Storm Frequency

I already discussed Newsweek's happy little ad hominem attack on climate skeptics here. However, as promised, I wanted to talk about the actual, you know, science for a bit, starting from the Newsweek author's throwaway statement that she felt required no

proof, "The frequency of Atlantic hurricanes has already doubled in the

last century."

This is really a very interesting topic, much more interesting than following $10,000 of skeptics' money around in a global warming industry spending billions on research. One would think the answer to this hurricane question is simple. Can we just look up the numbers? Well, let's start there. Total number of Atlantic hurricanes form the HURDAT data base, first and last half of the last century:

1905-1955 = 366

1956-2006 = 458

First, you can see nothing like a doubling. This is an increase of 25%. So already, we see that in an effort to discredit skeptics for fooling America about the facts, Newsweek threw out a whopper that absolutely no one in climate science, warming skeptic or true believer, would agree with.

But let's go further, because there is much more to the story. Because 25% is a lot, and could be damning in and of itself. But there are problems with this data. If you think about storm tracking technology in 1905 vs. 2005, you might see the problem. To make it really clear, I want to talk about tornadoes for a moment.

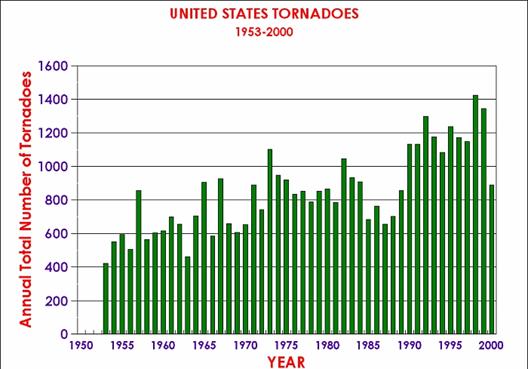

In An Inconvenient Truth, Al Gore and company said that global warming was increasing the number of tornadoes in the US. He claimed 2004 was the highest year ever for tornadoes in the US. In his PowerPoint slide deck (on which the movie was based) he sometimes uses this chart (form the NOAA):

Whoa, that's scary. Any moron can see there is a trend there. Its like a silver bullet against skeptics or something. But wait. Hasn't tornado detection technology changed over the last 50 years? Today, we have doppler radar, so we can detect even smaller size 1 tornadoes, even if no one on the ground actually spots them (which happens fairly often). But how did they measure smaller tornadoes in 1955 if no one spotted them? Answer: They didn't. In effect, this graph is measuring apples and oranges. It is measuring all the tornadoes we spotted by human eye in 1955 with all the tornadoes we spotted with doppler radar in 2000. The NOAA tries to make this problem clear on their web site.

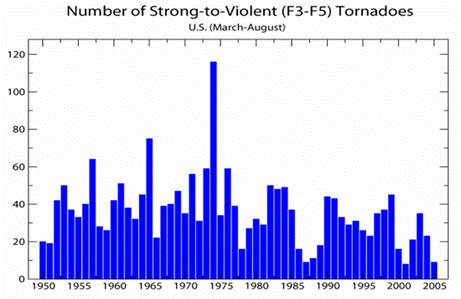

With increased national doppler

radar coverage, increasing population, and greater attention to tornado

reporting, there has been an increase in the number of tornado reports over the

past several decades. This can create a misleading appearance of an increasing

trend in tornado frequency. To better understand the true variability and trend

in tornado frequency in the US, the total number of strong to violent tornadoes

(F3 to F5 category on the Fujita scale) can be analyzed. These are the

tornadoes that would have likely been reported even during the decades before

Dopplar radar use became widespread and practices resulted in increasing

tornado reports. The bar chart below indicates there has been little trend in

the strongest tornadoes over the past 55 years.

So itt turns out there is a decent way to correct for this. We don't think that folks in 1955 were missing many of the larger class 3-5 tornadoes, so comparing 1955 and 2000 data for these larger tornadoes should be more apples to apples (via NOAA).

Well, that certainly is different (note 2004 in particular, given the movie claim). No upward trend at all when you get the data right. I wonder if Al Gore knows this? I am sure he is anxious to set the record straight.

OK, back to hurricanes. Generally, whether in 1905 or 2005, we know if a hurricane hits land in the US. However, what about all the hurricanes that don't hit land or hit land in some undeveloped area? Might it be that we can detect these better in 2006 with satellites than we could in 1905? Just like the tornadoes?

Well, one metric we have is US landfall. Here is that graph (data form the National Weather Service -- I have just extrapolated the current decade based on the first several years).

Not much of a trend there, though the current decade is high, in part due to the fact that it does not incorporate the light 2006 season nor the light-so-far 2007 season. The second half of the 20th century is actually lower than the first half, and certainly not "twice as large". But again, this is only a proxy. There may be reasons more storms are formed but don't make landfall (though I would argue most Americans only care about the latter).

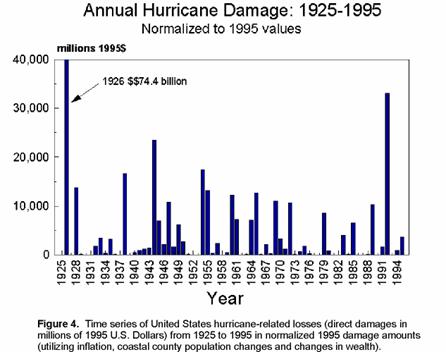

But what about hurricane damages? Everyone knows that the dollar damages from hurricanes is way up. Well, yes. But the amount of valuable real estate on the United State's coast is also way up. Roger Pielke and Chris Landsea (you gotta love a guy studying hurricane strikes named Landsea) took a shot at correcting hurricane damages for inflation and the increased real estate value on the coasts. This is what they got:

Anyway, back to our very first data, several scientists are trying to correct the data for missing storms, particularly in earlier periods. There is an active debate here about corrections I won't get into, but suffice it to say the difference between the first half of the 20th century to the latter half in terms of Atlantic hurricane formations is probably either none or perhaps a percentage increase in the single digits (but nowhere near 100% increase as reported by Newsweek).

Debate continues, because there was a spike in hurricanes from 1995-2005 over the previous 20 years. Is this anomalous, or is it similar to the spike that occurred in the thirties and forties? No one is sure, but isn't this a lot more interesting than figuring out how the least funded side of a debate gets their money? And by the way, congratulations again to MSM fact-checkers.

My layman's guide to skepticism of catastrophic man-made global warming is here. A shorter, 60-second version of the best climate skeptic's arguments is here.

Update: If the author bothered to have a source for her statement, it would probably be Holland and Webster, a recent study that pretty much everyone disagrees with and many think was sloppy. And even they didn't say activity had doubled. Note the only way to get a doubling is to cherry-pick a low decade in the first half of the century and a high decade in the last half of the century and compare just those two decades -- you can see this in third paragraph of the Scientific American article. This study bears all the hallmarks -- cherry picking data, ignoring scientific consensus, massaging results to fit an agenda -- that the Newsweek authors were accusing skeptics of.

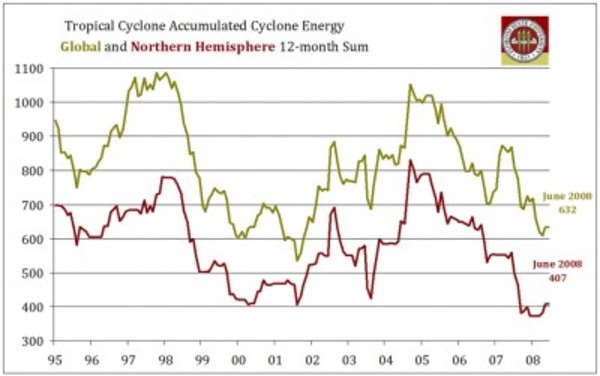

Update #2: The best metric for hurricane activity is not strikes or numbers but accumulated cyclonic energy. Here is the ACE trend, as measured by Florida State. As you can see, no upward trend.