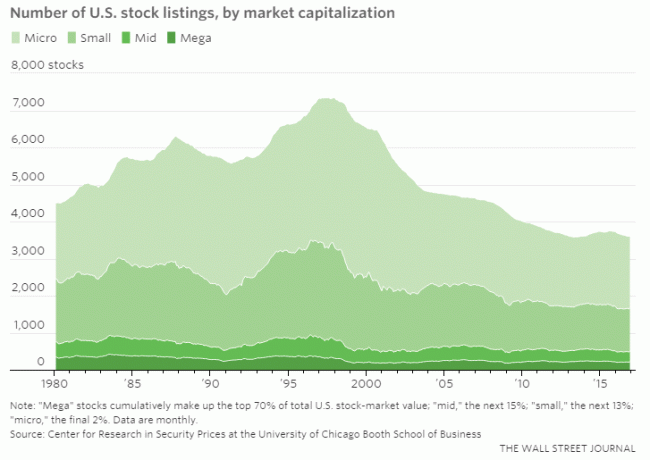

Where Have All The Public Companies Gone?

From the WSJ today, this interesting bit:

In less than two decades, more than half of all publicly traded companies have disappeared. There were 7,355 U.S. stocks in November 1997, according to the Center for Research in Security Prices at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business. Nowadays, there are fewer than 3,600....

“Twenty years ago, there were over 4,000 stocks smaller†than the inclusion cutoff for the Russell 2000, says Lubos Pastor, a finance professor at the University of Chicago. “That number is down to less than 1,000 today.â€

The article discusses the trend in the context of stock pickers having a smaller palette to work with, as it were, but obviously there are likely some economic implications here as well. The first words the popped into my head were "Dodd-Frank" but for all the problems with that law, the chart makes clear that most of the decline occurred long before that law was passed.

Postscript: The title of the article is "Stock Picking Is Dying Because There Are No More Stocks to Pick." Maybe, but I would have been less charitable by saying that it was because as a group stock pickers have never been able to out-perform the market averages, even when there were twice as many stocks to choose from.

Update: A reader writes:

Matt Levine, Bloomberg writer, has suggested recently that the reason this has happened is not that regulations on public companies have become especially onerous, it's that access to private money is easier now.

Public company regulations were always kind of onerous, but it was worth it to get access to the money only available in the public market. These days, when you can raise billions of dollars without ever going public, why bother?

In the context of stock-picking, I suppose all the good ones have moved to private equity firms. As I suppose, have gone the good industry analysts

Of course. The US is heading towards a European-style crony capitalist structure where relatively few large corporations work hand-in-glove with the government to balance the wants of the people against the efficiency and profitability of the companies. Which sounds all dreamy and perfect, but its "gains" are more than offset by cost of living increases due to the gross inefficiencies introduced, it eliminates the best innovators (small and medium-sized businesses), it severely restricts opportunities for self-employment, these companies get their assess kicked up and down the street by ones that operate with fewer fetters, and then you wind up with all sorts of protectionist and mercantilist nonsense that continues to make the poor poorer at the expense of the upper- and middle-classes. In other words, it's very progressive.

This is pure SOX. Tech crash started the decline, then knowing SOX would pass in 2002 and the cost of being public would increase drastically (almost 200% increase in accounting and financial infrastructure), chased a lot of small companies back into the private sphere in 2001/2002. I saw it happen a lot in the small biotech space.

+1. SOX increased the cost of being public, while at the same time better financialization decreased the advantage public companies have over private in access to capital.

Mean-regression? We're just a little below early 80's level of stock-listings. Picking 1997 as a reference point doesn't seem intellectually sound to draw conclusions from.

Yep. The tech company I worked for saw compliance costs of ~$1m/year which drove the company into acquisition by a larger company.

Bingo. The words that should pop into your head looking at this are "Sarbanes-Oxley". I work for a midsize tech company, nowadays worth a few billion dollars. The company was founded in the late 90's, was going to go public around the time of the crash, decided to hold off a bit, then SOX passed, and that was put *waaay* off. Eventually they did IPO in 2008. Last year they realized that was a big mistake, and went private again though a private equity firm.

I've worked in the tech industry for 20 years. Before SOX the game plan for startups was to develop a business, grow til there was a chance at an IPO, and use that to pay off initial capital, and develop a thriving company. After SOX, it was develop a likely business, then get bought out.

SOX for certain. The timing of the rapid decline starting in 2001. Also look at the composition - as you would expect with most regulations, the mega firms absorbed the additional cost while the smaller firms get squeezed out. Nearly all of the decline is in the small cap companies.

Does this mean that the argument in favour of private investors buying passive tracker funds ought to be modified by also encouraging them somehow to invest in private equity?

Correct.

I wonder if the decreased number of stocks is the big reason for the stock market surge. DJIA is based on a small number of stocks. If there are fewer stock, more money goes into the big ones.

When Sarbanes-Oxley was passed, many of us economists predicted a noteworthy decrease in public companies. The incentives to go private are huge in Sarbanes-Oxley. That would be an unintended consequence of that law - more companies escaping all public-company regulation rather than being subject to additional regulations.

I suspect a significant factor is private equity - i.e. the carried interest conversion of profits to capital gains for tax purposes. But perhaps the rise in private equity is a consequence. I know that I see a lot of companies in my sector (hospitality) owned by PE companies.

I'm thinking about big reason is that large investors have had trouble finding solid value in the market because since the late 90's tech boom it's been kind of schizophrenic. By using that easier private money, and timing the market, they can pick up a solid, profitable company cheap.

I have Dell firmly in mind as I write this, but I'm sure a few minutes research would find similar examples.