not getting to sit in that chair at the right times of day.

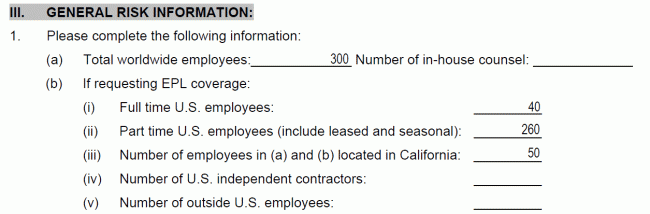

To illustrate this, I want to show you the insurance application I just received. Most companies have something called employment practices liability insurance. This insurance helps pay legal and some settlement expenses if and (nowadays) when a company is sued by an employee for things like discrimination or harassment or any of the variety of sue-your-boss offenses California has established. In that multi-page application, after the opening section about name and address, the very first risk-related question asks this:

They specifically ask about your California employment, and no other state, in order to evaluate your risk.

The other insurance-related result of California's regulatory enviroment is that if one is in California, it is almost impossible to get an employee practices insurance deductible under $25,000. This turns out to be just about exactly the amount of legal costs it takes to get a nuisance suit filed with no real grounding dismissed. It essentially means that any disgruntled ex-employee, particularly one in a protected class, can point their finger at a company without any evidence whatsoever and cost that company about $25,000 in legal expenses. Rising minimum wages is not the only reason MacDonald's is investing so much in robotics.

More NCAA Discrimination Against Athletes With Stupid Amateurism Rules

When I was a senior at Princeton, Brooke Shields was a freshman. At the time of her matriculation, she was already a highly paid professional model and actress (Blue Lagoon). No one ever suggested that she not be allowed to participate in the amateur Princeton Triangle Club shows because she was already a professional.

When I was a sophomore at Princeton, I used to sit in my small dining hall (the now-defunct Madison Society) and listen to a guy named Stanley Jordan play guitar in a really odd way. Jordan was already a professional musician (a few years after he graduated he would release an album that was #1 on the jazz charts for nearly a year). Despite the fact that Jordan was a professional and already earned a lot of money from his music, no one ever suggested that he not be allowed to participate in a number of amateur Princeton music groups and shows.

My daughter is an art major at a school called Art Center in Pasadena (where she upsets my preconceived notions of art school by working way harder than I did in college). She and many, if not most of her fellow students have sold their art for money already, but no one as ever suggested that they not be allowed to participate in school art shows and competitions.

A football player for the University of Central Florida has lost his place in the team, and hence his scholarship, due to his YouTube channel. UCF kicker Donald De La Haye runs "Deestroying," which has over 90,000 subscribers and has amassed 5 million views, thus far. It's not the channel itself that cost him his scholarship, though -- it's the fact that he has athletics-related videos on a monetized account.

The NCAA saw his videos as a direct violation to its rule that prohibits student athletes from using their status to earn money. UCF's athletics department negotiated with the association, since De La Haye sends the money he earns from YouTube to his family in Costa Rica. The association gave him two choices: he can keep the account monetized, but he has to stop referencing his status as a student athlete and move the videos wherein he does. Or, he has to stop monetizing his account altogether. Since De La Haye chose not to accept either option, he has been declared inelegible to play in any NCAA-sanctioned competition, effectively ending his college football career.

When I was a sophomore at Princeton, my sister was a Freshman. We were sitting in my dorm the first week of school, watching US Open tennis as we were big tennis fans at the time. My sister told me that she still had not heard from her fourth roommate yet, which was sort of odd. About that time, the semifinals of the US Open were just beginning and would feature an upstart named Andrea Leand. My sister says, hey -- that's the name of my roommate. And so it was. Andrea was a professional tennis player, just like Brook Shields was already a professional actress and Stanley Jordan was already a professional musician. But unlike these others, Andrea was not allowed to pursue her talent at Princeton.

I don't know if student athletes should be paid by the school or not. We can leave that aside as a separate question. People of great talent attend universities and almost all of them -- with the exception of athletes -- are allowed to monetize that talent at the same time they are using it on campus. Athletes should have the same ability.

Postscript: I wrote about this years ago in Forbes. As I wrote there:

The whole amateur ideal is just a tired holdover from the British aristocracy, the blue-blooded notion that a true "gentleman" did not actually work for a living but sponged off the local [populace] while perfecting his golf or polo game. These ideas permeated British universities like Oxford and Cambridge, which in turn served as the model for many US colleges. Even the Olympics, though, finally gave up the stupid distinction of amateur status years ago, allowing the best athletes to compete whether or not someone has ever paid them for anything.

In fact, were we to try to impose this same notion of "amateurism" in any other part of society, or even any other corner of University life, it would be considered absurd. Do we make an amateur distinction with engineers? Economists? Poets?...

In fact, of all the activities on campus, the only one a student cannot pursue while simultaneously getting paid is athletics. I am sure that it is just coincidence that athletics happens to be, by orders of magnitude, far more lucrative to universities than all the other student activities combined.

My Open Question to Progressives Is Still Open

A while back I asked progressives:

Taking the government's current size and tax base as a given, is there a segment of the progressive community that gets uncomfortable with the proportion of these resources that are channeled into government employee hands rather than into actual services for the public?

No response to date. This is not a rhetorical question. I am honestly curious if progressives worry about the percentage of government budgets that go to government workers, or if there is a progressive argument for this (despite the fact that it seems to be starving the actual programs progressives support).

I was reminded of this when I read this article from Steven Greenhut: (hat tip maggies farm and their links roundup)

Municipal governments exist to provide essential services, such as law enforcement, firefighting, parks and recreation, street repairs and programs for the poor and homeless. But as pension, health-care and other compensation costs soar for workers and retirees alike, local governments are struggling to fulfill these basic functions.

There's even a term to describe that situation. "Service insolvency" is when localities have enough money to pay their bills, but not enough left over to provide adequate public service. These governments are not insolvent per se, but there's little they can afford beyond paying the salaries and benefits of their workers.

As a city manager quoted in a newspaper article once quipped, California cities have become pension providers that offer a few public services on the side. It's a sad state of affairs when local governments exist to do little more than pay the people who work for them.

Not surprisingly, the union-dominated California state legislature has been of little help to local officials dealing with such fiscal troubles. The state pension systems have run up unfunded liabilities, or debts, ranging from $374 billion to $1 trillion (depending on the financial assumptions one makes). But legislators have ignored meaningful pension reform. This has forced local governments to cut back services or raise taxes to meet their ever-increasing payments to California's pension funds.

It's one thing to ignore the plight of hard-pressed cities and counties, but now legislators are trying to make the problem a lot worse. Assembly Bill 1250 would essentially stop county governments from outsourcing personal services (financial, economic, accounting, engineering, legal, etc.), which is a prime way counties make ends meet these days.

The Progressive Left Becomes State Rights Advocates. Who'd Have Thought?

Many libertarians like state's rights because it creates 50 different tax and regulator regimes, and libertarians assume that people and businesses will flow to the most free states. However, California progressives have discovered they like state's rights as well, though they are in more of the antebellum South Carolina category of desiring state's rights in order to be less free than the Federal government allows.

After a bid to launch a California secession movement failed in April, a more moderate ballot measure has been approved, and its backers now have 180 days to attain nearly 600,000 signatures in order to put it up to vote in the 2018 election.

The Yes California movement advocated full-on secession from the rest of the country, and it gained steam after Donald Trump won the presidential election in 2016. However, as the Sacramento Bee noted, that attempt failed to gather the signatures needed and further floundered after it was accused of having ties to Russia.

But as the Los Angeles Times reported this week:

“On Tuesday afternoon, Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra’s office released an official title and summary for the initiative, now called the ‘California Autonomy From Federal Government’ initiative.”

The new measure that seeks to set up an advisory commission to inform California’s governor on ways to increase independence from the federal government. It would reportedly cost $1.25 million per year to fund “an advisory commission to assist the governor on California’s independence plus ‘unknown, potentially major, fiscal effects if California voters approved changes to the state’s relationship with the United States at a future election after the approval of this measure,’” the Los Angeles Times reported.

With Becerra’s approval, its backers can now seek the nearly 600,000 signatures required to place the measure on the 2018 ballot.

As the outlet explained:

“The initiative wouldn’t necessarily result in California exiting the country, but could allow the state to be a ‘fully functioning sovereign and autonomous nation’ within the U.S.’”

According to the Attorney General’s official document on the measure, it still appears to advocate secession as the ultimate goal — even if it doesn’t use the term outright.“Repeals provision in California Constitution stating California is an inseparable part of the United States,” the text explains, noting that the governor and California congress members would be expected “to negotiate continually greater autonomy from federal government, up to and including agreement establishing California as a fully independent country, provided voters agree to revise the California Constitution.”

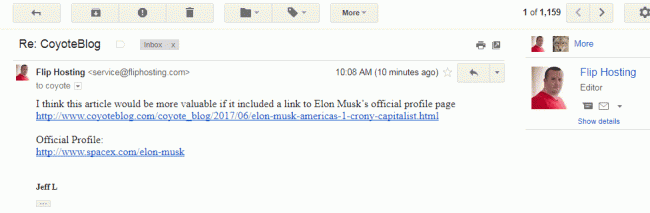

Weirdly Desperate Publicity Plea from Elon Musk?

I found this email to be simply bizarre. If this is anything more than odd PR, I am not sure I understand it (the links are what they claim to be, rather than some sort of Phishing). It clearly is a bot because no human would have actually read the article and thought that Elon Musk would really like me to better tie my article on his rent-seeking to his other PR. Anyone know what is going on here? I can't believe that Internet billionaire Elon Musk is paying Flip Hosting for some sort of crappy SEO work based on Google link-based page-rank schemes that are several years out of date.

I am Going To Make A Fortune in the New Legalized Marijuana Market.... Uh, Maybe Not

Here are Coyote's first three rules of business strategy:

- If people are entering the business for personal, passionate, non-monetary reasons then the business is likely going to suck. When I say "suck", I mean there may be revenues and customers and even some profits, but that the returns on investment are going to be bad**. Typically, the supply of products and services and the competitive intensity in an industry will equilibrate over time -- if profits are bad, some competitors exit and the supply glut eases. But if people really love the industry and do not want to work anywhere else and get emotional benefits from working there, there always tends to be an oversupply problem. For decades, maybe its whole history, the airline industry was like this. The restaurant industry is this way as well. The brew pub industry is really, really like this -- go to any city and check the list of small businesses for sale, and an absurd number will be brew pubs.

- If the business is frequently featured in the media as the up and coming place to be and the hot place to work, stay away. Having the media advertising for new entrants is only going to increase the competitive intensity and exacerbate the oversupply problem that every fast-growing industry inevitably faces as it matures.

- Beware the lottery effect -- One or two people who made fortunes in the business mask the thousands who lost money (Freakonics had an article on the drug trade positing that it works just this way -- while many of us assume the illegal drug trade makes everyone in it rich, in fact only a few really do so and the vast majority are and always will be grinders making little money for high risk). Even those people who made tons of money in hot businesses sometimes just had good timing to get out at the right time before the reckoning came. Mark Cuban is famous as an internet billionaire, but in fact Broadcast.com, which he sold for over $5 billion to Yahoo, only had revenues in its last independent quarter of about $14 million and was losing money (that's barely four times larger than my small company).

When I was at Harvard Business School, the first two cases in the first week of strategy class were a really cool high-tech semiconductor fab and a company that makes brass water meters that are sold to utilities. After we had read the cases but before we discussed them, the professor asked us which company we would like to work for. Everyone wanted the tech firm. But as we worked through the cases, it became clear that the semiconductor firm had an almost impossible profitability problem, while Rockwell water meters minted money. I never forgot that lesson - seemingly boring industries could be quite attractive, and this lesson was later hammered home for me as I later was VP of corporate strategy for Emerson Electric, a company that was built around making money from boring but profitable industrial products businesses.

Of course there are exceptions, but almost every one of these have built some sort of competitive advantage that allowed them to rise above the rivalry. Google and Facebook are sexy and make money, but they have built scale and network effect advantages that make them hard now to challenge. Apple makes money now because it has created switching costs (try switching from an iPhone to an Android and ever being able to text again with iPhone users) and a powerful brand. The NFL owners have enormously sexy businesses but have created a brand and other competitive restrictions that protect their positions (not to mention have perfected the art of sucking money out of taxpayers for stadiums). But even looking at these examples, the world is littered with folks who tried to be in the same business and failed. Remember Nokia, Blackberry, Motorola, Lycos, Yahoo, AOL, Netscape, USFL, XFL, Myspace, etc. I don't really know how strategy is being taught today, but I was schooled at HBS in Michael Porter's five forces. I still find this framework useful, and probably about as much as any layman needs to know about business strategy.

But what about marijuana? There are a lot of people very passionate about marijuana. It is easy to grow (I remember an ex-girlfriend way back in the eighties whose mom grew it in the attic) and easy to sell (there is plenty of retail space nowadays going begging, or there is always the internet). Every time there is some expansion opportunity in the business (e.g. a new state legalizing) the fact is advertised all over the media. Overall, most folks are going to fail and most investment is not going to have very good returns for all the reasons listed above. For most entrants, marijuana is gong to suck as a business for years to come. And, some states seem to be developing onerous licensing regimes, and this may allow a few folks with the coveted licenses to make pretty good money. Some day there could well be someone who consolidates the business and builds a powerful consumer brand and drives down costs and increases scale that makes money in marijuana. But that is years away and typically the person who leads this is not among the initial entrants. Remember, the vast vast majority of folks who traveled to California in the 1849 gold rush never made a cent.

You can already see this in California (my emphasis added).

California's marijuana growers are producing far more pot than is consumed in-state — and will be forced to reduce crops under new regulations that ban exports, the Los Angeles Times reported.

"We are producing too much," Allen told the Sacramento Press Club during a panel discussion, the Times reported; he added that state-licensed growers "are going to have to scale back. We are on a painful downsizing curve."

Estimates vary for just how much surplus California produces — anywhere from five times to 12 times what is consumed in-state, the Times reported.

** You can tell I have classical training in business strategy because my goal is return on investment. One can argue, perhaps snarkily but also somewhat accurately, that there is a new school of thought that does not care about profitability, revenues, or return on investment but on getting larger and larger valuations from private investors based on either user counts or just general buzz. I am entirely unschooled in this modern form of strategy. However, the general strategy of getting someone to overpay for something from you is as old as time. I mentioned Mark Cuban but there are many other examples. Donald Trump seems to have made a lot of money from a related strategy of fleecing his debt holders.

Keeping Cocktails Cold Without Dilution

For many of you, this will be a blinding glimpse of the obvious, but I see so many dumb approaches to cooling cocktails being pushed that I had to try to clear a few things up.

First, a bit of physics. Ice cubes cool your drink in two ways. First and perhaps most obviously, the ice is colder than your drink. Put any object that is 32 degrees in a liquid that is 72 degrees and the warmer liquid will transfer heat to the cooler object. The object you dropped in will warm and the liquid will cool and their temperatures will tend to equilibrate. The exact amount that the liquid will cool depends on their relative masses, the heat carrying capacity of each material, and the difference in their temperatures.

However, for all but the most unusual substances, this cooling effect will be minor in comparison with the second effect, the phase change of the ice. Phase changes in water consume and liberate a lot of heat. I probably could look up the exact amounts, but the heat absorbed by water going from 32 degree ice to 33 degree water is way more than the heat absorbed going from that now 33 degree water to room temperature.

Your drink needs to be constantly chilled, even if it starts cold, because most glasses are not very good insulators. Pick up the glass -- is the glass cold from the drink? If so, this means the glass is a bad insulator. If it were a good insulator, the glass would be room temperature on the outside even if the drink were cold. The glass will absorb some heat from the air, but air is not really a great conductor of heat unless it is moving. But when you hold the glass in your hand, you are making a really good contact between your drink and an organic body that is essentially circulating near-100 degree fluid around it. Your body is pumping heat into your cocktail.

Given this, let's analyze two common approaches to supposedly cooling cocktails without excessive dilution:

- Cold rocks. You put these things in the freezer and put them in your drink to keep it cold. Well, this certainly will not dilute the drink, but it also will not keep it very cold for long. Remember, the equilibration of temperatures between the drink and the object in it is not the main source of heat absorption, it is the phase change and the rocks are not going to change phase in your drink. Perhaps if you cooled the rocks in liquid nitrogen? I don't know.

- Large round ice balls. There is nothing that is more attractive in my cocktail than a perfect round ice ball. A restaurant here in town called the Gladly has a way of making these beautiful round flaw-free ice balls that look like they are Steuben glass. The theory is that with a smaller surface to volume ratio, the ice ball will melt slower. Which is probably true, but all this means is that the heat transfer is slower and the cooling is less. But again, the physics should be roughly the same -- it is going to cool mostly in proportion to how much it melts. If it melts less, it cools less. I have a sneaking suspicion that bars have bought into this ice ball thing to mask tiny cocktails -- I have been to several bars which have come up with ice balls or cylinders that are maybe 1 mm smaller in diameter than the glass so that a large glass holds about an ounce of cocktail.

I will not claim to be an expert but I like my bourbon drinks cold and have adopted this strategy -- perhaps you have others.

- Keep the bottles chilled. I keep Vodka in the freezer and bourbon and a few key mixers in the refrigerator. It is much easier to keep something cool than to cool it the first time, and this is a good dilution-free approach to the initial cooling. I don't know if this sort of storage is problematic for the liquor -- I have never found any issues.

- Keep your drinking glass in the freezer. Again, it will warm in your hand but an initially warm glass is going to pump heat into whatever you pour into it.

- Use a special glass. I have gone through two generations on this. My first generation was to use a double wall glass with an air gap. This works well and you can find many choices on Amazon. Then my wife found some small glasses at Tuesday Morning that were double wall but have water in the gap. You put them in the freezer and not only does the glass get cold but the water in the middle freezes. Now I can get some phase change cooling in my cocktail without dilution. You have to get used to holding a really cold glass but in Phoenix we have no complaints about such things.

Things I don't know but might work: I can imagine you could design encapsulated ice cubes, such as water in a glass sphere. Don't know if anyone makes these. There are similar products with gel in them that freezes, and double wall glasses with gel. I do not know if the phase change in the gel is better or worse for heat absorption than phase change of water. I have never found those cold packs made of gel as satisfactory as an ice pack, but that may be just a function of size. Anyone know?

Update: I believe this is what I have, though since we bought them at Tuesday Morning their provenance is hard to trace. They are small, but if you are sipping straight bourbon or scotch this is way more than enough.

Postscript: I was drinking old Fashions for a while but switched to a straight mix of Bourbon and Cointreau. Apparently there is no name for this cocktail that I can find, though its a bit like a Bourbon Sidecar without the lemon juice. For all your cocktails, I would seriously consider getting a jar of these, they are amazing. The Luxardo cherries are nothing like the crappy bright red maraschino cherries you see sold in grocery stores.

Well, It's Good Princeton Is Against Gender Stereotyping, Because Otherwise This Would Be Pretty Obvious Gender Stereotyping

From the College Fix (my empahasis added):

Are young men at Princeton University violent, aggressive, hyper-masculine, stalkers, or rapists?

A new position at the Ivy League institution indicates campus officials apparently think enough of its male students grapple with such problems that it warrants hiring a certified clinician dedicated to combating them.

The university is in the process of hiring an “Interpersonal Violence Clinician and Men’s Engagement Manager†who will work with a campus office called SHARE that’s dedicated to “survivors†of sexual harassment, assault, dating violence and stalking.

According to SHARE, one in four female undergrads experienced such misconduct during the 2015-16 school year.

The men’s manager will also launch initiatives to challenge “gender stereotypes,†and expand the school’s Men’s Allied Voices for a Respectful and Inclusive Community, a self-described “violence prevention program†at Princeton that often bemoans “toxic masculinity†on its Facebook page.

According to the job description, the men’s manager will develop educational programs targeting the apparent “high-risk campus-based populations for primary prevention of interpersonal violence, including sexual harassment, sexual assault, domestic/dating violence, and stalking.â€

The job posting implicitly refers to men as perpetrators and women as victims.

Fortunately, stereotyping does not count if done about men, whites, or heterosexuals so this is all OK.

By the way, apparently since the one in five statistic was not absurd enough, SJW's have upped the ante with a new one in four stat. I am all for aggressive responses to actual violence, and would be more harsh in its punishment than most universities (I would throw the perpetrator into the legal system, rather than merely some administrative punishment and expulsion regime.) The problem is that I do not know the actual rate of violence. The one in five, and now one in four stat is almost certainly bullsh*t. If this were really true, college campuses would be more dangerous than Syria and people would not be competing so hard and paying so much to send their daughters there.

The problem with these stats is that they hoover up all sorts of complaints by women that range from true violence down to things like boorish comments by males and post-sex regret. By rhetorical slight of hand, all these complaints are morphed into violence and every complaint, no matter how trivial, is essentially counted as a rape. Perhaps sexual assault on campus is indeed more common than in the broader community, but if so I would like to see real statistics. When advocates purposely inflate and obfuscate their core statistic, it makes me suspicious that the actual number is not really that bad and therefore a fake one needs to be provided instead for the activist to get my attention. But for me, this has the opposite effect, turning me off on an issue I perhaps should be energized about because I can't see past the fakery.

Public vs. Private Management: Marketing Videos and Hot Dogs

One of the more popular features we have been experimenting with is adding aerial video of campgrounds we operate shot from small drones. Customers love these and find them a great way to experience the campground before the commit to a visit. Here is an example:

We have done this for all the campgrounds where we have a long-term lease and substantial leeway in operating the park. However, we have not yet done any videos for the scores of Forest Service. Perhaps this is why -- here is what I have to do to film a campground the FS has already contracted us to operate and market:

We ask for at least 2 weeks advance notice in order to prepare a permit and have the documentation reviewed by our aviation staff. The proposal would need to include how your drone operations would address public safety and impacts to users in the campgrounds (I believe that you have to have people’s permission to film them so how to avoid that). Also as you stated all activities would stay above your sites – no flights above Wilderness or the creek or adjacent canyons. Due to listed species in the canyon, drone activity would need to occur after September 1 which is after the spotted owl breeding season. The drone would need to be operated by a FAA licensed commercial drone operator and we would need documentation of a FAA Part 107 Remote pilots license or COA from the FAA. In addition, we would need to have the operator coordinate with our aviation manager and provide the below information, with direction to be included in a permit so they can get the information out to our aviation assets in the area:

All approved areas on the forest are to be used at your own risk while adhering to all FAA rules and regulations for UAS operations. Notification to the Forest Interagency Aviation Officer at least 24 hours prior to operations is required to help de-conflict airspace with fire aircraft and other forest aviation assets. Include in your notification:

- Date, time and location of flight

- Names and contact information of pilot(s)

- Make and model of UAS

Fees are based on crew size, 1-10 people for video is $150/day.

Several years ago, I was at a meeting in Washington with senior leaders in the Department of Agriculture, including from the Forest Service, and from a number of other recreation agencies. (You never thought of the Department of Agriculture as a recreation agency did you? They may have more total recreation sites (not visitation, but absolute number of locations) than Department of Interior. Anyway, these senior leaders were talking about being more visitor-focused. They were talking about sophisticated programs to provide all sorts of innovative visitor services, and after a while I just started laughing. They asked me why, and I pulled up on my tablet a letter I had just received from a Forest Service District Ranger (the lowest level line officer) who denied my request to make and sell hot dogs at a store next to a busy Florida swimming hole we run.

While we appreciate your attempt to provide additional services to recreationists, this service is not consistent with current services offered in other recreation areas. As a Forest, we would like to provide recreationists with the bare necessities to ensure that their visit is enjoyable. The sale of hot dogs and nachos is out of that scope.

Public Choice and "Privilege"

A key thrust of Nancy MacLean's book on the great Koch / Buchanan / libertarian conspiracy to destroy democracy is that public choice theory is all about protecting and cementing elite privilege under the law. This is actually exactly opposite of how I have always viewed public choice theory -- public choice theory tends to show how well-intentioned "public service" programs tend to get co-opted by a few powerful people for their own benefit. See "ethanol mandates" or "steel tariffs" or "beautician licensing" or any number of other programs. But I am not conversant enough to really make this case well. Fortunately, Steven Horwitz (pdf) has done it in his powerful critique of MacLean's book.

The intellectual error that is most frustrating, however, is her understanding of the relationship between public choice theory and questions of power and privilege. As Munger (2018) points out in his review, MacLean is an unreconstructed majoritarian. She genuinely believes, at least in this book, that the majority should always be able to enact its preferences and that constitutional constraints on majority rule are ways of protecting the power and privilege of wealthy white males. That’s the source of Democracy in Chains as her title and her argument that public choice theory is a tool of the powerful elite. As Munger also observes, normally such a view would be seen as a strawman as no serious political scientist believes it, not to mention that no democracy in the world lacks constitutional constraints on majorities. In addition, one must presume that a progressive like MacLean thinks Loving v. Virginia, Roe v. Wade, and Obergefell v. Hodges, not to mention Brown, were all decided correctly, even though all of them put local democracies in chains, and in some cases, thwarted the expressed preferences of a majority of Americans.

For public choice theory, constitutions protect the citizens from two forms of tyranny: tyrannies of the majority when they wish to violate rights and tyrannies of coalitions of minorities who wish to use the state to redirect resources to themselves by taking advantage of the logic of concentrated benefits and diffuse costs. Buchanan’s political vision is, in Peter Boettke’s words, a world without discrimination and domination. Constitutional constraints, for Buchanan, are a central way of ensuring that democracy actually protects rights by preventing the powerful from exploiting the powerless and that political decisions involve the consent of all. Constitutional constraints make democracy work for all citizens – they do not put it in chains.

When MacLean argues that public choice is a tool to protect privilege, she gets it exactly backward. Public choice shows us how those with the power to influence the political process can use that power to create and protect privilege for themselves at the expense of the rest of the citizenry. Public choice’s analysis of rent-seeking and politics as exchange enables us to strip off the mask of bogus “public interest” explanations and see a great deal of political activity as socially destructive exploitation of the least well-off. To borrow a bit from the left’s rhetoric: public choice is better seen as a tool of resistance to oligarchy than a defense thereof. It helps us understand why corporate welfare remains so common even as so many see it as a problem. Public choice also helps to understand the growth of the military-industrial complex and challenges public interest explanations of that growth. One can tell similar stories about immigration policy and a number of other issues of that concern modern progressives. Public choice theory sees the battles over Uber and Lyft as the powerful government-licensed taxi companies fighting to protect their monopoly privileges and profits against upstart entrepreneurs better meeting the wants of the public. This provides an excellent illustration of how public choice theory can explain political outcomes, and why the theory is useful in understanding how the powerful can victimize the less powerful. Public choice theory, properly understood, is a tool of critical thinking that enables us to deconstruct political rhetoric to see the underlying forces at work that are allowing those with wealth and access to power to use politics to acquire and protect their privileges and profits

As Arnold Kling might say, and Horowitz himself posits in different words, libertarians spend so much time obsessing over the freedom-coercion political axis that they miss out on ways to engage those on the Oppressor-Oppressed axis. Public choice theory has a lot to offer Progressives, as it explains a lot about how well-meaning legislation with progressive intent is often co-opted by powerful groups to enrich themselves. Sure a lot of public choice theory is used by libertarians to say, essentially, burn the whole government to the ground; but there is a lot from my experience in public choice literature that should speak to good government progressives, academic work using public choice to think about better designing programs to more closely achieve their objectives.

Controlling Window Opacity With A Switch

I have seen companies advertising this sort of switchable privacy glass, but I had never seen it in the wild. Had this glass in my hotel this weekend. Really cool. If they can perfect glass that goes full dark or opaque with a switch, I have a ton of windows I would like to replace (sorry for the small image, playing with Google's new Motion Stills app to make gif's, but it does not seem to have a save to disk function so I had to text it to myself and this was all the resolution I got).

Politicians Will Burn Down Anything That Is Good Just To Get Their Name In The News

a group of 12 Democratic Congressman have signed a letter urging the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission to conduct a more in-depth review of e-commerce giant Amazon.com Inc.'s plan to buy grocer Whole Foods Market Inc., according to Reuters.

Rumblings that Amazon is engaging in monopolistic business practices resurfaced last week when the top Democrat on the House antitrust subcommittee, David Civilline, voiced concerns about Amazon's $13.7 billion plan to buy Whole Foods Market and urged the House Judiciary Committee to hold a hearing to examine the deal's potential impact on consumers.

Making matters worse for the retailer, Reuters reported earlier this week that the FTC is investigating the company for allegedly misleading customers about its pricing discounts, citing a source close to the probe.

The letter is at least third troubling sign that lawmakers are turning against Amazon, even as President Donald Trump has promised to roll back regulations, presumably making it easier for megamergers like the AMZN-WFM tieup to proceed.

It is difficult even to communicate how much Amazon has improved my life. I despise going to stores, and Amazon allows me the pick of the world's consumer products delivered to my home for free in 2 days. I love it. So of course, politicians now want to burn it down.

I say this because the anti-trust concerns over the Whole Foods merger have absolutely got to be a misdirection. Whole Foods has a 1.7% share in groceries and Amazon a 0.8%. Combined they would be the... 7th largest grocery retailer and barely 1/7 the size of market leader Wal-Mart, hardly an anti-trust issue. So I can only guess that this anti-trust "concern" is merely a pretext for getting a little bit of press for attacking something that has been successful.

The actual letter is sort of hilarious, in it they say in part:

in the letter, the group of Democratic lawmakers – which includes rumored presidential hopeful Cory Booker, the junior senator from New Jersey – worried that the merger could negatively impact low-income communities. By putting other grocers out of business, the Amazon-backed WFM could worsen the problem of “food deserts,” areas where residents may have limited access to fresh groceries. "While we do not oppose the merger at this time, we are concerned about what this merger could mean for African-American communities across the country already suffering from a lack of affordable healthy food choices from grocers," the letter said on Thursday.

Umm, the Amazon model is being freed from individual geographic locations so that everyone can be served regardless of where they live. This strikes me as the opposite of "making food deserts worse." It is possible that Amazon might not deliver everywhere at first, and is more likely to deliver to 90210 than to Compton in the first round of rollouts. But either they do deliver to a poor neighborhood, and improve choices, or they don't, and thus have a null effect. And it is really sort of hilarious worrying that new ownership of Whole Foods, of all groceries, is going to somehow devastate poor neighborhoods.

By the way, if I were an Amazon shareholder, I would be tempted to challenge Bezos on his ownership of the Washington Post. In a free society, he is welcome to own such a business and have that paper take whatever editorial stands he wishes. However, we do not live in a fully free society. As shown in this story, politicians like to draw attention to themselves by using legislation and regulation to gut successful companies, particularly ones that tick them off personally. In this case:

So far, it’s mostly Democrats who are urging the FTC to take “a closer look” at the deal. However, some suspect that Amazon founder Jeff Bezo’s ownership of the Washington Post – a media outlet that has published dozens of embarrassing stories insinuating that Trump and his compatriots colluded with Russia to help defeat Democrat Hillary Clinton – could hurt the company’s chances of successfully completing the merger, as its owner has earned the enmity of president Trump. Similar concerns have dogged CNN-owner Time Warner’s pending merger with telecoms giant AT&T.

Movie Special Effects Before CGI

I am a sucker for both 70's disaster movies and well-crafted pre-CGI special effects. So I enjoyed this article on the special effects techniques in The Towering Inferno. The 70-foot high model is amazing.

[Fill in Name of Government Program] Would Have Worked Had the Right Person Been Running It

I have disputed the meme in the post's title on many occasions. For example:

- No person running any government agency has access to the same information that millions of individuals might have in making decisions for themselves

- No person running any government agency can create an optimal solution, because millions of citizens all have different values and make different tradeoffs, so an optimum for one is not going to be an optimum for many others

- No person running any government agency has the right incentives to make good decisions. They will always optimize for increasing the size and scope of their organization and signaling virtue over actually being virtuous.

But researchers have found yet another reason: power causes brain damage

A spate of recent articles corroborate what I already suspected, that holding elected office is the neurological equivalent of getting kicked in the head by a donkey.

"Subjects under the influence of power," Dacher Keltner, a professor atUniversity of California, Berkeleyfound, "acted as if they had suffered a traumatic brain injury—becoming more impulsive, less risk-aware, and, crucially, less adept at seeing things from other people's point of view."

In other words, power turns people into sociopaths.

This isn't a huge surprise to the vast majority of us who rant about power on election day and every day afterward. Republicans and Democrats want power and scramble for it, like a football. Classical liberals see power more like Frodo's ring—a corrupting influence better chucked into a volcano. In light of recent studies we ought to consider it a bit more like a concussion.

Keltner, brought into the public spotlight through a recent piece in The Atlantic, likens the accruing of power to actual brain trauma: "My own research has found that people with power tend to behave like patients who have damaged their brain's orbitofrontal lobes (the region of the frontal lobes right behind the eye sockets), a condition that seems to cause overly impulsive and insensitive behavior. Thus the experience of power might be thought of as having someone open up your skull and take out that part of your brain so critical to empathy and socially-appropriate behavior."

A Net Neutrality Parable

I have been frustrated trying to explain to folks why net neutrality is anything but neutral, in fact tilting the playing to the advantage of large content providers. I thought I would take a lesson from Don Boudreaux, who has spent a lot of time thinking about economics education. He often works by analogy -- sometimes these analogies work for me and sometimes they don't, but they seem a good way to reach people perhaps when traditional arguments have not worked.

Let's consider two cities we will call Gotham and Metropolis. One day a private road builder proposes the first major highway between the two cities. The citizens cheer, but the government places one caveat on them -- the builders must be neutral to all traffic. Every entity (individuals, corporations, public agencies) should each pay the same fixed amount each year for use of the road and everyone should get equal access to the road, no matter how much they use it.

Things start out pretty much as expected. The company sets the access charge at $10 a year, and lots of entities pay to put their one or two vehicles on the road from time to time. The road is a great time saver and the capacity of two lanes in each direction is more than enough for easy, fast travel.

This new road and the faster transportation it allows spawns a number of entrepreneurs who find new uses for the road. In particular, two companies create new logistics services that cause at first dozens, then hundreds, and then thousands of their trucks to hit the road between the two cities. Soon, more than half the vehicles on the road are from these two companies, and another 25% of the vehicles on the road are from perhaps a dozen smaller imitators. But each of these companies, despite using orders of magnitude more of the road's capacity than any other individual, still pay the same flat $10 for access to all their vehicles. These trucking companies continue to add new services -- such as high demand logistics (HD for short) -- that put more and more trucks on the highway. Traffic explodes. It turns out that these trucking companies have ways to compress their loads into fewer trucks with little loss to their quality of service, but why bother? They are not paying for the capacity they are using, so why conserve?

But the resulting congestion from these few companies' trucks is slowing everyone else down. Congestion reigns. Instead of blaming the trucking companies, everyone demands the road company add more capacity, which they do. They spend huge amounts of money to accommodate the traffic from these few companies, but due to neutrality rules the costs get paid by everyone, and the annual fee goes up to $15, $20, then $25. Finally, a few people begin to observe that their access fees have doubled and tripled all to support vehicles from just a few entities. Proposals come forward: Can't these trucks be limited to certain lanes to keep them out of the way of other traffic? Can't they be limited at certain times of day? Can't the road company charge them per vehicle, rather than a flat fee, so they pay their fair share of the expansion costs? Can't the road company give them incentives to compress their loads into fewer trucks? Can't the trucking companies make a contribution to the capital fund to expand the road?

But nothing happens, because of road neutrality. The trucking companies repeatedly shout "road neutrality" and conduct a successful campaign to convince everyone else that road neutrality is really in their interest. They try to scare individuals by saying that an end to road neutrality will cause certain drivers to be excluded just because the road company does not like them, when in fact no such proposal or issue has ever existed. Just to be sure, the trucking companies pack the regulatory boards with their cronies.

I hope the analogy is, while not perfect, at least clear. Google (via Youtube), Netflix, and Facebook account for over half the bandwidth used on the Internet. They claim they are worried about ISP's filtering traffic based on political views, but no one has ever provided the smallest shred of evidence that this occurs (and it is incredibly hypocritical since Facebook and Google do exactly this within their platforms). What they are really worried about is that someone might un-bundle your local Internet service, specifically splitting the high bandwidth using sites from the low. An ISP might very rationally offer a much lower monthly rate to someone who accepted a plan that did not allow streaming video or which compressed streaming video to conserve bandwidth (oddly, while the Left supports net neutrality, they favor the opposite in cable TV, trying to force unbundling of sites that are cheap for cable companies to provide from those that are expensive (e.g. ESPN). This is likely Google and Netflix's nightmare.

One way to think about this is a classic vertical supply chain fight. Suppliers and their channel fight all the time to see who will reap the lion's share of the profits available from selling to the end consumer. There is a certain amount to be made from selling an incremental streaming movie -- Netflix and your ISP both want a piece, Netflix for the content and the ISP for building the pipe. In a free market, they would fight it out, and the accommodations between them would likely ebb and flow over time. What net neutrality does is attempt to impose a resolution of this such that Google and Netflix get 100% of the revenue and the ISP is saddled with 100% of the cost to build the pipe. Hardly "neutral".

Postscript: Google is also worried than an ISP might hook up with, say, Netflix and offer Netflix for free to their low-bandwidth products sort of as a preferred provider. Sort of exactly like what Google does with every one of its own services, given them preferred position in their search engine. Hypocrites all.

For the Record, I Fear Pure Majoritarian Democracy as Well

One of the themes of Nancy Maclean's new book on James Buchanan as the evil genius behind a conspiracy to unravel democracy in this county. In critiquing her critique, I meant to also make it clear that whatever Buchanan may have believed on the subject, I am certainly skeptical of pure majoritarian democracy. For me, protection of individual rights is the role of government, and populist majoritarianism can easily conflict with this goal (this is not a new finding, we pretty much figured this out after Julius Caesar, if not before. Here was a piece I wrote years ago I will repeat here:

Every Memorial Day, I am assaulted with various quotes from people thanking the military for fighting and dying for our right to vote. I would bet that a depressing number of people in this country, when asked what their most important freedom was, or what made America great, would answer "the right to vote."

Now, don't get me wrong, the right to vote in a representative democracy is great and has proven a moderately effective (but not perfect) check on creeping statism. A democracy, however, in and of itself can still be tyrannical. After all, Hitler was voted into power in Germany, and without checks, majorities in a democracy would be free to vote away anything it wanted from the minority - their property, their liberty, even their life. Even in the US, majorities vote to curtail the rights of minorities all the time, even when those minorities are not impinging on anyone else. In the US today, 51% of the population have voted to take money and property of the other 49%.

In my mind, there are at least three founding principles of the United States that are far more important than the right to vote:

- The Rule of Law. For about 99% of human history, political power has been exercised at the unchecked capricious whim of a few individuals. The great innovation of western countries like the US, and before it England and the Netherlands, has been to subjugate the power of individuals to the rule of law. Criminal justice, adjudication of disputes, contracts, etc. all operate based on a set of laws known to all in advance.

Today the rule of law actually faces a number of threats in this country. One of the most important aspects of the rule of law is that legality (and illegality) can be objectively determined in a repeatable manner from written and well-understood rules. Unfortunately, the massive regulatory and tax code structure in this country have created a set of rules that are subject to change and interpretation constantly at the whim of the regulatory body. Every day, hundreds of people and companies find themselves facing penalties due to an arbitrary interpretation of obscure regulations (examples I have seen personally here).

- Sanctity and Protection of Individual Rights. Laws, though, can be changed. In a democracy, with a strong rule of law, we could still legally pass a law that said, say, that no one is allowed to criticize or hurt the feelings of a white person. What prevents such laws from getting passed (except at major universities) is a protection of freedom of speech, or, more broadly, a recognition that individuals have certain rights that no law or vote may take away. These rights are typically outlined in a Constitution, but are not worth the paper they are written on unless a society has the desire and will, not to mention the political processes in place, to protect these rights and make the Constitution real.

Today, even in the US, we do a pretty mixed job of protecting individual rights, strongly protecting some (like free speech) while letting others, such as property rights or freedom of association, slide.

- Government is our servant. The central, really very new concept on which this country was founded is that an individual's rights do not flow from government, but are inherent to man. That government in fact only makes sense to the extent that it is our servant in the defense of our rights, rather than as the vessel from which these rights grudgingly flow.

Statists of all stripes have tried to challenge this assumption over the last 100 years. While their exact details have varied, every statist has tried to create some larger entity to which the individual should be subjugated: the Proletariat, the common good, God, the master race. They all hold in common that the government's job is to sacrifice one group to another. A common approach among modern statists is to create a myriad of new non-rights to dilute and replace our fundamental rights as individuals. These new non-rights, such as the "right" to health care, a job, education, or even recreation, for god sakes, are meaningless in a free society, as they can't exist unless one person is harnessed involuntarily to provide them to another person. These non-rights are the exact opposite of freedom, and in fact require enslavement and sacrifice of one group to another.

I will add that pretty much everyone, including likely Ms. Maclean, opposes majoritarian rule on many issues. People's fear of dis-empowering the majority tends to be situational on individual issues.

Regulators Are Almost By Definition Anti-Consumer

Free markets are governed and regulated by consumers. If suppliers offer something, and consumers like it and like how that particular supplier provides it more than other choices they have, the supplier will likely prosper. If suppliers attempt to offer consumers something they don't want or need, or already have enough of from acceptable sources, the supplier will likely wither and disappear. That is how free markets work. Scratch a Bernie Sanders supporter and you will find someone who does not understand this basic fact of consumer sovereignty.

Regulators generally are operating from a theory that says there is some sort of failure in the market, that consumers are not able to make the right choices or are not offered the choices they really want and only the use of force by regulators can fix this failure. In practice, regulators have no way of mandating a product or service that producers cannot economically or technically provide (see: exit from Obamacare exchanges) and so all they actually do is limit choice by pruning products or services or individual features the regulators don't think consumers should be offered. They substitute the judgement of a handful of people for the judgement of thousands, or millions, and ignore that there is not some single Platonic ideal of a product out there, but thousands or millions of ideals based on the varied preferences of millions of people.

A reader sends me a fabulous example of this from the Socialist Republic of Cambridge, Mass.

Month after month, in public meeting after public meeting, a trendy pizza mini-chain based in Washington, D.C., hacked its way through a thicket of bureaucratic crimson tape in the hopes of opening up shop in a vacant Harvard Square storefront. But when the chain, called &pizza, arrived at the Cambridge Board of Zoning Appeal in April, the thicket turned into a jungle.

Harvard Square already has plenty of pizza, board chairman Constantine Alexander declared, and though a majority of the board signed off on &pizza’s plans, approval required a four-vote supermajority. Citing the existence of five supposedly similar pizza joints in the area, as well as concerns about traffic congestion, a potential “change in established neighborhood character,†and even the color of the restaurant’s proposed signage, Alexander and cochair Brendan Sullivan dissented.

“A pizza is a pizza is a pizza,†Alexander said at one point during the April hearing, sounding suspiciously like someone who doesn’t eat much pizza or give much thought to the eating habits of the 22,000 or so college students who live in the city.

A city ordinance dictates that any new fast-food place should be approved only if it “fulfills a need for such a service in the neighborhood or in the city.†But the notion that an unelected city board should be conducting market research using some sort of inscrutable eye test to decide precisely what kind of cuisine is appropriate for Harvard Square stretches that to the point of absurdity.

So I Was Wrong Again -- American Politics and No Way Out

About 30 years ago there was a Kevin Costner movie called "No Way Out". If you never saw it and ever intend to, there is a major spoiler coming. Anyway, Costner is a military officer having a fling with a woman played by Sean Young, who is also having a fling with Costner's superior officer. Sean Young turns up dead (probably a fantasy for the director since every director who worked with her wanted to kill her). There is some sense that Costner's superior officer may be guilty, and Costner is named by the officer to lead the investigation, but with a twist -- the officer is trying to get the girl's death blamed on a mysterious Russian spy, who may or may not even be real, to divert attention from his adultery and possibly from the fact that he was probably the killer. Things evolve, and it appears that Costner is going to be framed not only for the girl's death but also as the probably mythical spy. The movie is about Costner desperately trying to escape this frame, and in the end is successful. But in the final scene, Costner is seen speaking in Russian to his controller. He is the spy! The original accusation was totally without evidence, almost random, meant to divert attention from his superior's likely crimes, but by accident they turned out to be correct.

I feel like that with the Russian election hacking story. For months I have said the Russian election hacking story was a nothing. It made little sense and there was pretty much zero evidence. It was dreamed up within 24 hours of the election by a Clinton campaign trying to divert attention and blame for their stunning loss. I have called it many times the Obama birth certificate story of this election.

But it turns out that pursuing any Trump connection whatsoever with Russia has turned up some pretty grubby stories. In particular, seeing a Presidential campaign -- and the President's son -- fawning over unfriendly foreign governments to get their hands on oppo research is just plain ugly. That the Clinton campaign may have done shady things to get oppo research of their own is irrelevant to the ethics here (and perhaps one good justification for electing Republicans, since the media seems to be more aggressive at holding Republicans to account for such things).

Sorry. I fell victim to one of the classic blunders - the most famous of which is "never get involved in a land war in Asia" - but only slightly less well-known is this: "Never underestimate the stupidity and ethical flexibility of politicians."

Postscript: In general, my enforced absence from both twitter and highly partisan blogs is going quite well. I will write more about it soon, but I have to mention this: I had a small break in my isolation yesterday when I was scanning around the radio on a business trip. I landed on Rush Limbaugh, and would have moved on immediately but the first words I heard out of his mouth were "golden showers". OK, I was intrigued. He then used that term about 3 more times in the next 60 seconds (apparently he was going with the "everybody does it" defense of Trump by accusing the Clintons of getting oppo research from the Ukraine, or whatever). Anyway, any issue that has a Conservative talk show host discussing golden showers from Russian hookers can't be all bad.

The Culture That is Ausralia

Australian man successfully checks single can of beer on his flight.

This Aussie checked his can of beer for his flight! ? #dedication https://t.co/TzPA6lpJIs pic.twitter.com/8WDlT1e2Wv

— Bottoms Up Beer (@BottomsUpBeer) July 10, 2017

$150 Million in Lost Tax Money Later, Another Sorry Tale Of Government "Investment" Hopefully Comes to An End

Years ago I wrote about the Sheraton hotel the city built:

For some reason, it appears that building hotels next to city convention centers is a honey pot for politicians. I am not sure why, but my guess is that they spend hundreds of millions or billions on a convention center based on some visitation promises. When those promises don't pan out, politicians blame it on the lack of a hotel, and then use public money for a hotel. When that does not pan out, I am not sure what is next. Probably a sports stadium. Then light rail. Then, ? It just keeps going and going....

When Phoenix leaders opened the Sheraton in 2008, they proclaimed it would be a cornerstone of downtown's comeback. They had one goal in mind: lure big conventions and tourism dollars. Officials argued the city needed the extra hotel beds to support its massive taxpayer-funded convention center a block away.

Finally, we may be at an end, though politicians are still hoping for some sort of solution that better hides what a sorry expenditure of tax money this really was

Phoenix has entered into exclusive negotiations to sell the city-owned Sheraton Grand Phoenix downtown hotel —the largest hotel in Arizona — for $255 million.

The city signed a letter of intent with TLG Phoenix LLC, an investment company based in Florida, to accept the offer and negotiate a purchase contract, city officials announced Tuesday evening.

But the deal faces criticism from some council members concerned about the loss to taxpayers. The city also attempted, unsuccessfully, to sell the hotel to the same buyer for a higher price last year.

If Phoenix ultimately takes the offer, the city's total losses on the taxpayer-funded Sheraton could exceed $100 million.

The city still owes $306 million on the hotel and likely would have to pay that off, even after a sale. That would come on top of about $47 million the city has sunk into the hotel, largely when bookings dropped due to the recession.

...

In addition to taking a loss on the building, Phoenix would give the buyer a property-tax break — the city hasn't released a potential value for that incentive — and transfer over a roughly $13 million reserve fund for hotel improvements.

By the way, the hotel -- after just 9 years under city ownership -- will require a $30 to $40 million face lift from the owner. Why do I suspect that part of the sales price problem is that the government, like with every other asset it owns, did not keep up with its regular maintenance?

Update: Phoenix is in the top ten US cities in terms of hotel room capacity, so city government of course detects that there is a market failure such that the city ... needs more hotel rooms, so it gets the government in the business of building more. Good plan.

Why SJW's Are the Worst Mystery Writers (Spoiler Alert: The Culprit is Always Racism)

A while back I wrote "Why haven't we heard any of these concerns? Because the freaking Left is no longer capable of making any public argument that is not based on race or gender."

A classic example of this is Nancy MacLean's new book Democracy in Chains. She has apparently detected the great conspiracy behind the modern Right, which according do her is a racist backlash against the civil rights movement. And the person at the heart of this conspiracy is... economist James Buchanan?

For those who don't know, which is probably most of the folks in this country, Buchanan won the Nobel Prize in economics for his development of public choice theory. If you are unfamiliar with this body of work, I encourage you to investigate it, but in short it analyzes government officials as self-interested and subject to all the same incentives as ordinary people. This is in contrast to highly idealized analyses that consider government agents as perfectly serving the public and judges proposed government actions by their stated goals, rather than their likely operations as run by real human beings. It was developed in part as a reaction to market critics who would cite real world issues in complex markets and compare them to idealized results of hypothetical government regulations. It tends to explain things like special interest politics, regulatory capture, cronyism, and rent-seeking much better than traditional, rosier theories of government. For example

So the Progressive Left tends to hate public choice theory. They have nearly infinite faith in government action and don't like to hear about its limitations. So it is not surprising that MacLean would write a thoughtful, scholarly critique of public choice theory, backed by a variety of economic evidence. HAH! Just kidding. This is 2017. Academics in the social sciences, mostly on the Left, don't operate that way. The only approach they know to refuting such a theory is to link it with racism. And so that is what she attempts. This is part of the summary from Amazon:

“[A] vibrant intellectual history of the radical right . . .” – The Atlantic

“This sixty-year campaign to make libertarianism mainstream and eventually take the government itself is at the heart of Democracy in Chains. . . . If you're worried about what all this means for America's future, you should be” – NPR

“Riveting” – O, The Oprah Magazine (Top 20 Books to Read This Summer)

An explosive exposé of the right’s relentless campaign to eliminate unions, suppress voting, privatize public education, and change the Constitution.

Behind today’s headlines of billionaires taking over our government is a secretive political establishment with long, deep, and troubling roots. The capitalist radical right has been working not simply to change who rules, but to fundamentally alter the rules of democratic governance. But billionaires did not launch this movement; a white intellectual in the embattled Jim Crow South did. Democracy in Chains names its true architect—the Nobel Prize-winning political economist James McGill Buchanan—and dissects the operation he and his colleagues designed over six decades to alter every branch of government to disempower the majority.

In a brilliant and engrossing narrative, Nancy MacLean shows how Buchanan forged his ideas about government in a last gasp attempt to preserve the white elite’s power in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education. In response to the widening of American democracy, he developed a brilliant, if diabolical, plan to undermine the ability of the majority to use its numbers to level the playing field between the rich and powerful and the rest of us.

Corporate donors and their right-wing foundations were only too eager to support Buchanan’s work in teaching others how to divide America into “makers” and “takers.” And when a multibillionaire on a messianic mission to rewrite the social contract of the modern world, Charles Koch, discovered Buchanan, he created a vast, relentless, and multi-armed machine to carry out Buchanan’s strategy.

Hah, this is the Progressive Left, so you just knew the Kochs had to be implicated as well. A couple of thoughts

- My first response is: if only. It would be fabulous if, say, the Republican Party was constructed on top of the work of Buchanan and public choice theory. Alas, it is not

- The links to racism the books rests on are simply a joke, but typical of the quality of public discourse today. You see it all the time. Coyote gave money to the Cato Institute. Joe Racist and Jane Hatemonger also gave money to Cato. So Coyote has been "linked" to these bad people, and therefor must believe everything they do.**

- Yet another in a long line of books about how libertarians are plotting to enslave you by devolving power to the individual and leaving you alone

- Don Boudreaux has been collecting a lot of links to critiques of the book. Beyond the silly vast-right-wing-conspiracy level of scholarship, apparently MacLean edited a lot of the key quotes she uses in the book to essentially reverse their meaning.