Trend That is Not A Trend: Rolling Stone Wildfire Article

Rolling Stone brings us an absolutely great example of an article that claims a trend without actually showing the trend data, and where the actual data point to a trend in the opposite direction as the one claimed.

I won't go into the conclusions of the article. Suffice it to say it is as polemical as anything I have read of late and could be subtitled "the Tea Party and Republicans suck." Apparently Republicans are wrong to criticize government wildfire management and do so only because they suck, and the government should not spend any effort to fight wildfires that threaten private property but does so only because Republicans, who suck, make them. Or something.

What I want to delve into is the claim by the author that wildfires are increasing due to global warming, and only evil Republicans (who suck) could possibly deny this obvious trend (numbers in parenthesis added so I can reference passages below):

But the United States is facing an even more basic question: How should we manage fire, given the fact that, thanks to climate change, the destruction potential for wildfires across the nation has never been greater? In the past decade alone, at least 10 states – from Alaska to Florida – have been hit by the largest or most destructive wildfires in their respective histories (1). Nationally, the cost of fighting fires has increased from $1.1 billion in 1994 to $2.7 billion in 2011.(2)

The line separating "fire season" from the rest of the year is becoming blurry. A wildfire that began in Colorado in early October continued smoldering into May of this year. Arizona's first wildfire of 2013 began in February, months ahead of the traditional firefighting season(3). A year-round fire season may be the new normal. The danger is particularly acute in the Intermountain West, but with drought and record-high temperatures in the Northwest, Midwest, South and Southeast over the past several years, the threat is spreading to the point that few regions can be considered safe....

For wildland firefighters, the debate about global warming was over years ago. "On the fire lines, it is clear," fire geographer Michael Medler told a House committee in 2007. "Global warming is changing fire behavior, creating longer fire seasons and causing more frequent, large-scale, high-severity wildfires."...(4)

Scientists have cited climate change as a major contributor in some of the biggest wildfires in recent years, including the massive Siberian fires during a record heat wave in 2010 and the bushfires that killed 173 people in Australia in 2009.(5)...

The problem is especially acute in Arizona, where average annual temperatures have risen nearly three-quarters of a degree Fahrenheit each decade since 1970, making it the fastest-warming state in the nation. Over the same period, the average annual number of Arizona wildfires on more than 1,000 acres has nearly quadrupled, a record unsurpassed by any other state and matched only by Idaho. One-quarter of Arizona's signature ponderosa pine and mixed-conifer forests have burned in just the past decade. (6)...

At a Senate hearing in June, United States Forest Service Chief Thomas Tidwell testified that the average wildfire today burns twice as many acres as it did 40 years ago(7). "In 2012, over 9.3 million acres burned in the United States," he said – an area larger than New Jersey, Connecticut and Delaware combined. Tidwell warned that the outlook for this year's fire season was particularly grave, with nearly 400 million acres – more than double the size of Texas – at a moderate-to-high risk of burning.(8)

These are the 8 statements I can find to support an upward trend in fires. And you will note, I hope, that none of them include the most obvious data - what has the actual trend been in number of US wildfires and acres burned. Each of these is either a statement of opinion or a data point related to fire severity in a particular year, but none actually address the point at hand: are we getting more and larger fires?

Maybe the data does not exist. But in fact it does, and I will say there is absolutely no way, no way, the author has not seen the data. The reason it is not in this article is because it does not fit the "reporters" point of view so it is left out. Here is where the US government tracks fires by year, at the National Interagency Fire Center. To save you clicking through, here is the data as of this moment:

Well what do you know? The number of fires and the acres burned in 2013 are not some sort of record high -- in fact they actually are the, respectively, lowest and second lowest numbers of the last 10 years. In fact, both the number of fires and the total acres burned are running a third below average.

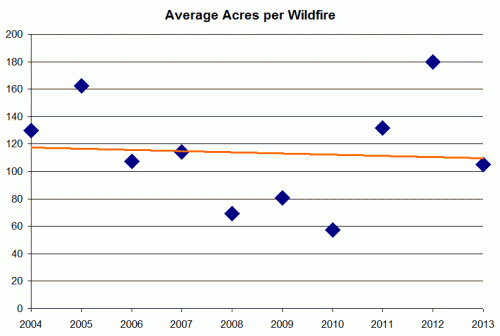

The one thing this does not address is the size of fires. The author implies that there are more fires burning more acres, which we see is clearly wrong, but perhaps the fires are getting larger? Well, 2012 was indeed an outlier year in that fires were larger than average, but 2013 has returned to the trend which has actually been flat to down, again exactly opposite of the author's contention (data below is just math from chart above)

In the rest of the post, I will briefly walk through his 8 statements highlighted above and show why they exhibit many of the classic fallacies in trying to assert a trend where none exists. In the postscript, I will address one other inconsistency from the article as to the cause of these fires which is a pretty hilarious of how to turn any data to supporting you hypothesis, even if it is unrelated. Now to his 8 statements:

(1) Again, no trend here, this is simply a single data point. He says that 10 states have set in one year or another in the last decade a record for one of two variables related to fires. With 50 states and 2 variables, we have 100 measurements that can potentially hit a record in any one year. So if we have measured fires and fire damage for about 100 years (about the age of the US Forest Service), then we would expect on average 10 new records every decade, exactly what the author found. Further, at least one of these -- costliness of the fires -- should be increasing over time due to higher property valuations and inflation, factors I am betting the author did not adjust for.

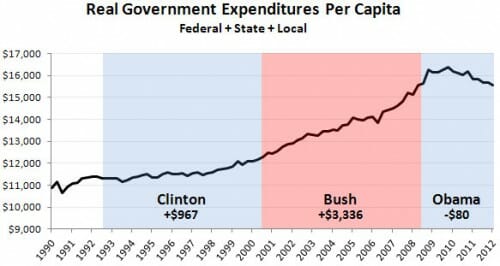

(2) This cost increase over 17 years represents a 5.4% per year inflation. It is very possible this is entirely due to changes in firefighting unit costs and methods rather than any change in underlying fire counts.

(3) This is idiotic, a desperate reach by an author with an axe to grind. Wildfires in Arizona often occur out of fire season. Having a single fire in the winter means nothing.

(4) Again, we know the data does not support the point. If the data does not support your point, find some "authority" that will say it is true. There is always someone somewhere who will say anything is true.

(5) It is true that there are scientists who have blamed global warming for these fires. Left unmentioned is that there are also scientists who think that it is impossible to parse the effect of a 0.5C increase in global temperatures from all the other potential causes of individual weather events and disasters. If there is no data to support a trend in the mean, it is absolutely irresponsible to claim causality in isolated data points in the tails of the distribution

(6) The idea that temperatures in Arizona have risen 3/4 a degree F for four decades is madness. Not even close. This would be 3F, and there is simply no basis in any reputable data base I have seen to support this. It is potentially possible to take a few AZ urban thermometers to see temperature increases of this magnitude, but they would be measuring mostly urban heat island effects, and not rural temperatures that drive wildfires (more discussion here). The statement that "the average annual number of Arizona wildfires on more than 1,000 acres has nearly quadrupled" is so awkwardly worded we have to suspect the author is reaching here. In fact, since wildfires average about 100 acres, the 1000 acre fire is going to be rare. My bet is that this is a volatility in small numbers (e.g. 1 to 4) rather than a real trend. His final statement that "One-quarter of Arizona's signature ponderosa pine and mixed-conifer forests have burned in just the past decade" is extremely disingenuous. The reader will be forgiven for thinking that a quarter of the trees in Arizona have burned. But in fact this only means there have been fires in a quarter of the forests -- a single tree in one forest burning would likely count for this metric as a forest which burned.

(7) This may well be true, but means nothing really. It is more likely, particularly given the evidence of the rest of the article, to be due to forest management processes than global warming.

(8) This is a data point, not a trend. Is this a lot or a little? And remember, no matter how much he says is at risk (and remember this man is testifying to get more budget money out of Congress, so he is going to exaggerate) the actual acreage burning is flat to down.

Postscript: The article contains one of the most blatant data bait and switches I have ever seen. The following quote is taken as-is in the article and has no breaks or editing and nothing left out. Here is what you are going to see. All the way up to the last paragraph, the author tells a compelling story that the fires are due to a series of USFS firefighting and fuel-management policies. Fair enough. His last paragraph says that Republicans are the big problem for opposing... opposing what? Changes to the USFS fire management practices? No, for opposing the Obama climate change plan. What?? He just spent paragraphs building a case that this is a fire and fuel management issue, but suddenly Republicans suck for opposing the climate change bill?

Like most land in the West, Yarnell is part of an ecosystem that evolved with fire. "The area has become unhealthy and unnatural," Hawes says, "because fires have been suppressed." Yarnell is in chaparral, a mix of small juniper, oak and manzanita trees, brush and grasses. For centuries, fires swept across the chaparral periodically, clearing out and resetting the "fuel load." But beginning in the early 1900s, U.S. wildfire policy was dominated by fire suppression, formalized in 1936 as "the 10 a.m. rule" – fires were to be extinguished by the morning after they were spotted; no exceptions. Back in the day, the logic behind the rule appeared sound: If you stop a fire when it's small, it won't become big. But wildland ecosystems need fire as much as they need rain, and it had been some 45 years since a large fire burned around Yarnell. Hawes estimates that there could have been up to five times more fuel to feed the Yarnell Hill fire than was natural.

The speed and intensity of a fire in overgrown chaparral is a wildland firefighter's nightmare, according to Rick Heron, part of another Arizona crew that worked on the Yarnell Hill fire. Volatile resins and waxy leaves make manzanita "gasoline in plant form," says Heron. He's worked chaparral fires where five-foot-tall manzanitas produced 25-foot-high flames. Then there are the decades of dried-up grasses, easily ignitable, and the quick-burning material known as "fine" or "flash" fuels. "That's the stuff that gets you," says Heron. "The fine, flashy fuels are just insane. It doesn't look like it's going to be a problem. But when the fire turns on you, man, you can't outdrive it. Let alone outrun it."

Beginning with the Forest Service in 1978, the 10 a.m. rule was gradually replaced by a plan that gave federal agencies the discretion to allow fires to burn where appropriate. But putting fire back in the landscape has proved harder to do in practice, where political pressures often trump science and best-management practices. That was the case last year when the Forest Service once again made fire suppression its default position. Fire managers were ordered to wage an "aggressive initial attack" on fires, and had to seek permission to deviate from this practice. The change was made for financial reasons. Faced with skyrocketing costs of battling major blazes and simultaneous cuts to the Forest Service firefighting budget, earlier suppression would, it was hoped, keep wildfires small and thus reduce the cost of battling big fires.

Some critics think election-year politics may have played a role in the decision. "The political liability of a house burning down is greater than the political liability of having a firefighter die," says Kierán Suckling, head of the Tucson-based Center for Biological Diversity. "If they die, you just hope that the public narrative is that they were American heroes."

The problem will only get worse as extremist Republicans and conservative Democrats foster a climate of malign neglect. Even before President Obama unveiled a new climate-change initiative days before the fire, House Speaker John Boehner dismissed the reported proposal as "absolutely crazy." Before he was elected to the Senate last November, Jeff Flake, then an Arizona congressman, fought to prohibit the National Science Foundation from funding research on developing a new model for international climate-change analysis, part of a program he called "meritless." The biggest contributor to Flake's Senate campaign was the Club for Growth, whose founder, Stephen Moore, called global warming "the biggest myth of the last one hundred years."

By the way, the Yarnell firefighters did not die due to global warming or even the 10am rule. They died due to stupidity. Whether their own or their leaders may never be clear, but I have yet to meet a single firefighter that thought they had any business being where they were and as out of communication as they were.