Update: Just one day after this story, the Lancet published a study showing that B.1.1.7 not likely more deadly than other variants. As predicted below.

The New York Times has scary red maps of Europe on its front page today (at least in the version we get in AZ) implying mass death from new COVID variants. Given the prominence of COVID in the news and our lives, there is certainly a story here. But as usual with American media coverage of COVID, there is absolutely no balance here. The article highlights new developments in the virus, which is helpful, but does so in a largely data-free manager and simultaneously engages in the crudest of rhetorical tricks to make the situation seem far worse than it is. Here are a few pointers to how to read through this mess.

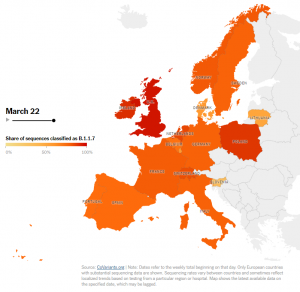

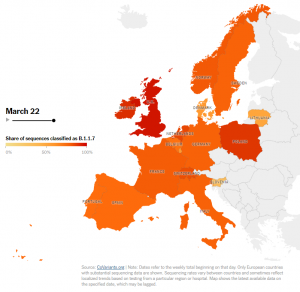

- The use of color on the front page maps is not accidental. When the media wants you to be scared, it uses red on maps and scales it so that even small changes in variables result in a map going from green or white or blue to solid red and orange. No exception here. When one glances at the front page, one likely assumes that this is a map of spread of death or new case counts, but in fact it is merely a map of one new variant as a percentage of other new variants. It says nothing about death or case counts.

- The article attempts to use certain rhetorical framings to imply that increases in cases and/or deaths are due to this new variant. For example:

The variant is now spreading in at least 114 countries. Nowhere, though, are its devastating effects as visible as in Europe, where thousands are dying each day and countries’ already-battered economies are once again being hit by new restrictions on daily life.

and this even more egregious example:

What happened this winter in the U.K. was mass death and deluged hospitals on a scale not seen earlier in the pandemic. Since B.1.1.7 was first sampled in late September, 85,000 people have died. Four million people — one out of every 17 Britons — have recorded infections.

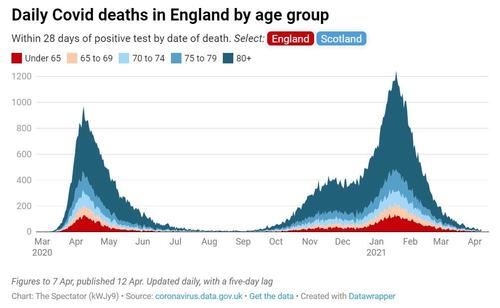

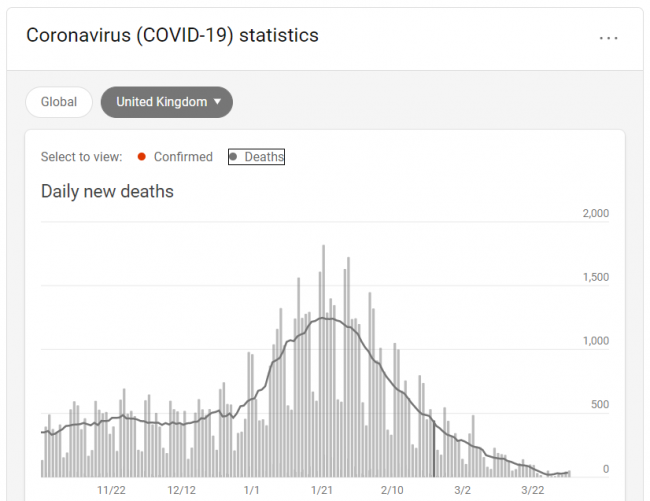

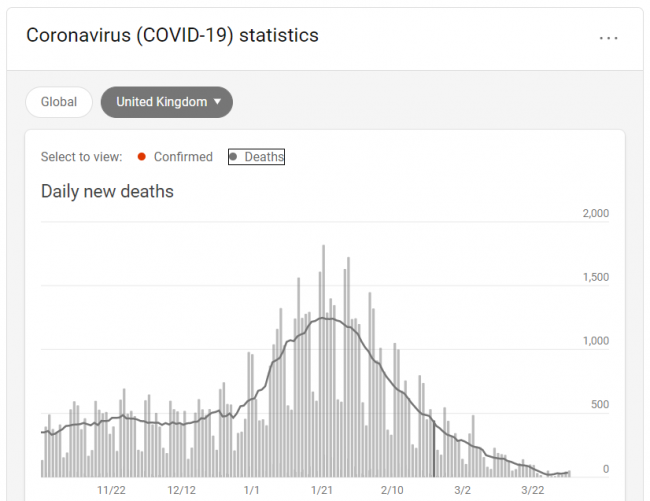

So 85,000 people died from this variant? Well, they want you to think that -- but they were careful that while implying that (which would not at all be true) they do not actually say that. When you think about it - especially given that there are now dozens of COVID variants - this sentence means exactly nothing. It's like saying that since Biden took office, thousands of people have died of cancer. Here is the UK deaths chart (from Google, not in the NY Times article):

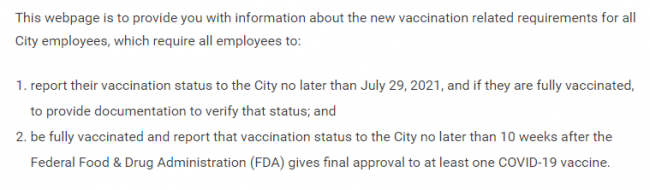

You would certainly never know from this article that deaths in the UK have basically gone to zero. This chart shows exactly the same seasonal pattern we are seeing everywhere, including in places like Arizona where we have had few if any of this new variant. This picture has become the great totalitarian Rorschach test of the 21st century, with everyone reading their own preferred causes into these seasonal humps (opened too soon! variants! spring break! evil Republican governor!)

By the way, I will save you clicking through the Times link above that says "mass death and delayed hospitals" in an attempt to see the data. There is none. Just like with the overloaded hospital meme in the US, the article is quotes from a few harried doctors and funeral home managers and zero data. The first "overloaded hospital" story I see with actual occupancy numbers compared to the same months in prior years will be the first. In this case there really is no excuse for this, as the NHS apparently keeps pretty detailed daily hospital records and puts them all online here. So I looked at the week including January 21, which looks like the peak of critical care at least in the death chart. On 1/21/21, there were apparently 3 acute and emergency care diverts in the whole of England, and it is not even clear if these were due to capacity issues. Other days that week were generally on 3 as well (I don't know how they count so I don't know if these are the same 3 people all week or different people each day). Occupancy of acute and emergency beds was around 87%. For comparison, the January 2019 report from the same site showed acute and critical care occupancy of 85%. The site cautions that with the segregation of COVID and non-COVID patients, capacity is harder to manage (a basic tenant one learns in any operations course) but it is hard to gauge by how much. But all this sort of discussion and outlining of facts that are so easy to find is missing from the article, as the whole point is to scare, not to inform. After all, reciting statistical facts about vampire incidents is not the best way to tell a scary ghost story around the camp fire.

- The article keeps saying that this variant is thought to be more transmissible and more deadly. Towards the very end they get the most specific when they say:

The variant is believed to be about 60 percent more contagious and 67 percent deadlier than the original version of the virus.

If you follow the link, you have to go through an Easter egg hunt of clicks, but eventually one gets to this metastudy looking at a number of results. I am not even going to pretend to have expertise in reading and interpreting these results, but I would observe that a) the claimed 67% number seems at the high end of a lot of the results; b) 67% is awfully precise for studies who summarize their study results as this variant "may" and "probably" be more deadly; and c) the sample sizes here are really small and pretty skewed (most seem to be dealing with people already hospitalized or at least showing symptoms). My personal bet is that we will see a story buried on page 34 in August saying that original relative death studies for this variant appear to have been exaggerated. When the NY Times is hyping a scare story that increases the power of government, particularly in a Democratic administration, take the under.

- My understanding is that most deadly viruses tend to mutate over time to be less rather than more deadly. More transmissive but less deadly is the ideal for a virus trying to spam copies of itself across the globe. I have yet to see any discussion in any article of this fact along with any hypothesis of why COVID might be behaving differently (since according to the media every damn variant is more scary than the last one). There may be a reason, and it would be an interesting discussion -- as well as an obvious on of interest to readers -- but I have yet to see it.

I really should not get that worked up about all this -- after all, my blog certainly is not even-handed. But my concern is

- The undercurrent of all these stories is essentially "so shut up and obey."

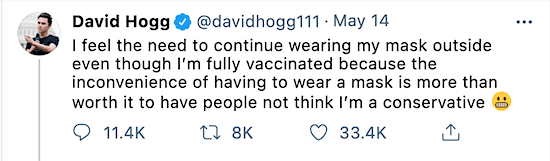

- No criticism or skepticism is being allowed by most of the major gatekeepers. I can say this kind of stuff because I have a small audience, but once one gets any sort of prominence, such skepticism no matter how well-grounded in facts will be memory-holed. Take this story. The claim that children don't need masks is perfectly justifiable for a disease that is deadly for octogenarians but milder than the flu for kids. We could have a discussion about this and people can disagree, but it is a totally reasonable topic for public discourse. To ban this can't be due to science, it can only be a quasi-totalitarian deference to authority -- President Biden says we need masks so no one should publicly disagree with him.

Be warned -- totalitarians have not missed the significance of this nor that the government seems to be getting away with it. You are going to see a spate of issues all reframed as public health issues -- guns, race, climate, immigration -- with folks claiming that newly established COVID-related dictatorial powers need to be applied to their pet issues as well,

I don't think in the history of this country the general populace** has been subjected to the sorts of limitations to individual freedoms that have been imposed over the last year, often by executive order without even involvement of the legislature. Sometimes by public health officials who are not even elected. Even in wartime I can't think of any affront to individual liberties that was as bad as the combination of lockdowns, school closures, and business closures. To have all that happen is bad enough. But to have the gatekeepers of the public discourse declare that not only are we going to do all these unprecedented authoritarian things, but we are not even going to allow public skepticism of them --that is really scary. Historically, all the worst ideas have been accompanied by bans on public criticism.

** Clearly minority populations have been subjected to worse. Enslavement of African-Americans, internment of Japanese-Americans, and near-genocidal actions taken against various native American groups come to mind.