This is a reprise of a much older post, but it struck me as fairly timely.

I had a conversation the other day with a person I can best describe as a well-meaning technocrat. Though I am not sure he would put it this baldly, he tends to support a government by smart people imposing superior solutions on the sub-optimizing masses. He was lamenting that allowing a company like GM to die is dumb, and that a little bit of intelligent management would save all those GM jobs and assets. Though we did not discuss specifics, I presume in his model the government would have some role in this new intelligent design (I guess like it had in Amtrak?)

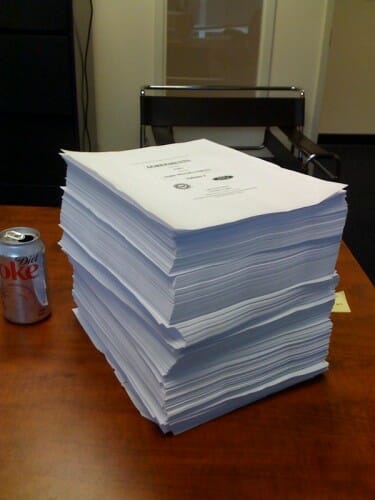

There are lots of sophisticated academic models for the corporation. I have even studied a few. Here is my simple one:

A corporation has physical plant (like factories) and workers of various skill levels who have productive potential. These physical and human assets are overlaid with what we generally shortcut as "management" but which includes not just the actual humans currently managing the company but the organization approach, the culture, the management processes, its systems, the traditions, its contracts, its unions, the intellectual property, etc. etc. In fact, by calling all this summed together "management", we falsely create the impression that it can easily be changed out, by firing the overpaid bums and getting new smarter guys. This is not the case - Just ask Ross Perot. You could fire the top 20 guys at GM and replace them all with the consensus all-brilliant team and I still am not sure they could fix it.

All these management factors, from the managers themselves to process to history to culture could better be called the corporate DNA*. And DNA is very hard to change. Walmart may be freaking brilliant at what they do, but demand that they change tomorrow to an upscale retailer marketing fashion products to teenage girls, and I don't think they would ever get there. Its just too much change in the DNA. Yeah, you could hire some ex Merry-go-round** executives, but you still have a culture aimed at big box low prices, a logistics system and infrastructure aimed at doing same, absolutely no history or knowledge of fashion, etc. etc. I would bet you any amount of money I could get to the GAP faster starting from scratch than starting from Walmart. For example, many folks (like me) greatly prefer Target over Walmart because Target is a slightly nicer, more relaxing place to shop. And even this small difference may ultimately confound Walmart. Even this very incremental need to add some aesthetics to their experience may overtax their DNA.

Corporate DNA acts as a value multiplier. The best corporate DNA has a multiplier greater than one, meaning that it increases the value of the people and physical assets in the corporation. When I was at a company called Emerson Electric (an industrial conglomerate, not the consumer electronics guys) they were famous in the business world for having a corporate DNA that added value to certain types of industrial companies through cost reduction and intelligent investment. Emerson's management, though, was always aware of the limits of their DNA, and paid careful attention to where their DNA would have a multiplier effect and where it would not. Every company that has ever grown rapidly has had a DNA that provided a multiplier greater than one... for a while.

But things change. Sometimes that change is slow, like a creeping climate change, or sometimes it is rapid, like the dinosaur-killing comet. DNA that was robust no longer matches what the market needs, or some other entity with better DNA comes along and out-competes you. When this happens, when a corporation becomes senescent, when its DNA is out of date, then its multiplier slips below one. The corporation is killing the value of its assets. Smart people are made stupid by a bad organization and systems and culture. In the case of GM, hordes of brilliant engineers teamed with highly-skilled production workers and modern robotic manufacturing plants are turning out cars no one wants, at prices no one wants to pay.

Changing your DNA is tough. It is sometimes possible, with the right managers and a crisis mentality, to evolve DNA over a period of 20-30 years. One could argue that GE did this, avoiding becoming an old-industry dinosaur. GM has had a 30 year window (dating from the mid-seventies oil price rise and influx of imported cars) to make a change, and it has not been enough. GM's DNA was programmed to make big, ugly (IMO) cars, and that is what it has continued to do. If its leaders were not able or willing to change its DNA over the last 30 years, no one, no matter how brilliant, is going to do it in the next 2-3.

So what if GM dies? Letting the GM's of the world die is one of the best possible things we can do for our economy and the wealth of our nation. Assuming GM's DNA has a less than one multiplier, then releasing GM's assets from GM's control actually increases value. Talented engineers, after some admittedly painful personal dislocation, find jobs designing things people want and value. Their output has more value, which in the long run helps everyone, including themselves.

The alternative to not letting GM die is, well, Europe (and Japan). A LOT of Europe's productive assets are locked up in a few very large corporations with close ties to the state which are not allowed to fail, which are subsidized, protected from competition, etc. In conjunction with European laws that limit labor mobility, protecting corporate dinosaurs has locked all of Europe's most productive human and physical assets into organizations with DNA multipliers less than one.

I don't know if GM will fail (but a lot of other people have opinions) but if it does, I am confident that the end result will be positive for America.

* Those who accuse me of being more influenced by Neal Stephenson's Snow Crash than Harvard Business School may be correct.

** Gratuitous reference aimed at forty-somethings who used to hang out at the mall. In my town, Merry-go-round was the place teenage girls went if they wanted to dress like, uh, teenage girls. I am pretty sure the store went bust a while back.