Posts tagged ‘art’

America's Soft Power We Don't Even Realize We Have

A while back I took at Teaching Company course on Victorian Great Britain. The professor said something about the Victorians that really stuck with me -- he said that the British never understood the soft power they had in the world. The world wanted to dress British and emulate British manners. They read British authors. They desperately wanted to send their children to British schools. Even the native revolutionaries in their colonies sometimes revolted in very British ways. Sure the leaders of the Indian National Congress harbored enormous resentments against the arrogance of British power, but all their leaders were British-schooled and cast many of their arguments in terms from the British enlightenment.

I was thinking about this a while back when I was in France and attended a show of local French artists. As with much modern art, much of it incorporated bits of pop culture. And about 98% of that was American and to a lesser extent British pop culture. Sure, some of it was used ironically, but American culture is consumed everywhere in the world. I must have seen 5 or 6 artists using Captain America imagery alone in their art in a not-at-all hostile or ironic way.. America in the 20th and 21st century is in the same position as the British in the 19th century, and we are probably just as unaware of that soft power and pissing it away just as surely with our slamming around the world like a bull in a china shop.

And speaking of China, it is simply insane in my mind to turn them into our enemies. Whatever the top Chinese officials are after, much of the population wants to be like Americans. They want to come to our schools and wear our fashions and watch our movies and TV. We have had several exchange students from China live with us and they treat getting to spend time living in America like having hit the lottery. We have watched one woman who goes by "Cat" in the US all the way from high school to college in America to getting a good banking job. She first showed up at our house looking exactly like Ching "Honey" Huan from Doonesbury -- the hair, glasses, clothes, everything. She now looks, dresses, and talks like any young American. For a while her Instagram was dominated by pictures of her and her friends at Big 10 football games.

I have been consumed of late with other things in my life, and really have not had the chance to address the increasingly insane extent of the Trump Administration's economic nationalism. But go to Don Boudreax's and Mark Perry's blogs and scroll through them -- they do a much more eloquent job of defending free trade than I can.

The Number One Worst Art Experience

A while back I wrote that the Mona Lisa was easily the most disappointing art experience of my life (I believe I put the viewing of Seurat's Grande Jatte on the other end as exceeding expectations.) If you are not sure why I dinged Da Vinci's lady so harshly, see this.

Watching this scene as she does every day, I now understand her smile.

Thinking About the College Admissions Bribery Scandal as Bootlegging Around A Cartel

In the college admissions bribery scandal that is unfolding (with almost certainly more to come), parents were willing to spend up to $500,000 for something whose list price is like $50 (ie the application fee). When I see this happen, I immediately think that there must be some sort of artificial shortage. After all, why wouldn't new suppliers jump into the market when such demand is apparently going unmet?

For years I have been pestering my alma mater to spend more of its endowment increasing capacity. For example, several years ago I wrote:

...the Ivy League needs to find a way to increase capacity. The number of kids that are "ivy-ready" has exploded over the last decades, but the class sizes at Ivy schools have remained flat. For years I have been campaigning at Princeton for this, and I am happy to see they are increasing the class size, but only by a small amount. Princeton has an endowment larger than the GNP of most countries. To date, it has spent that money both well and poorly. Well, because Princeton is one of just a handful of schools that guarantee that if you get in, they will make sure you can pay for it, and they do it with grants, leaving every student debt free at graduation. Poorly, because they have been overly focused on increasingly what I call the "educational intensity" or the amount of physical plant and equipment and stuff per student. In this latter case, we have got to be near the limit of spending an incremental $10 million to increase the education quality by .01%. We should instead be looking for ways to offer this very high quality of education to more people, since so many more are qualified today.

To illustrate this point I used this example in another post on the same topic

Let's say an Ivy has 5,000 students and a 10 point (on some arbitrary scale) education advantage over other schools. Let's consider two investments. One would increase their educational advantage by 10% from 10 to 11 (an increase I would argue that is way larger than the increase from investments they have recently made). The other investment would double the size of the school from 5,000 to 10,000 but let's say that through dilution and distraction it dropped the educational advantage by 10% from 10 to 9. The first investment adds something like 5,000 education points to the world (5,000 kids x 11 minus 5,000 kids x 10). The second adds 40,000 points to the world (10,000 x 9 minus 5,000 x 10). It's not even close. In fact, the expansion option is still favored even if the education advantage drops by 40%.

Here is a test. Quick: Name a well-known liberal arts college or university with a high academic reputation that was founded in the last 100 years. Tick tick. Give up? The only one I can come up with is Claremont-McKenna. When I started asking this question 10 years ago the answer also included Rice University, but it is now out of the window. Compare that to top art schools -- some like RISD go back to the 19th century but CalArts and ArtCenter are both less than 75 years old and probably the hottest current art school SCAD is less than 50 years old. SCAD is a great example. SCAD is growing like crazy -- it owns half of downtown Savannah, it seems -- and has a great reputation despite its youth and despite its admissions policies that are far less restrictive than other colleges or even other art schools. It is innovative and responsive to students in a way that few liberal arts colleges are. It has clearly tapped into a huge unmet demand. Why can't anyone do this in the liberal arts world??

The cynical view, which I lean towards more as I age, is that Ivy-type university degrees are all about signalling and not the education itself, and thus expansion just defeats the purpose because it dilutes the signalling value. For years when I met gung ho kids who were impressed that I went to Princeton and depressed that they likely would not, I would tell them that Princeton differed from their state school in this way: At your state school, you can get a really good education but you may have to work for it; if you choose to slack, you won't get it. In contrast, at an Ivy League school, you are going to get challenged whether you want to or not. At least that is what I used to say. I am not sure that is true any more of the Ivies, if it was ever true (I may have just been fooling myself). We used to use "went to college" as a synonym for "educated", but I think that relationship is gone. It's very clear you can go anywhere, Ivy League included, and fail to leave educated.

Some of my thinking on this was fast-forwarded given the experience of one of my kids. We had classic suburban expectations for our smart kids, and were proud our daughter got into a top 20 university. She really even then wanted to go to art school, but we worried she would end up living in a refrigerator box on the street with an art degree (well, not literally, but that was the family joke). But after a year she hated the university**. She did fine academically, but it wasn't what she wanted to do. And after she took the reigns and worked on a do-over for herself at art school, I started thinking a bit more about it. She works really hard at art school -- way harder than I or her brother worked in college -- and she is learning an actual craft that people value and pay for. She has a heck of a lot more prospects on graduating than the Brown grad who majored in Ecuadorian feminist poetry.

I don't want to be disingenuous here -- I traded on the value of my degrees and the schools they came from until I was 40 (after that I was running on my business and they became largely irrelevant, even a bit of a handicap). But when I think back on what I gained most in my education, I would list these three things first:

- The ability to clearly define a problem -- drawing a box around the system, defining inputs and outputs, etc

- The ability to write (some examples on this blog notwithstanding)

- The joy of learning -- at last count I have complete about 85 Teaching Company courses of an average 36 lectures each and 13 Pimsleur language courses of 30 lessons each.

By the way, if I had to define my main privilege in all of this, Princeton would not be first, because in fact I really developed the three above in a great private high school my parents were able to afford.

Postscript: Many have assumed these kids who got in fraudulently displaced some low income minority. I find that hard to believe, knowing how admissions offices work and the general philosophical outlook of universities. Much more likely that the marginal candidate cut was a midle class Asian-American.

** One of the interesting features of top schools is that it may be hard to get in, but they work to get every kid over the finish line. That is why the real credential of an Ivy League school is as much admission as graduation. To illustrate this, my daughter is in her third year at art school but her university she started at is still sending her emails saying that its not too late to come back.

Foxconn Not Only a Crony Capitalist but an Unreliable One To Boot

Who says that professional sports have nothing to teach businesses? Pro sports team owners have perfected the art of promising the world to local citizens to get taxpayers to pay for their billion dollar stadiums (which in the case of NFL teams are used approximately 30 hours a year). The Miami Marlins in particular have perfected the art of building a good team, leveraging its success to get a new stadium deal, and then immediately dismantling the team and buying cheap replacement players.

In the business world many corporations have taken the Miami Marlins strategy. Tesla took $3/4 of a billion dollars form NY taxpayers to build a factory in Western New York, only to employ a tiny fraction of the promised employees. In fact, one academic studied all the relocation subsidies NY has made in the recent past and found none of the gifted companies fulfilled their employment promises. In Mesa, AZ there is a factory that I call the graveyard of cronyism where not one but two sexy high-profile companies have gotten subsidies to move in (FirstSolar and Apple) only to both bail on their promises after banking the money.

So it should come as zero surprise that the Trump-facilitated crony Foxconn deal in Wisconsin is following the same path.

Foxconn Technology Group, a major supplier to Apple Inc., is backing down on plans to build a liquid-crystal display factory in Wisconsin, a major change to a deal that the state promised billions to secure.

Louis Woo, special assistant to Foxconn Chairman Terry Gou, said high costs in the U.S. would make it difficult for Foxconn to compete with rivals if it manufactured LCD displays in Wisconsin. In the future, around three-quarters of Foxconn’s Wisconsin jobs would be in research, development and design, he said.

They added this:

The company remains committed to its plan to create 13,000 jobs in Wisconsin, the company said in a statement.

Yeah, sure. Anyone want to establish a prop bet on this one? I will take the under.

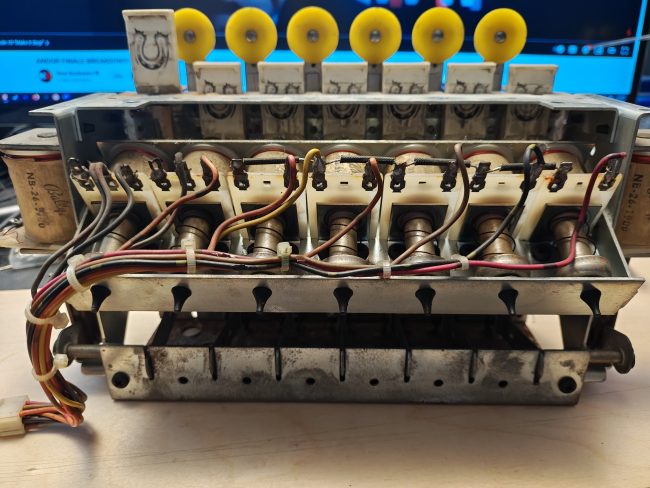

Recommendation: 99Designs

I am going to a trade show in a month or two. I bought one of the standard backdrop things and needed some art for it. I was quickly told that all my attempts looked like bad powerpoint slides transferred to the backdrop. So I tried a site called 99designs. They have a whole pool of freelance designers that compete for simple jobs - logos, wordpress templates, backdrop art, etc. I committed $250 to a design contest for my backdrop (the site takes some cut of that and the rest is a prize for the winner). That was 2 days ago. At this moment I have 35 different designs sitting there for me to comment on and choose from. Almost any one would be acceptable, and many are fabulous.

This strikes me as a classic victory for the division of labor. I am getting what seems like a crazy amount of good work for $250, work I could not duplicate myself for 100x that. I suspect that some of this stuff is super-derivative and is banged out using simple tools in just a few minutes, but so what? They can do something fast that I can't do at all and we all benefit.

My New Favorite Attraction in LA and it NEVER Gets Any Publicity

A couple of weeks ago my wife and I were in Pasadena and we visited the Huntington. I almost never see it on list of things to do in LA. This list has 22 things including some odd choices but no mention of the Huntington.

The Huntington is the mansion and grounds of one of the heirs to railroad magnate Collis P Huntington. Perhaps one of the reasons it is not well-known is that it is hard to exactly categorize what this place is. First, it is an amazing garden (pictures below) that has a desert garden, a tropical garden, a temperate garden, a Japanese garden, the bonsai garden, a Chinese garden, a water garden, a rose garden and an herb garden. I have been to a lot of gardens and arboretums around the world and this compares to the best. More enjoyable, for example, than either major arboretum in Singapore which top tourist lists. Then, there are the art museums, actually two. We only made it to the European art museum, which was in the original mansion -- it contained a lot of large portraiture by Sargent and Gainsborough, among other works. And then there is what is actually the centerpiece of the facility, the library. Only a small part of the collection is on display, but what is there is amazing -- from fabulous illuminated manuscripts to a Gutenberg Bible to a number of signature historical documents. As icing on the cake, there is the chance to walk through a couple of great mansions with a good part of the original furnishings intact.

The closest analog I can come up with is the Getty. The Getty gets top billing in many LA must-do lists, and I can tell you that the Huntington blows the Getty away. Sure, you should see the Getty, but I have never had a desire to go back. I will be back to the Huntington as soon as I can.

I could fill this post with pictures, but I will simply provide a few teasers:

NCAA: The World's Last Bastion of British Aristocratic Privilege

It is incredible to me that we still fetishize amateurism, which in a large sense is just a holdover from British and other European aristocracies. Historically, the mark of the true aristocrat was one who was completely unproductive. I am not exaggerating -- doing any paid work of any sort made one a tradesman, and at best lowered ones status (in England) or essentially caused your aristocratic credentials to be revoked (France).

The whole notion of amateurism was originally tied up in this aristocratic nonsense. It's fine to play cricket or serve in Parliament unpaid, but take money for doing so and you are out. This had the benefit of essentially clearing the pitch in both politics and sports (and even fields like science, for a time) for the aristocracy, since no one else could afford to dedicate time to these pursuits and not get paid. These attitudes carried over into things like the Olympics and even early American baseball, though both eventually gave up on the concept as outdated.

But the one last bastion of support of these old British aristocratic privileges is the NCAA, which still dedicates enormous resources, with an assist from the FBI, to track down anyone who gets a dollar when they are a college athlete. Jason Gay has a great column on this today in the WSJ:

This is where we are now, like it or not. College basketball—and college football—are not the sepia-toned postcards of nostalgia from generations past. They’re a multibillion dollar market economy in which almost everyone benefits, and only one valve—to the players—is shut off, because of some creaky, indefensible adherence to amateurism. Of course some money finds its way to the players. That’s what the details of this case show. Not a scandal. A market.

Don’t look for the NCAA to acknowledge this, however. “These allegations, if true, point to systematic failures that must be fixed and fixed now if we want college sports in America. Simply put, people who engage in this kind of behavior have no place in college sports,” NCAA president Mark Emmert said in a statement that deserved confetti and a laughing donkey noise at the end of it.

I am not necessarily advocating that schools should or should have to pay student athletes, though that may (as Gay predicts) be coming some day. But as a minimum the ban on athletes accepting any outside money for any reason is just insane. As I wrote before, athletes are the only students at a University that are not allowed to earn money in what they are good at. Ever hear of an amateurism requirement for student poets? For engineers?

When I was a senior at Princeton, Brooke Shields was a freshman. At the time of her matriculation, she was already a highly paid professional model and actress (Blue Lagoon). No one ever suggested that she not be allowed to participate in the amateur Princeton Triangle Club shows because she was already a professional.

When I was a sophomore at Princeton, I used to sit in my small dining hall (the now-defunct Madison Society) and listen to a guy named Stanley Jordan play guitar in a really odd way. Jordan was already a professional musician (a few years after he graduated he would release an album that was #1 on the jazz charts for nearly a year). Despite the fact that Jordan was a professional and already earned a lot of money from his music, no one ever suggested that he not be allowed to participate in a number of amateur Princeton music groups and shows.

My daughter is an art major at a school called Art Center in Pasadena (where she upsets my preconceived notions of art school by working way harder than I did in college). She and many, if not most of her fellow students have sold their art for money already, but no one as ever suggested that they not be allowed to participate in school art shows and competitions.

I actually first wrote about this in Forbes way back in 2011. Jason Gay makes the exact same points in his editorial today. Good. Finally someone who actually has an audience is stating the obvious:

In the shorter term, I like the proposals out there to eliminate the amateurism requirement—allow a college athlete in any sport (not just football or basketball) to accept sponsor dollars, outside jobs, agents, any side income they can get. The Olympics did this long ago, and somehow survived. I also think we’ll see, in basketball, the NBA stepping up and widening its developmental league—junking the dreadful one-and-one policy, lowering its age minimum, but simultaneously creating a more attractive alternative to the college game. If a player still opts to go to college, they’ll need to stay on at least a couple of seasons.

If you still think the scholarship is sufficient payment for an athlete in a high-revenue sport, ask yourself this question. There are all kinds of scholarships—academic, artistic, etc. Why are athletic scholarship recipients the only ones held to an amateurism standard? A sophomore on a creative writing scholarship gets a short story accepted to the New Yorker. Is he or she prohibited from collecting on the money? Heck no! As the Hamilton Place Strategies founder and former U.S. treasury secretary Tony Fratto succinctly put it on Twitter: “No one cares about a music scholarship student getting paid to play gigs.”

A Couple of Vegas Notes

Was in Vegas last week for a conference at the Cosmopolitan. A couple of notes:

- IMO the best bar in Vegas is the bar in the sky lobby of the Mandarin Oriental Hotel. Quiet, intimate, and with a drop-dead gorgeous view of the strip. Honestly, the picture in the link understates how dramatic the view is. Expensive drinks, of course, but the sliders they sell at the bar are excellent.

- Vegas is preparing itself for the sorts of terrorist attacks where trucks drive through crowded streets and sidewalks (the posts in the shrink-wrapping are all new). Seems like a reasonable precaution given the pedestrian numbers and their likely terrorist target ranking

- First time I have ever had a business meeting in a room with strippers on the carpet. Stay classy, Las Vegas. One attendee said "I am glad my HR director is not attending, she would probably call an alert and order an evacuation."

- Hey - a cigarette machine re-purposed to vend little bits of art.

The Teaching Company (Also Known as Great Courses)

A while back I was writing about something -- the Civil War I think -- and I mentioned that I had been lucky enough to have James McPherson as a professor. I remember a comment on the post that said something like "yes, yes we know, you went to Princeton." I certainly was lucky, and that school contributed a lot to what I am. But as far as attributing sh*t I know to a source, Princeton is in at least second place. By far the greatest source of what I know about history, art, music and even about the sciences comes from the Teaching Company. And that is available to all of you, no SAT required.

I just checked my account and I have taken 71 courses from them, including 54 history courses**. I think I have taken, for example, pretty much all the courses on this list in a Tyler Cowen post. I began my journey taking courses on things that had always interested me but I knew a fair amount about already, such as the history of Ancient Rome or the Civil War or WWII. But the most fun I have had has been taking courses on periods I knew little about -- such as Daileader's great histories of the Middle Ages or the History of China. And I have had the most fun taking courses on things I knew NOTHING about, such as the history of India, of pre-Columbian American civilization, and of nomadic civilizations of Asia.

The key thing to remember is: never pay rack rate. Everything goes on sale from time to time. Today until midnight, for example, they are having a 70% off sale on a subset of their stuff. You can still get cd's and dvd's if you want but I used to get the digital download for my iPod and increasingly just stream the audio from an android app and stream the video from their Roku app.

** My family thinks I am weird because I listen to these courses as I run and work out (instead of music). But it turns out this was not nearly as weird as when I have done Pimmsleur language courses while I am running. If you want to really take your mind off your running, try to diagram a sentence in your head to figure out which of freaking German article you should be using. Also, it creates a nice reputation around the neighborhood for eccentricity if you babble in foreign languages as you run.

More NCAA Discrimination Against Athletes With Stupid Amateurism Rules

When I was a senior at Princeton, Brooke Shields was a freshman. At the time of her matriculation, she was already a highly paid professional model and actress (Blue Lagoon). No one ever suggested that she not be allowed to participate in the amateur Princeton Triangle Club shows because she was already a professional.

When I was a sophomore at Princeton, I used to sit in my small dining hall (the now-defunct Madison Society) and listen to a guy named Stanley Jordan play guitar in a really odd way. Jordan was already a professional musician (a few years after he graduated he would release an album that was #1 on the jazz charts for nearly a year). Despite the fact that Jordan was a professional and already earned a lot of money from his music, no one ever suggested that he not be allowed to participate in a number of amateur Princeton music groups and shows.

My daughter is an art major at a school called Art Center in Pasadena (where she upsets my preconceived notions of art school by working way harder than I did in college). She and many, if not most of her fellow students have sold their art for money already, but no one as ever suggested that they not be allowed to participate in school art shows and competitions.

A football player for the University of Central Florida has lost his place in the team, and hence his scholarship, due to his YouTube channel. UCF kicker Donald De La Haye runs "Deestroying," which has over 90,000 subscribers and has amassed 5 million views, thus far. It's not the channel itself that cost him his scholarship, though -- it's the fact that he has athletics-related videos on a monetized account.

The NCAA saw his videos as a direct violation to its rule that prohibits student athletes from using their status to earn money. UCF's athletics department negotiated with the association, since De La Haye sends the money he earns from YouTube to his family in Costa Rica. The association gave him two choices: he can keep the account monetized, but he has to stop referencing his status as a student athlete and move the videos wherein he does. Or, he has to stop monetizing his account altogether. Since De La Haye chose not to accept either option, he has been declared inelegible to play in any NCAA-sanctioned competition, effectively ending his college football career.

When I was a sophomore at Princeton, my sister was a Freshman. We were sitting in my dorm the first week of school, watching US Open tennis as we were big tennis fans at the time. My sister told me that she still had not heard from her fourth roommate yet, which was sort of odd. About that time, the semifinals of the US Open were just beginning and would feature an upstart named Andrea Leand. My sister says, hey -- that's the name of my roommate. And so it was. Andrea was a professional tennis player, just like Brook Shields was already a professional actress and Stanley Jordan was already a professional musician. But unlike these others, Andrea was not allowed to pursue her talent at Princeton.

I don't know if student athletes should be paid by the school or not. We can leave that aside as a separate question. People of great talent attend universities and almost all of them -- with the exception of athletes -- are allowed to monetize that talent at the same time they are using it on campus. Athletes should have the same ability.

Postscript: I wrote about this years ago in Forbes. As I wrote there:

The whole amateur ideal is just a tired holdover from the British aristocracy, the blue-blooded notion that a true "gentleman" did not actually work for a living but sponged off the local [populace] while perfecting his golf or polo game. These ideas permeated British universities like Oxford and Cambridge, which in turn served as the model for many US colleges. Even the Olympics, though, finally gave up the stupid distinction of amateur status years ago, allowing the best athletes to compete whether or not someone has ever paid them for anything.

In fact, were we to try to impose this same notion of "amateurism" in any other part of society, or even any other corner of University life, it would be considered absurd. Do we make an amateur distinction with engineers? Economists? Poets?...

In fact, of all the activities on campus, the only one a student cannot pursue while simultaneously getting paid is athletics. I am sure that it is just coincidence that athletics happens to be, by orders of magnitude, far more lucrative to universities than all the other student activities combined.

Finally, Passing the Mantle of Responsibility to the Next Generation

Years ago I got tired of store-bought cards and cards with pictures of the family taken at Disneyland or skiing or whatever, so I created my own holiday card. We got positive feedback, so I did another (past examples here, here, here). I kept on with it, though over time it became a burden -- the weight of it would hit me about November 15: What am I going to do next year for a card?

But this year my daughter, who is off to art college in Pasadena this January, picked up the mantle and drew our family portrait for our card. Wow, what a relief. I feel like a tired 16th century farmer whose son just grew old enough to do the plowing.

So Merry Christmas, or happy whatever holiday you celebrate this time of year.

PS -- OK, I don't want to nitpick, but I guess the 16th century farmer probably criticized the straightness of his son's furrows. She made the drawing square, which necessitated a square envelope, which in turn cost us 20 cents extra in postage for each since square letters take special handling at the post office. But it was a small price to pay.

Update: To the comment that the choice of 16th century for my farmer analogy was sort of random, I happened at the time to be listening to yet another in the Great Courses series (love them) and it was just discussing agrigulture in the 16th century.

Southern California Real Estate Question

A few months ago I helped my son shop for an apartment in San Diego, where he is working for Ballast Point Beer. Currently I am helping my daughter look for apartments in Pasadena, where she may be attending art school. In both cases we found that small studio apartments often have higher rents than one- and sometimes even two-bedroom apartments in the same complex (and with the same fit and finish, amenities, etc.)

What the hell? I understand that there may be more demand for studio apartments in these neighborhoods among young singles than for larger apartments, but once one sees the studio for $2200 and the one-bedroom for $1800, why would one still choose the studio, which might be half the size? Ease of cleaning? Is there some artificial demand from some government or financial aid program that will only pay for studio apartments? Do Chinese students come to the US and suddenly get agoraphobia from an apartment that is too large?

The MPAA Responds, Urges that Taxpayers Continue Paying for Their Movie Productions

The MPAA wrote me back in response to my post here thanking our local paper for actually considering (for the first time I have ever seen locally) that subsidizing movie production locally might not be a good idea. The MPAA sent me a response, which in full is online here.

I will state in general that the whole academic sub-field of making net economic contribution calculations (always full of fact juicy multipliers) is a total write-off in my mind. You can pretty much throw out everything you read as crap. Because most are funded by the folks (e.g. sports team owners) who want the subsidy, so the analyses almost always miss the unseen: Here are all the job gains and benefits in our industry! But these studies almost always miss the opportunity cost effect of taking tax money and revenues from other industries. Besides, I truly believe the economy is far too complicated to pull out one single variable out of billions and forecast changes to overall economic numbers from changes in that single variable.

Here is the email I wrote back:

Sorry, but all industry-specific government subsidies are a total useless gravy train for the politically-connected industries that are able to obtain them.

- These state subsidies are only shifting jobs from state to state. Why should Americans be paying taxes just to move companies to different places around the country?

- The implication is that somehow your jobs you provide are better than the jobs my company provides, since you get taxpayer money handed to you and I don't. Why? Can you really make an academic argument that your multiplier of your jobs is somehow higher than my employees' multiplier? Your jobs last 3 months or so in my state, and the highest skilled and highest paid jobs go to people who travel only temporarily in from out of state. My jobs in my company have lasted for over 25 years. Remember -- you are essentially demanding that I be forced to pay money from my business to yours.

- Markets do a really good job of allocating capital. No industry, I suppose, feels like investors give them all they deserve. But what you are doing in effect is demanding that the market's allocation of capital be interrupted, and capital that would have been used for other purposes should be forced to be used for your purposed instead. What basis do you have for claiming this? And do your analyses ever consider the opportunity cost of what that tax money you are using would have been used for if it were not grabbed away for you?

- Your problem is basically that your movies don't make enough money on their own to cover costs and you need taxpayers to make up the difference. After all, you are arguing that less activity would occur without these subsidies so these subsidies must be the difference between losing and making money (and thus between greenlighting and turning down certain projects). To which I would provide a suggestion -- you need to do what all the rest of us business owners who don't have access to Uncle Sugar's money spigots must do when revenues don't cover costs: Fix your costs or increase your revenues. Make better movies or get your costs under control. Don't demand that I, as a taxpayer, have to make up the difference because you are too lazy or greedy to fix your own financial problems.

- I can't prove it, but I am not at all convinced subsidies make more movies. I think that subsidies tend to just increase the income of those in the movie production chain with the most bargaining power, such as actors and producers. This certainly is what has happened with sports subsidies. We insanely subsidize every pro sports team in America. Do you really think we would have fewer pro sports teams without the subsidies? No -- the subsidies have simply flowed to increasing the income of the top athletes and team owners.

At the end of the day, your industry is particularly good at getting this money forced out of taxpayer hands for two reasons. The first is that politicians hope for financial support from you in the next election. Hell, you might even convince me that local small-time politicians do it entirely just for a photo op with some actor or celebrity. And the second is that you make for a sexier press release. Politicians like saying they funded Apple or Tesla or highbrow art like "Sausage Party" -- it makes for a better soundbite in their campaigns than saying they funded a call center or a machine shop.

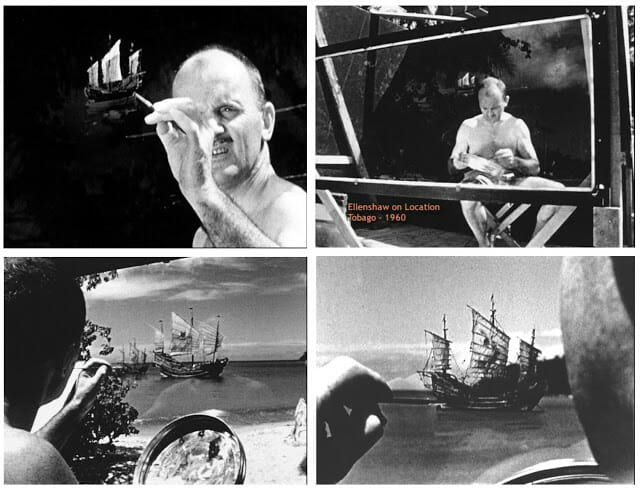

Before There Was Green Screen

People act as if it is something new and different when actors shoot scenes and 95% of the space on the screen is later filled in by CGI. This has actually been going on for decades with matte paintings on glass. Movie scenes were either filmed directly through the glass (there are some great examples in the linked article with Disney artists painting sailing ships on a bay for filming) or reshot later by projecting the original film and reshooting it with the matte art.

Here is a an example before and after the painted matt. Just like CGI, only CGI can add movement and dynamic elements

I had thought all this stuff was done in post production but apparently Disney at least shot a lot of scenes straight through a matte. I love this guy, sitting on the beach painting ships on glass so they would be sitting on the bay in the scene. You can almost imagine the actors tapping their feet waiting for him to be finished.

Much of the beauty of the original Star Wars movie was in its great matte paintings, not only of planets but of the large Death Star interior scenes.

If Westerners can't do yoga and Cinco de Mayo parties, can we have our polio vaccines back?

With news that even yoga classes are being cancelled due to fears of Westerners appropriating from other cultures, I am led to wonder -- why don't these prohibitions go both ways? If as a white western male, I can't do yoga or host a Cinco de Mayo party or play the blues on the guitar, why does everyone else get to feed greedily from the trough of western culture? If I can't wear a sombrero, why do other cultures get to wear Lakers jerseys, use calculus, or even have polio vaccines? Heck, all this angst tends to occur at Universities, which are a quintessentially western cultural invention. Isn't the very act of attending Harvard a cultural appropriation for non-Westerners?

I say this all tongue in cheek just to demonstrate how stupid this whole thing is. Some of the greatest advances, both of science and culture, have occurred when cultures cross-pollinate. I have read several auto-biographies of musicians and artists and they all boil down to "I was exposed to this art/music from a different culture and it sent me off in a new direction." The British rock and roll invasion resulted from American black blues music being dropped into England, mutating for a few years, and coming back as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

Or here is an even better example: the movie"A fistful of Dollars". That was an American western with what has become a quintessentially American actor, Clint Eastwood. However, it was originally an Italian movie by Italian director Sergio Leone (it was not released in the US until 3 years after its Italian release). But Sergio Leone borrowed wholesale for this movie from famed Japanese director Akiro Kurosawa's Yojimbo. But Kurosawa himself often borrowed from American sources, fusing it with Japanese culture and history to produce many of his famous movies. While there is some debate on this, Yojimbo appears to be based on Dashiell Hammett's Red Harvest, a classic of American noir fiction.

Hey, I Love Eating Alone in Public

There are few things I enjoy more when I am on the road alone or even at home with my family gone for some reason than going to a nice restaurant, sitting at the bar, and having a few drinks and dinner. All by myself (OK, maybe with my Kindle too).

My favorite right now is the bar at Eddie V's steakhouse.

As a weird aside which I cannot explain, I am a pretty severe introvert who finds it almost impossible to make conversation with strangers at cocktail parties or at nearly any other venue. This week my wife and I were walking up Canyon Road in Santa Fe looking at art galleries and I just plain stopped going in because I didn't want to deal with the way every gallery salesperson tends to immediately overwhelm one with small talk. I worked long and hard to find a hair cutter and a dental hygenist that didn't insist on trying to have a conversation while they did their work on me. But despite all this, I can comfortably meet and interact with people while sitting at bars. Not sure why.

So Given My German Ancestry, Is Anything Beyond Wearing Lederhosen and Invading France Cultural Appropration?

I will say that this story honestly loses me.

Just when you think we’ve reached Peak Sensitivity, the scolds of social justice sprinkle more sand into their underpants. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston is currently showing a superb exhibition of the art of Hokusai. As per common practice at scholarly institutions, it is displaying related material, including an exhibition of contemporary Japanese photographers responding to the devastating earthquake that hit the northern part of the country in 2011. It also rehung La Japonaise, an 1876 canvas in its collection by Claude Monet, depicting his wife Camille in a vermillion kimono.

Among the educational programming at the MFA was “Kimono Wednesdays,” an opportunity for museumgoers to try on replica of that kimono in the presence of Monet’s canvas. It was slated for Wednesday evenings, when the museum’s entrance fee is by donation, starting June 24 and running throughout the month of July. But it didn’t make it that far.

Demonstrators showed up at the first two events bearing posters accusing the participants of grave wrongdoing. “Try on the kimono; learn what it’s like to be a racist imperialist today!” exclaimed one. “Let’s dress up Orientalism with more Orientalism,” read another. The protest had been arranged through a Facebook group named Stand Against Yellow-Face @ the MFA (the discussions have moved to a Tumblr), where the principals and their supporters expressed great umbrage. “A willingness to engage in thoughtful dialogue (or not) with museum employees and visitors on the bullshit of this white supremacist ‘costume’ event are welcome,” wrote one of the organizers.

Eventually the museum caved and even apologized. I can understand the caving -- as the author suggested, it simply was not a hill the museum needed to die on -- but these apologies for non-crimes have got to stop. Someone has to show some backbone in the face of these absurd pogroms.

When my family was visiting castles in England, they often had clothes for the kids to play dress-up in medieval garb. When my son and his friends were at Octoberfest, they bought lederhosen to wear when they attended. When I took Spanish for years in grade school, we often did projects that emulated various Spanish cultures we were studying (such as the Mexican tradition of leaving out decorated shoes for candy and gifts). Are these all wrong now?

I suppose if the museum had a "dress like a Kamikaze pilot" promotion or "pretend to be a comfort girl" exhibit, I could see the problem. But trying on a kimono? Kimono's have gone through several cycles of being fashionable in the West over the last 200 years or so (in the James Bond books, Ian Fleming often noted that Bond preferred a kimono for sleeping).

Seriously, we Americans have little in the way of home grown culture - haven't we appropriated about everything? And so what? The opposite of cultural appropriation in my mind is cultural apartheid. Which in fact seems to be what some progressives are advocating for on campus, coming full-circle and apparently asking for separate but equal facilities for women and certain ethnic groups so they won't be tainted by white maleness, or whatever.

I Never Listen to Democrats; I Learned Everything I Need To Know About them From Rush Limbaugh

One of my huge pet peeves is when people rely only on their own side for knowledge of their opponents' positions. The inevitable result of this is that there is a lot of debating against straw men.

As an aside, this is why I really like Bryan Caplan's ideological Turing test. If you are going to seriously debate someone, you need to be able to state their arguments in an unironic way such that that person's supporters would mistake you for one of their own. If I were to teach anything at all political, I would structure the course in a way that folks would debate and advocate both sides of a question (that is, of course, if any university would allow me to ask, say, a minimum wage advocate to take the opposite position without accusing me of creating an unsafe environment).

Anyway, a while back I asked if the folks who were protesting the showing of American Sniper on campus had actually seen the damn movie. I suspected they had not, or at least really interpreted film differently than I do. Though perhaps pro-soldier, I read the movie as having a pretty stark anti-war message.

Anyway, American Sniper has become a favorite target for banning within our great universities the purport to be teaching critical thinking. This is from one student group's (successful) appeal for a ban on showing the movie on campus:

This war propaganda guised as art reveals a not-so-discreet Islamaphobic, violent, and racist nationalist ideology. A simple Google search will give you hundreds of articles that delve into how this film has fueled anti-Arab and anti-Islamic sentiments; its visceral "us verses them" narrative helps to proliferate the marginalization of multiple groups and communities - many of which exist here at UMD.

This is not the language people would use if they had actually seen the film. Instead of taking specific examples from the film, they refer to Google searches of articles, perhaps by other people who have not seen the film (as an aside, this has to be the all-time worst appeal to authority ever -- I can find not hundreds but thousands of articles on the Internet about anything -- there are tens of thousands alone on the moon landings being faked).

Why Large Corporations Often Secretly Embrace Regulation

I wrote the other day about how Kevin Drum was confused at why broadband stocks might be rising in the wake of news that the government would regulate broadband companies as utilities. I argued the reason was likely because investors know that such regulation blocks most innovation-based competition and tends to guarantee companies a minimum profit -- nothing to sneeze at in the Internet world where previous giants like AOL, Earthlink, and Mindspring are mostly toast.

James Taranto pointed today to an interesting Richard Eptstein quote along the same lines (though he was referring to hospitals under Obamacare):

Traditional public utility regulation applies to such services as gas, electric and water, which were supplied by natural monopolists. Left unregulated, they could charge excessive or discriminatory prices. The constitutional art of rate regulation sought to keep monopolists at competitive rates of return.

To control against the risk of confiscatory rates, the Supreme Court also required the state regulator to allow each firm to obtain a market rate of return on its invested capital, taking into account the inherent riskiness of the venture.

Avoiding McDonald's

Watching the Superbowl, and seeing the McDonald's commercial where the company announced a policy that they will ask their customers to do various kinds of performance art rather than pay, I said to my kids, "well, I guess I am avoiding McDonald's for a while." Not only do I not want to sing a song to avoid paying my $5 bill, I probably would pay them $50 to shut up and just give me my damn food.

My kids acted like I was being a curmudgeon, but apparently I am not alone:

Early on Monday morning I paid a visit to the Golden Arches while traveling through Union Station in Washington, D.C. After a moment’s wait I placed my order with an enthusiastic cashier, and started to pay.

Suddenly the woman began clapping and cheering, and the restaurant crew quickly gathered around her and joined in. This can’t be good, I thought, half expecting someone to put a birthday sombrero on my head. The cashier announced with glee, “You get to pay with lovin ’!” Confused, I again started to try to pay. But no.

I wouldn’t need money today, she explained, as I had been randomly chosen for the store’s “Pay with Lovin’ ” campaign, the company’s latest public-relations blitz, announced Sunday with a mushy Super Bowl TV commercial featuring customers who say “I love you” to someone, or perform other feel-good stunts, and are rewarded with free food. Between Feb. 2 and Valentine’s Day, the company says, participating McDonald’s locations will give away 100 meals to unsuspecting patrons in an effort to spread “the lovin’.”

If the “Pay with Lovin’ ” scenario looks touching on television, it is less so in real life. A crew member produced a heart-shaped pencil box stuffed with slips of paper, and instructed me to pick one. My fellow customers seemed to look on with pity as I drew my fate: “Ask someone to dance.” I stood there for a mortified second or two, and then the cashier mercifully suggested that we all dance together. Not wanting to be a spoilsport, I forced a smile and “raised the roof” a couple of times, as employees tried to lure cringing customers into forming some kind of conga line, asking them when they’d last been asked to dance.

The public embarrassment ended soon enough, and I slunk away with my free breakfast, thinking: Now there’s an idea that never should have left the conference room.

It didn't look touching on TV, it looked awful. I had already decided to avoid McDonald's for the time being based on the commercial but my thanks to the author for confirming it.

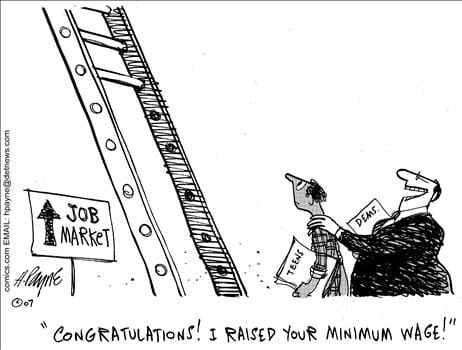

The Great Class of 1984

One of the great joys of being in Princeton's class of 1984 is having master cartoonist (and libertarian, though I don't know what he would call himself) Henry Payne in our class. For the last 30 years, Henry has made a custom birthday card for the class, which are mailed to each of us on the appropriate day. This is mine from 2014

I started saving these a while back but I wish I had saved all 30. I also have a caricature of me drawn in college by Henry, but it does not get a prized place on our wall at home because it includes my college girlfriend as well, which substantially reduces its value as perceived by my wife. (In speaker-building there is a common term of art called "wife acceptance factor" or WAF. Pictures of ex-girlfriends have low WAF).

Here is an example of some of Henry's great political work:

College Tours Summarized in One Sentence

The WSJ has an editorial on college tours, wherein they talk about the sameness (and lameness) of most college tours.

Most colleges offer both an information session and a tour. We always found the tour, given by students, more useful than information sessions given by the admission department. I came to hate the information sessions in large part because the Q&A seems to be dominated by type A helicopter parents worried that Johnny won't get into Yale because he forgot to turn in an art project in 3rd grade.

My kids and I developed a joke a couple of years ago about information sessions, in which we summarize them in one sentence. So here it is:

"We are unique in the exact same ways that every other college you visit says they are unique."

Examples: We are unique because we have a sustainability program, because we have small class sizes, because our dining plans are flexible, because we don't just look at SAT scores in admissions, because our students participate in research, because our Juniors go abroad, etc. etc.

There you go. You can now skip the information session and go right to the tour. Actually, there is a (very) short checklist of real differences. The ones I can remember off hand are:

- Does the school have required courses / distribution requirements or not

- Is admissions need blind or not

- Is financial aid in the form of grants or loans

- Do they require standardized tests or not, and which ones

- If they do, do they superscore or not

- Do they use the common app, and if so do they require a supplement

- Do they require an interview or not

My advice for tour givers (and I can speak from some experience having gone on about 20 and having actually conducted them at my college) is to include a lot of anecdotes that give the school some character. I particularly remember the Wesleyan story about Joss Whedon's old dorm looking out over a small cemetery and the role this may have played in the development of Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

The biggest fail on most tours is many don't show a typical dorm room, the #1 thing the vast majority of prospective admits want to see.

The Right To Not Be Offended

I already wrote about the Wellesley art kerfuffle, but I liked this quote form Lenore Skenazy

Once we equate making people feel bad with actually attacking them, free expression is basically obsolete, since anything a person does, makes or says could be interpreted as abuse.

Beyond the general amazing sight of feminists acting like Victorian women with the vapors rather than strong, confident human beings, I am still amazed at this interpretation of the art as somehow representing a male threat. Perhaps this is one area where the campus is poorer for the lack of male voices. I can't imagine there are many men who see this statue as anything other than a representation of fear and vulnerability and helplessness. Seriously, does anyone consider sleepwalking at school in your tighty whities as anything but a bad dream? If you had showed me this statue before all the brouhaha and asked me if it was more threatening to men or women, I would have answered "men" without a second thought.

Notes from the Cloister

I have read the petitions, and I still cannot understand why so many of the (all female) students of Wellesley College are having a major freak-out about this piece of sculpture. This is from a student petition to have it removed:

On contrary, this highly lifelike sculpture has, within just a few hours of its outdoor installation, become a source of apprehension, fear, and triggering thoughts regarding sexual assault for many members of our campus community. While it may appear humorous, or thought-provoking to some, it has already become a source of undue stress for many Wellesley College students, the majority of whom live, study, and work in this space.

Seriously? It's a freaking sculpture. I had thought that the whole point of women's colleges was to focus on creating strong, empowered women. My wife always felt that way about Vassar (where the culture of educating strong women apparently existed even after it went coed). But this story tells me that women's colleges have become cloisters to protect hothouse flowers whose fragile sensibilities can't handle a piece of art that is not particularly racy or outré (in the context of today's standards). This is taking the fake campus right to not be offended and turning it into a pathology. If you think I am exaggerating, go to the linked article and read the students and alums quoted.

To me, this art tells a story of a man's vulnerability and helplessness. I would have thought the feminists would have loved it.