Adverse Selection

From Radley Balko, this is just staggering:

Federal employees’ job security is so great that workers in many agencies are more likely to die of natural causes than get laid off or fired, a USA TODAY analysis finds.

Death — rather than poor performance, misconduct or layoffs — is the primary threat to job security at the Environmental Protection Agency, the Small Business Administration, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Office of Management and Budget and a dozen other federal operations.

The federal government fired 0.55% of its workers in the budget year that ended Sept. 30 — 11,668 employees in its 2.1 million workforce. Research shows that the private sector fires about 3% of workers annually for poor performance . . .

The 1,800-employee Federal Communications Commission and the 1,200-employee Federal Trade Commission didn’t lay off or fire a single employee last year. The SBA had no layoffs, six firings and 17 deaths in its 4,000-employee workforce.

When job security is at a premium, the federal government remains the place to work for those who want to avoid losing a job. The job security rate for all federal workers was 99.43% last year and nearly 100% for those on the job more than a few years . . .

White-collar federal workers have almost total job security after a few years on the job. Last year, the government fired none of its 3,000 meteorologists, 2,500 health insurance administrators, 1,000 optometrists, 800 historians or 500 industrial property managers.

The nearly half-million federal employees earning $100,000 or more enjoyed a 99.82% job security rate in 2010. Only 27 of 35,000 federal attorneys were fired last year. None was laid off.

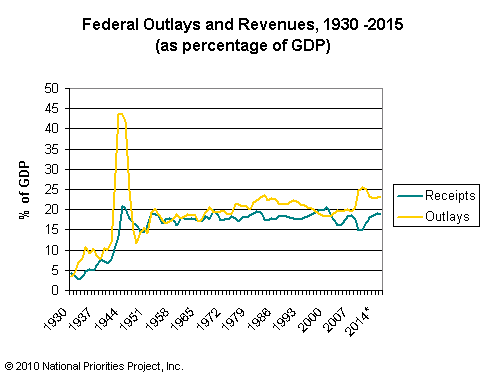

Forgetting for a minute the adverse selection and incentive problems from preferentially attracting folks who want to work in an environment without any accountability for performance, how can an institution that is running $1 trillion over budget not have any layoff either?

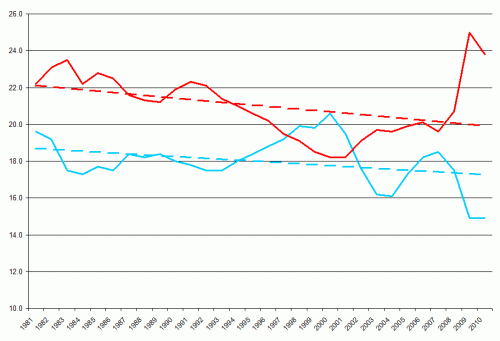

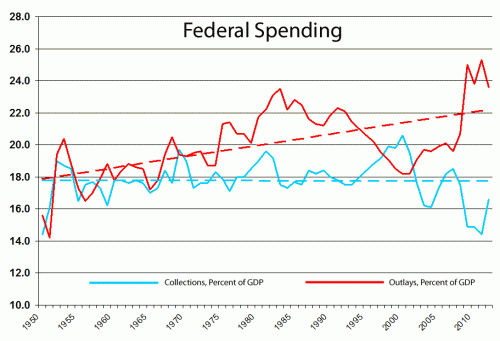

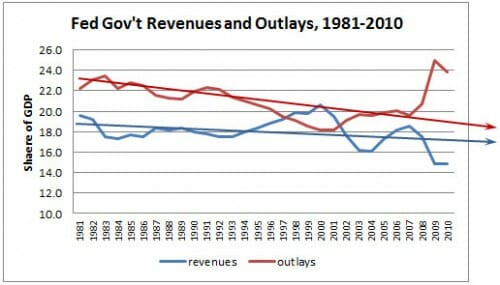

Update: Here is the data

Update: Here is the data