Long time readers will know that if I were asked to relive my life doing something entirely different, I would like to try studying economic history. Today, in a bit of a coincidence, my son called me with a question about the effect of the Black Death in Europe on labor and grain prices ... just days after I had been learning about the exact same part of history in Professor Daileader's awesome Teaching Company course on the Middle Ages (actually he has three courses - early, high, late - which are all excellent).

From the beginning of the 14th century, Europe suffered a series of demographic disasters. Climate change in the form of the end of the Medieval warm period led to failed crops and several years of famine early in the century. Then, later in the century, the Black Death came... over and over, perhaps made worse by the fact that Europeans were weakened already from famine. As a result, the population of Europe dropped by something like half.

It is not entirely obvious to me what such a demographic disaster would do to prices. Panic and uncertainty usually drive them up in the near term, but what about after that? Both the supply and demand curves for most everything will be dropping in tandem. So what happens to prices?

In the case of the 14th century, we know the answer: the price of labor rose dramatically, while the price of grain dropped. The combination tended to bankrupt the landholding aristocracy, who went so far as to try to reimpose serfdom to get their finances back in balance (some things never change). The nobility pretty much failed at this in the West (England, France) and were met with a series of peasant revolts. They generally succeeded in the East (Germany, Poland, Russia) which is why a quasi-feudal agricultural system persisted so long in those countries.

But why? Why did grain price go down rather than up? Why did labor go in the opposite direction? I could look it up, but that is no fun.

A first answer, which does not satisfy

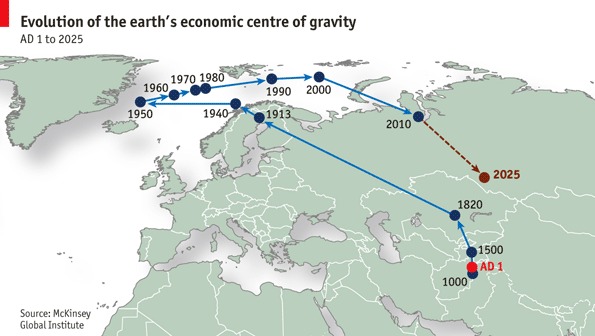

People who think of all of the middle ages as "the dark ages" miss the boom that occurred between 1000-1300. Population increased, and technology advanced (just because this technology seems pedestrian to us, like the plow harness for horses or the stirrup, does not make it any less so). It was the only time between about 300 and 1500 when the population was growing (a fact we climate skeptics will note coincided with the Medieval warm period).

But even without the setbacks of the 1300's, historians probably would argue that Europe was headed for a Malthusian collapse no matter what in the 14th century. An enormous amount of forest had been cleared and new farmland created, such that by 1300 some pretty marginal land was being farmed just so Europe could barely keep up with demand. At the margin, really low productivity land was being farmed.

So if there is a sudden 50% population cut, then that means that all that marginal farm land will be abandoned first. While the number of farmers would be cut in half, production would be reduced by less than half because presumably the least productive farms would be abandoned first. With demand cut by half and production cut by less than half, prices would fall for grain.

But this doesn't work for labor. The same argument should apply. To get everyone fed, we would actually need less than half the prior labor force because they would concentrate on the best land. Labor prices should fall in this model as well, but in fact they went up. A lot. In fact, they went up not by a few percent but by multiples, enough to cause enormous social problems across Europe.

A second answer, that makes more sense

After thinking about this for a while, I came to realize that I had the wrong model for the economy in my head. I was thinking about our modern economy. If suddenly, say, online retailing reduces demand for physical stores dramatically, people close stores and redeploy capital and labor and assets to other investments in other industries. That is how I was thinking about the Middle Ages.

But it may be more correct to see the Middle Ages as a one product economy. There was agriculture, period. Everything else was a rounding error.

So now let's think about the "farmers" in the Middle Ages. They are primarily all the 1%, the titled nobility, who either farm big estates with peasant labor or lease large parts of their estates to peasants for farming.

OK, half the population is suddenly gone. The Noble's family has lots of death but someone is still around to inherit. They have a big estate where growing grain supports their lifestyle as well as any military obligations they may have to their lord (though this style of fighting with knights on horseback supported by grants of land is having its last hurrah in the 100 years war).

Then grain prices collapse. That is a clear pricing signal. In the modern economy, that would tell us to get out and find a new place for our capital. So, as Lord Coyote of the Castle Aaaaargh, I am going to do what, exactly? How can I redeploy my capital, when it is essentially illiquid? I can't sell the family land. And if I did, land prices, along with grain prices and the demographic collapse, are falling through the floor. And even if I could sell for cash, what would I do for a living? What would I reinvest the money in? Running an estate is all I know. It's all anyone knows. I have to support myself and my 3 mistresses and my squires and my string of warhorses.

All I can do is try to farm the land I have always farmed. And everyone else does the same. The result is far more grain than anyone needs with the reduced population, so prices fall. But I still need the same number of people to grow the food, irregardless of the price it fetches, but there are now half as many workers available so the price of labor goes through the roof. When grain demand collapsed, there was no way to clear the excess capacity. It turns out everyone had a nearly vertical supply curve, because irregardless of price, they had nothing else they could do with their time and money. You can see now why they tried to solve their problem by reimposing serfdom (combined with price controls, a bad idea for Diocletian and for Nixon and everyone in between).

Of course, nothing is stuck forever. One way capacity cleared was through the growth of the bureaucratic state over the next 2 centuries. Nobles eventually had to find some new way to support themselves, and did so by taking jobs in growing state bureaucracies. They became salaried ministers rather than feudal knights supported by agriculture. At the same time, rising wealth among the 99% non-nobility allowed kings to support themselves through taxes rather than the granting of fiefs, which in turn paid for the nobility to take jobs in the bureaucracy and paid for peasant armies with guns and bows that replaced the lords fighting on horseback. So in the long term, the price signal was inordinately powerful -- so powerful it helped reshape much of European government and society.

By the way, if you are reading this expecting some point about modern politics, sorry. Just something I was thinking about and it helped to write it down. Comments are appreciated. I still have not cribbed the answer from the history texts yet.