How The Media Exaggerates to Scare You -- Often In Support of Growing the State

I find the WSJ to be more readable than most modern newspapers, but that does not mean it doesn't play exactly the same silly media games every other media outlet does.

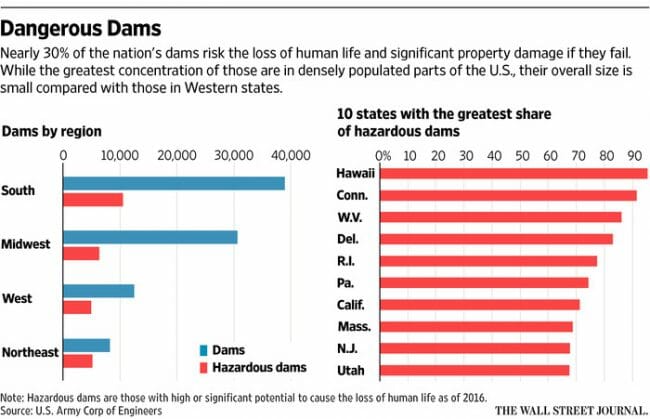

This article is about a legitimately dangerous dam in California that is being rebuilt to accommodate new learning about how earthen dams behave in seismic events. The authors attempt to extrapolate from this example to highlight a larger threat to the nation. They use this chart:

A reader who is not careful and does not read the fine print, which means probably most all of them, will assume that "dangerous" and "hazardous" as used in this chart refers to dams that are somehow deficient. But in fact, these terms in this chart refer only to the fact that IF a particular dam were to fail, people and property might be at risk. The data here say nothing about whether these dams are somehow deficient. Actually, if anything, I am surprised the number by this definition is as small as 30%.

The actual number of deficient dams that are dangerous to human life is actually an order of magnitude smaller than these numbers, as given in the text:

An estimated 27,380 or 30% of the 90,580 dams listed in the latest 2016 National Inventory of Dams are rated as posing a high or significant hazard. Of those, more than 2,170 are considered deficient and in need of upgrading, according to a report by the American Society of Civil Engineers. The inventory by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers doesn’t break out which ones are deficient.

So if we accept the ASCE numbers as valid (and I am always skeptical of their numbers, they tend to exaggerate in order to try to generate business for their profession) the actual numbers of dams that are really hazardous is no more than 2,170. That strikes me as a reasonably high number, and certainly a good enough reason to write a story, but the media simply cannot help themselves and insist on exaggerating every risk higher than it is.

It's kind of a in-between kind of thing. High-hazard dams that are not currently structurally deficient can still prove to be an imminent threat to life and property, given the right conditions. Incidents such as this spring's Lake Oroville Dam situation show that: It was fine, until it wasn't and that was right before a large rain event which caused a cascade of issues. And even then, it was managed. So there's some concern, but there's more frequently too much concern, and a lot of time and effort spent on analyzing and even fixing dams that really aren't a significant threat (and remember that a lot of these high hazard dams are actually roadways, with stormwater treatment on one side. It would take quite a lot for one of those to fail.

I actually wonder if 30% is a bit high for high hazard classifications, but where I work might be a little different from other places, for sure. I know that there's no way that 3 of 10 dams I've designed are high hazard.

New headline: "100% of dams could cause flooding if they fail"

not any different than Sea level rise of 3-8 ft by the end of the century if all the ice in greenland mel

I think journalists don't know the difference between "dangerous" and "hazardous" since those are technical terms and they can't be bothered anymore to be precise.

Not sure what the message is in the chart to the right. Delaware has about 83% hazardous dams? Delaware is flatter than Kansas. If a dam burst in Delaware, would anyone even know it?

IIRC, the Oroville dam was not "fine". Maintenance was neglected for a long time, and the emergency spillway was never constructed to stand up to being used in an emergency.