Risks of QE

So far, I have mainly been concerned about inflationary risks from quantitative easing, which is effectively a fancy term for substituting printed money for government debt (I know there are folks out there that swear up and down that QE does not involve printing (electronically of course) money, but it simply has to. Operation Twist, the more recent Fed action, is different, and does not involve printing money but essentially involves the Fed taking on longer-term debt in exchange for putting more shorter term debt on the market.

Scott Minder in the Financial Times highlights another potential problem:

In 2008, just before the first of two rounds of quantitative easing, the Federal Reserve had $41bn in capital and roughly $872bn in liabilities, resulting in a debt to equity ratio of roughly 21-to-one. The Federal Reserve’s portfolio had $480bn in Treasury securities with an asset duration of about 2.5 years. Therefore, a 100 basis point increase in interest rates would have caused the value of its portfolio to fall by 2.5 per cent, or $12bn. A loss of that magnitude would have been severe but not devastating.

By 2011, the Fed’s portfolio consisted of more than $2.6tn in Treasury and agency securities, mortgage bonds and other fixed income assets, and its debt-to-equity ratio had dramatically increased to 51-to-one. Under Operation Twist, the Fed swapped its short-term securities holdings for longer-term ones, thereby extending the duration of its portfolio to more than eight years. Now, a 100 basis point increase in interest rates would cause the market value of the Federal Reserve’s assets to fall by about 8 per cent, or $200bn, leaving it insolvent, with a capital deficit of about $150bn. Hypothetically, a 5 per cent rise in interest rates could cause a trillion dollar decline in the value of the Federal Reserve’s assets.

As the economy continues to expand, the Federal Reserve will eventually seek to normalise monetary policy, resulting in higher interest rates. In this scenario, the central bank could find that the market value of its portfolio has declined to the point where it no longer has enough sellable assets to adequately reduce the money supply and maintain the purchasing power of the dollar. Given US dependence on foreign capital flows, if the stability of the dollar is drawn into question, the ability of the US to finance its deficits may falter. The Federal Reserve could then find itself the buyer of last resort for Treasury securities. In doing so, the government would become hostage to its printing press, and a currency crisis or runaway inflation could take hold.

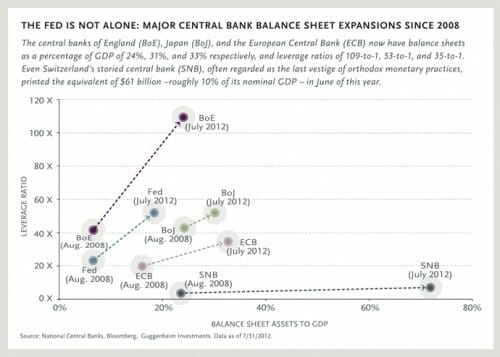

George Dorgan observes, on the pages of Zero Hedge, that European countries are taking even large balance sheet risks. The most surprising is the Swiss.

> it simply has to.

Indeed.

Given all of my other extreme opinions, it's somewhat surprising that I'm not 100% against the current currency regime (sovereign issued fiat currency, fractional reserve banking), because the idea of a gold standard seems even more chaotic and volatile.

Even if I am not a Keynesian, I do think that a decrease in the quantity of money is contractionary, and fractional reserve banking necessarily implies that deleveraging results in a decrease in the quantity of money...so when people pay down their debts (as they're doing now) then we ("we") need to either accept contraction or increase the money supply.

So, if we are to have fiat currency, and if we are to have a central bank, and if we intend to fight contraction, then we MUST take steps that increase the money supply.

...and that's what QE 1, 2, and 3 are about.

It's clear as day.

...so I find all the hand waving that "this is not printing money" to be utterly inane transparent lies.

Damn it, you need to print money, you are printing money, just admit it!

...but (and here my understanding grows thing), the point of QE over true running of the printing presses is that the knob that creates the excess dollars in the first place can be twisted back later to soak up the excess cash.

And this is a clever implementation detail.

That is the point of QE, the knob can be turned back. But, looking back over 40 years of gov't finances, you think the knob ever will be turned back?

The gov't could also reduce the universal service fee on your phone bill, now that 99.8% of US has access to wired/mobile phone service. Or it could spend more money than it has, providing dozens of cell phones to anyone who can show they are getting federal aid. Which will happen, I wonder?

Wasn't that just a really complicated way of saying that that the Fed can only reduce the money supply by the value of the securities and bonds it holds? What do liabilities have to do with anything?

}}}} which is effectively a fancy term for substituting printed money for government debt

Which is itself a fancy term for "inflating yourself out of debt", n'cest pas?

There is a second problem with increasing the interest rates back to historical norms. That problem is what it will do to Federal finances. If we have a $20 trillion debt, the a 5% interest rate means the Feds would need to pay $1 trillion in interest.

So those of us who planned to live off our savings are in deep trouble.