A number of readers have written me, the gist of the emails being "you have written that X or Y is NOT causing higher oil prices -- what do you think IS causing high oil prices?" Well, OK, I will take my shot at answering that question. Note that I have a pretty good understanding of economics but I am not a trained economist, so what follows relates to hard-core economics in the same way pseudo-code relates to C++.

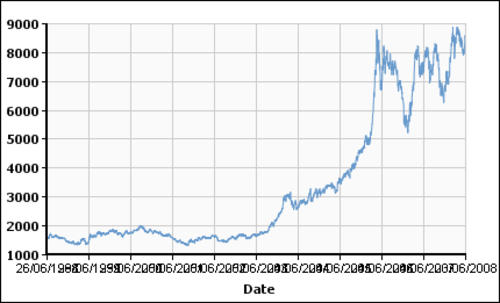

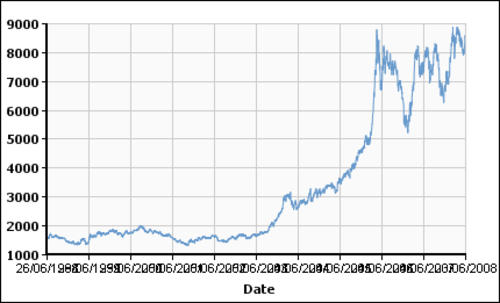

My first thought, even before getting into oil, is that commodity prices can be volatile and go through boom-bust periods. Here, for example, is a price chart of London copper since 1998:

While oil prices have gone up by a factor of about four since 1998, copper has gone up by a factor of about 15! But the media seldom writes about it, because while individual consumers are affected by copper prices, they don't buy the commodity directly, and don't have stores on every street corner with the prices posted on the street.

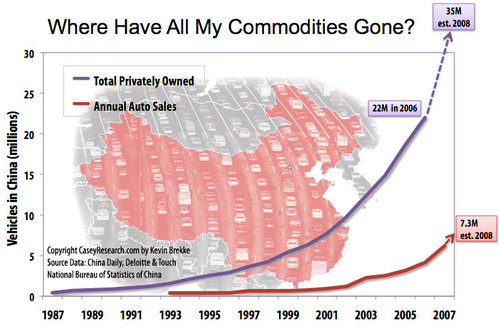

For a number of years, it is my sense that oil demand has risen faster than supply capacity. This demand has come from all over -- China gets a lot of the press, but even Europe has seen increases in gasoline use. Throughout the world, we are on the cusp of something amazing happening - a billion or more people in Asia and South America are emerging from millennia of poverty. This is good news, but wealthier people use more energy, and thus oil demand has increased.

On the supply side, my sense is that the market has handled demand growth up to a point because for years there was some excess capacity in the system. The most visible is that OPEC often has been producing below their capacity, with Saudi Arabia as the historic swing producer. But even in smaller fields in the US, there are always day to day decisions that can affect production and capacity on a micro scale.

One thing that needs to be understood - for any individual field, it is not always accurate to talk about its capacity or even its "reserves" as some fixed number. How much oil that can be pumped out on any given day, and how much total oil can be pumped out over time, depend a LOT on prices. For example, well production falls over time as conditions down in the bottom of the hole deteriorate (think of it like a dredged river getting silted up, though this is a simplification). Wells need to be reworked over time, or their production will fall. Just the decision on the timing of this rework can affect capacity in the short term. Then, of course, there are numerous investments that can be made to extend the life of the field, from water flood to CO2 flood to other more exotic things. So new capacity can be added in small increments in existing fields. A great example is the area around Casper, Wyoming, where fields were practically all shut-in in the 1990's with $20 oil but now is booming again.

At some point, though, this capacity is soaked up. It is at this point that prices can shoot up very rapidly, particularly in a commodity where both supply and demand are relatively inelastic in the short term.

Let's hypothesize that gas prices were to double this afternoon at 3:00PM from $4 to $8. What happens in the near and long-term to supply and demand?

In the near term, say in a matter of days, little will change on the demand side. Everyone who drove to work yesterday will probably drive today in the same car -- they have not had time to shop for a new car or investigate bus schedules. Every merchandise shipper will still be trucking their product as before - after all, there are orders and commitments in place. People will still be flying - after all, they don't care about fuel prices, they locked their ticket price in months ago.

However, people who argue that oil and gas demand is inelastic in the medium to long term are just flat wrong. Already, we are seeing substantial reductions in driving miles in this country due to gas price increases. Demand for energy saving investments, from Prius's to solar panels, is way up as well, demonstrating that prices are now high enough to drive not only changed behaviors but new investments in energy efficiency. And while I don't have the data, I am positive that manufacturers around the world have energy efficiency investments prioritized much higher today in their capital budgets.

There are some things that slow this demand response. Certain investments can just take a long time to play out. For example, if one were to decide to move closer to work to cut down on driving miles, the process of selling a house and buying a new one is lengthy, and is complicated by softness in the housing markets. There are also second tier capacity issues that come into play. Suddenly, for example, lots more people want to buy a Prius, but Toyota only has so much Prius manufacturing capacity. It will take time for this capacity to increase. In the mean time, sales growth for these cars may be slower and prices may be higher. Ditto solar panels.

Also, there is an interesting issue that many consumers are not yet seeing the full price effects of higher oil and gas prices,and so do not yet have the price incentive to switch behavior. One example is in air travel. Airlines are hedged, at least this year, against much of the fuel price increase they have seen. They are desperately trying not to drive people out of air travel (though DHS is doing its best) and so air fares have not fully reflected fuel price increases. And since many people buy their tickets in advance, even a fare increase today would not affect flying volumes for a little while.

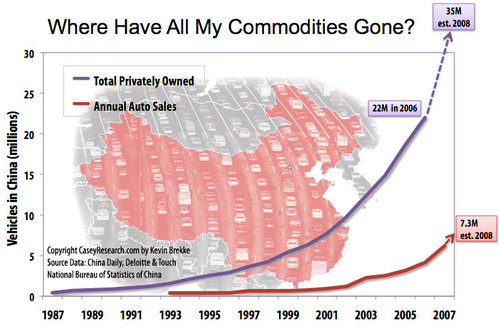

Another such example that is probably even more important are countries where consumers do not pay world market prices for gas and oil, with prices subsidized by the government (this is mostly true in oil producing countries, where the subsidy is not a cash subsidy but an opportunity cost in terms of lost revenue potential). China is perhaps the most important example. As we mentioned earlier, Chinese demand increases have been a large impact on world demand, as illustrated below:

All of these new consumers, though, are not paying the world market price for gasoline:

While consumers in much of the world have been reeling from spiraling

fuel costs, the Chinese government has kept the retail price of

gasoline at about $2.60 a gallon, up just 9% from January 2007.

During that same period, average gas prices in the U.S. have surged

nearly 80%, to about $4 a gallon. China's price control is great for

people like Tang, who drives long distances in his gas-guzzling Great

Wall sports utility vehicle.

But

Tang and millions of other Chinese are bracing for a big jump in pump

prices. The day of reckoning? Everybody believes it's coming right

after the Summer Olympics in Beijing conclude in late August.

Demand, of course, is going to appear inelastic to price increases if a large number of consumers are not having to pay the price increases.

Similarly, there are factors on the supply side that make response to large price increases relatively slow. We've already discussed that there are numerous relatively quick investments that can be made to increase oil production from a field, but my sense is that most of these easy things have been done. Further increases require development of whole new fields or major tertiary recovery investments in existing fields that take time. Further, we run up against second order capacity issues much like we discussed above with the Prius's. Currently, just about every offshore rig that could be used for development and exploration is being used, with a backlog of demand. To some extent, the exploration and development business has to wait for the rig manufacturing business to catch up and increase the total rig capacity.

There are also, of course, structural issues limiting increases in oil supply. In the west, increases in oil supply are at the mercy of governments that are schizophrenic. They know their constituents are screaming about high oil prices, but they have committed themselves to CO2 reductions. They know that their CO2 plans actually require higher, not lower, gas prices, but they don't want the public to understand that. So they demagogue oil companies for high gas prices, while at the same time restricting increases in oil supply. As a result, huge oil reserves in the US are off-limits to development, and both the US and Canada are putting up roadblocks to the development of our vast reserves of shale oil.

Outside of the west, most of the oil is controlled by government oil companies that are dominated by incompetence and corruption. For years, companies like Pemex have been under-investing in their reserves, diverting cash out of the oil fields into social programs to prop up their governments. The result is capacity that has not been well-developed and institutions that have only limited capability to ramp up the development of their reserves.

One of the questions I get asked a lot is, "Isn't there a good reason for suppliers to hold oil off the market to sustain higher prices?" Well, let's think about that.

Let's begin with an analogy. Why wouldn't Wal-mart start to hold certain items off the market to get higher prices? Because they would be slaughtered, of course. Many others would step in and fill the void, happy to sell folks whatever they need and taking market share from Wal-mart in the process. I think we understand this better because we know the players and their motivations better in retail than we do in oil. But the fact is that Wal-mart arguably has more market power, and in the US, more market share than any individual oil producer has worldwide. Oil producers have seen boom and bust cycles in oil prices for over a hundred years. They know from experience that $130 oil today may be $60 oil a year from now. And thus holding one's oil off the market to try to sustain prices only serves to miss the opportunity to get $130 for one's oil for a while. People tend to assume that the selfish play is to hold oil off the market to increase prices, but in fact it is just the opposite. The player who takes this strategy reduces his/her own profit in order to help everyone else.

This is a classic prisoner's dilemma game. Let's consider for a moment that we are a large producer with some ability to move prices with our actions but still a minority of the market. Consider a game with two players, us and everyone else. Each player can produce 80% of their capacity or 100%. A grid showing reasonable oil price outcomes from these strategies is shown below:

Reductions in our production from 100% to80% of capacity increases market prices, but not by as much as would reductions in production by other producers, who in total have more capacity than we. Based on these prices, and assuming we have a million barrels a day of production capacity, the total revenue outcomes for us of these four combinations are shown below, in millions of dollars (in each case multiplying the price times 1 million barrels times the percent production of capacity, either 80 or 100%):

We don't know how other producers will behave, but we do know that whatever strategy they take, it is better for us to produce at 100%. If we really could believe that everyone else will toe the line, then everyone at 80% is better for us than everyone at 100% -- but players do not toe the line, because their individual incentive is always to go to 100% production. For smaller players who do not have enough volume to move the market individually (but who make up, in total, a lot of the total production) the incentive is even more dramatically skewed to producing the maximum amount.

The net result of all this is that forces are at work to bring down demand and bring supply up, they just take time. I do think that at some point oil prices will fall back out of the hundreds. Might this reckoning be pushed backwards a bit by bubble-type speculation? Sure. People have an incredible ability to assume that current conditions will last forever. When oil prices were at $20 for a decade or so, people began acting like they would stay low forever. With prices rising rapidly, people begin acting like they will continue rising forever. Its an odd human trait, but a potentially lucrative one for contrarians who have the resources and cojones to bet against the masses and stick with their bet despite the fact that bubbles sometimes keep going up before they come back down.

I don't have the economic tools to say if such bubble speculation is going on, or what a clearing price for oil might be once demand and supply adjustments really kick in. I do have history as an imperfect guide. In 1972 and later in 1978 we had some serious price shocks in oil:

Depending on if you date the last run-up in prices from '72 or '78, it took 5-10 years for supply and demand to sort themselves out (including the change in some structural factors, like US pricing regulations) before prices started falling. We are currently about 6 years into the current oil price run-up, so I think it is reasonable to expect a correction in the next 2-3 years of fairly substantial magnitude.

Postscript: I have left out any discussion of the dollar, which has to play into this strongly, because what I understand about monetary policy and currencies wouldn't fill a thimble. Suffice it to say that a fall in value of the dollar will certainly raise the price, to the US, of oil, but at the same time rising prices of imported oil tends to make the dollar weaker. I don't know enough to sort out the chicken from the egg here,