A Unified Theory of Poor Risk Management: What Climate Change Hysteria, the Anti-GMO Movement, and the Anti-Vaccination Movement Have in Common

After debating people online for years on issues from catastrophic man-made climate change to genetically-modified crops to common chemical hazards (e.g. BPA) to vaccination, I wanted to offer a couple quick thoughts on the common mistakes I see in evaluating risks.

1. Poor Understanding of Risk, and of Studies that Evaluate Risk

First, people are really bad at thinking about incremental risk above and beyond the background risk (e.g. not looking at "what is my risk of cancer" but "what is my incremental added risk from being exposed to X"). Frequently those incremental risks are tiny and hard to pick out of the background risk at any level of confidence. They also tend to be small compared to everyday risks on which people seldom focus. You have a far higher - almost two orders of magnitude - risk in the US of drowning in your own bathtub than you have in being subject to terrorism, but which do we obsess over?

Further, there are a lot of folks who seem all-to-ready to shoot off in a panic over any one scary study in the media. And the media loves this, because it drives the meter on their earnings, so they bend over backwards to look for studies with scary results and then make them sound even scarier. "Tater-tots Increase Risk of Ebola!" But in reality, most of these scary studies never get replicated and turn out to be mistaken. Why does this happen?

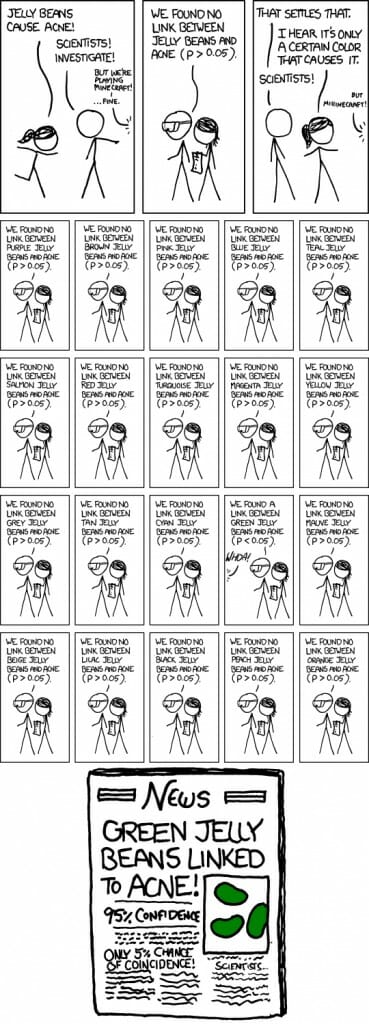

The problem is that every natural process is subject to random variation. Even without changing the conditions of an experiment, there is going to be random variation in measurements. For example, one population of white mice might have 6 cancers, but the next might have 12 and the next might have zero, all from natural variation. So the challenge of most experiments is to determine whether the thing one is testing (e.g. exposure to a particular substance) is actually changing the measurements in a population, or whether that change is simply the result of random variation. That is what the 95% confidence interval (that Naomi Oreskes wants to get rid of) really means. It means there is only a 5% chance that the results measured were due to natural variation.

This is a useful test, but I hope you can see how it can fail. Something like 5% of the time that one is measuring two things that actually are uncorrelated, the test is going to give you a false positive. Let's say in a year that the world does 1000 studies to test links that don't actually exist. Just from natural variation, 5% of these studies will still seem to show a link at the 95% confidence level. We will have 50 studies that year broadcasting false links. The media will proceed to scare the crap out of you over these 50 things.

I have never seen this explained better than in this XKCD cartoon (click to enlarge):

All of this is just exacerbated when there is fraud involved, an unfortunate but not unknown occurrence when reputations and large academic grants are on the line. This is why replication of the experiment is important. Do the study a second time, and all but 2-3 of these 50 "false positive" studies will fail to replicate the original results. Do it three times, and all will likely fail to replicate. This, for example, is exactly what happened with the vaccine-autism link -- it came out in one study with a really small population and some evidence of fraud, and was never replicated.

2. The Precautionary Principle vs. the Unseen, with a Dollop of Privilege Thrown In

When pressed to the wall too hard about the size and quality of the risk assessment, most folks subject to these panics will fall back on the "precautionary principle". I am not a big fan of the precautionary principle, so I will let Wikipedia define it so I don't create a straw man:

The precautionary principle or precautionary approach to risk management states that if an action or policy has a suspected risk of causing harm to the public or to the environment, in the absence of scientific consensus that the action or policy is not harmful, the burden of proof that it is not harmful falls on those taking an action.

I will observe that as written, this principle is inherently anti-progress. The proposition requires that folks who want to introduce new innovations must prove a negative, and it is very hard to prove a negative -- how do I prove there are no invisible aliens in my closet who may come out and eat me someday, and how can I possibly get a scientific consensus to this fact? As a result, by merely expressing that one "suspects" a risk (note there is no need listed for proof or justification of this suspicion), any advance may be stopped cold. Had we followed such a principle consistently, we would still all be subsistence farmers, vassals to our feudal lord.

One other quick note before I proceed, it turns out that proponents of the precautionary principle are very selective as to where they apply the principle. They feel like it absolutely must be applied to fossil fuel burning, or BPA use, or GMO's. But precautionary principle supporters never apply it in turn to, say, major new government programs and regulations and economic interventions, despite many historically justified concerns about the risks of these programs.

But neither of these is necessarily the biggest problem with the precautionary principle. The real problem is that it focuses on only one side of the equation -- it says that risks alone justify stopping any action or policy without any reference at all to benefits of that policy or opportunity costs of its avoidance. A way of restating the precautionary principle is, "when faced with risks and benefits of a certain proposal, look only at the risks."

Since the precautionary principle really hit the mainstream with the climate change debate, I will use that as an example. Contrary to media appellations of being a "denier," most science-based climate skeptics like myself accept that man is adding to greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere and that those gasses have an incremental warming effect on the planet. What we deny is the catastrophe -- we believe we have good evidence that catastrophic forecasts from computer models are exaggerating future warming, and greatly exaggerating resulting forecast climate changes. Whenever I am fairly successful making this argument, the inevitable rejoinder is "well, the precautionary principle says that if we have even a small percentage chance that burning fossil fuels will lead to a climate disaster, then we have to limit their use immediately".

The problem with this statement is that it assumes there is no harm or risk to reducing fossil fuel use. But fossil fuel use pays enormous benefits to everyone in the world. Even if we could find near substitutes that don't create CO2 emissions (and it is every much open to debate if such substitutes currently exist), these substitutes tend to be much more expensive and much more infrastructure-intensive than are fossil fuels. The negative impact to the economy would be substantial. One could argue that one particular impact -- climate or economy -- outweighs the other, but it is outright fraud to refuse to discuss the trade-off altogether. Particularly since catastrophic climate change may only be a low-percentage risk while economic dislocation from reduction in fossil fuel use is a near certainty.

My sense is that if the United States chose to cut way back on fossil fuel use in a concerted effort, we could manage it and survive the costs. But that is because we are a uniquely rich nation. I am not sure anyone in this country understands how rich. I am not talking just about Warren Buffet. Even the poorest countries have a few rich people at the top. I am talking about everybody. Our poorest 20% would actually be among the richest quintile in many nations of the world. A worldwide effort to eliminate fossil fuel use or to substantially raise its costs or to force shifts to higher cost, less easily-used alternatives would simply devastate many developing nations, which need every erg their limited resources can get their hands on. We are at a unique moment in history when more than a billion people are in the process of emerging from poverty around the world, progress that would be stopped in its tracks by a concerted effort to limit CO2 output. Why doesn't the precautionary principle apply to actions that affect their lives?

College kids have developed a popular rejoinder they use in arguments that states "check your privilege." I thought at first it was an interesting phrase. I used it in arguments a few times about third world "sweat shops". I argued that those who wanted to close down the Nike factory paying $1 an hour in China needed to check their privilege -- they had no idea what alternatives those Chinese who took the Nike jobs were facing. Yes, you middle class Americans would never take that job, but what if your alternative was 12 hours a day in a rice paddy somewhere that barely brought in enough food for your family to subsist? Only later, I learned that "check your privilege" didn't mean what I thought it meant, and in fact in actual academic use it instead means "shut up, white guy." In a way, though, this use is consistent with how the precautionary principle is often used -- in many of my arguments, "precautionary principle" is another way of saying "stop talking about the costs and trade-offs of what I am proposing."

Perhaps the best example of the damage that can be wrought by a combination of Western middle class privilege and the precautionary principle is the case of golden rice. According to the World Health Organization between 250,000 to 500,000 children become blind every year due to vitamin A deficiency, half of whom die within a year of becoming blind. Millions of other people suffer from various debilitating conditions due to the lack of this essential nutrient. Golden Rice is a genetically modified form of rice that, unlike conventional rice, contains beta-Carotene in the rice kernel, which is converted to vitamin A in humans.

By 2002, Golden Rice was technically ready to go. Animal testing had found no health risks. Syngenta, which had figured out how to insert the Vitamin A–producing gene from carrots into rice, had handed all financial interests over to a non-profit organization, so there would be no resistance to the life-saving technology from GMO opponents who resist genetic modification because big biotech companies profit from it. Except for the regulatory approval process, Golden Rice was ready to start saving millions of lives and preventing tens of millions of cases of blindness in people around the world who suffer from Vitamin A deficiency.

Seems like a great idea. Too bad its going nowhere, due to fierce opposition on the Left (particularly from Greenpeace) to hypothetical dangers from GMO's

It’s still not in use anywhere, however, because of the opposition to GM technology. Now two agricultural economists, one from the Technical University of Munich, the other from the University of California, Berkeley, have quantified the price of that opposition, in human health, and the numbers are truly frightening.

Their study, published in the journalEnvironment and Development Economics, estimates that the delayed application of Golden Rice in India alone has cost 1,424,000 life years since 2002. That odd sounding metric – not just lives but ‘life years’ – accounts not only for those who died, but also for the blindness and other health disabilities that Vitamin A deficiency causes. The majority of those who went blind or died because they did not have access to Golden Rice were children.

Note this is exactly the sort of risk tradeoff the precautionary principle is meant to ignore. The real situation is that a vague risk of unspecified and unproven problems with GMO's (which are typically driven more by a distrust on the Left of the for-profit corporations that produce GMO's rather than any good science) should be balanced with absolute certainty of people dying and going blind. But the Greenpeace folks will just shout that because of the "precautionary principle", only the vague unproven risks should be considered and thus golden rice should be banned.

Risk and Post-Modernism

A few weeks ago, I wrote about Naomi Oreskes and the post-modern approach to science, where facts and proof take a back-seat to political narratives and the feelings and intuition of various social groups. I hadn't really thought much about this post-modernist approach in the context of risk assessment, but I was struck by this comment by David Ropeik, who blogs for Scientific American.

The whole GMO issue is really just one example of a far more profound threat to your health and mine. The perception of risk is inescapably subjective, a matter of not just the facts, but how we feel about those facts. As pioneering risk perception psychologist Paul Slovic has said, “risk is a feeling.†So societal arguments over risk issues like Golden Rice and GMOs, or guns or climate change or vaccines, are not mostly about the evidence, though we wield the facts as our weapons. They are mostly about how we feel, and our values, and which group’s values win, not what will objectively do the most people the most good. That’s a dumb and dangerous way to make public risk management decisions.

Mr. Ropeik actually disagrees with me on the risk/harm tradeoffs of climate change (he obviously thinks the harms outweigh the costs of prevention -- I will give him the benefit of the doubt that he has actually thought about both sides of the equation). Fine. I would be thrilled for once to have a discussion with someone about climate change when we are really talking about costs and benefits on both sides of the equation (action and inaction). Unfortunately that is all too rare.

Postscript: To the extent the average person remembers Bjorn Lomborg at all, they could be excused for assuming he is some crazed right-wing climate denier, given how he was treated in the media. In fact, Lomborg is very much a global warming believer. He takes funding from Right-ish organizations now, but that is only because he has been disavowed by the Left, which was his original home.

What he did was write a book in which he looked at a number of environmental problems -- both their risks and costs as well as their potential mitigation costs -- and he ranked them on bang for the buck: Where can we get the most environmental benefit and help the most people for the least investment. The book talked about what he thought were the very real dangers of climate change, but it turned out climate change was way down this ranked list in terms of benefits vs. costs of solutions.

This is a point I have made before. Why are we spending so much time, for example, harping on China to reduce CO2 when their air is poisonous? We know how to have a modern technological economy and still have air without soot. It is more uncertain if we can have a modern technological economy, yet, without CO2 production. Lomborg thought about just this sort of thing, and made the kind of policy risk-reward tradeoffs based on scientific analysis that we would hope our policy makers were pursuing. It was exactly the kind of analysis that Ropeik was advocating for above.

Lomborg must have expected that his work would be embraced by the environmental Left. After all, it was scientific, it achnowleged the existence of a number of environmental issues that needed to be solved, and it advocated for a strong government-backed effort led by smart technocrats doing rational prioritizations. But Lomborg was absolutely demonized by just about everyone in the environmental community and on the Left in general. He was universally trashed. He was called a climate denier when in fact he was no such thing -- he just pointed out that man-made climate change was way harder to solve than other equally harmful environmental issues. Didn't he get the memo that the narrative was that global warming was the #1 environmental threat? How dare he suggest a re-prioritization!

Lomborg's prioritization may well have been wrong, but no one was actually sitting down to make that case. He was simply demonized from day one for getting the "wrong" answer, defined as the answer not fitting the preferred narrative. We are a long, long way from any reasonable ability to assess and act on risks.

I think the author is being too optimistic about the outcomes if America significantly reduced its carbon emissions. Everyone understates just how much fossil fuels undergird modern life as we know it. Alex Epstein does a great job explaining the degree to which our standard of living depends on cheap energy in his latest book, The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels.

Have you listened to the recent Econtalk with Nassim Taleb? http://www.econtalk.org/archives/2015/01/post.html

Your post sounds like an attempt to dismiss what he says without actually mentioning it, and he does spend time specifying what he means by the precautionary principle.

He didn't get into it much, but one of the problem with GMOs is that golden rice is the oddball, not the norm. Crops are usually genetically modified as part of an arms race with nature, so that more pesticides and herbicides can be laden onto the fields without the crops dying. Consumers are at risk for more of these chemicals in their foods, and nature is at risk- while NPK is trucked into the fields. Much needed life in the soil is killed. Meanwhile, the offending weeds/bugs/etc- eventually respond, much like various human disease have to antibiotics by becoming resistant.

I think not allowing life to be patented, and honesty on labels would be enough. Outright bans are probably unnecessary.

So, I am anti-gmo, and people would shellac my with the anti-vax label because I am picky about which ones I would take and/or give to my children. I do not think atmospheric CO2 correlates particularly well with global warming, but there are other issues (like desertification) which exist and can be classified as climate change. Thankfully there are various private sector initiatives that will take care of many of these problems. The real problem is keeping the government out of the way.

But I think the same thing, even where we disagree- the problem is that people do not understand risk management. I am currently reading up on probability because I want to be sure I am assessing risk correctly. I started to notice this in a rather painful manner- that people were using their beliefs (religion) to create the illusion of certainty.

The last part there reminded me of the difference in funding by disease vs. actual cost (death) of a disease. I can't recall if you had a blog on this or not Coyote, and this certainly wasn't the graphic I had seen before... http://www.iflscience.com/health-and-medicine/infographic-shows-differences-between-diseases-we-donate-and-diseases-kill-us

But I was just about thrown out of a room for suggesting a shift away from breast cancer donations to other more harmful (more afflicting) diseases. I guess I was part of this war on women for saying that.

God, I wish statisticians had picked a term other than "confidence interval", because know-nothings keep pointing to it and say "ah ha, there's a 95% chance this is true!" And that's NOT WHAT IT MEANS.

" Had we followed such a principle consistently, we would still all be subsistence farmers, vassals to our feudal lord."

Actually, it's worse than you think. Had we consistently followed the precautionary principle from the very beginning, we would be stuck in the pre-fire stone age. Yes, that's right, following the precautionary principle we would never have discovered the single most important tool for the advancement of civilization, fire.

Half-ditto what Powers said, you've severely oversimplified what the 95% CI means (to be fair so did Munroe). What it really means is more like: If my sample was truly random, and I assumed the correct population distribution function, and I perform lots of samples, then 95% of the calculated CI intervals will contain the true (full population) value. So while the qualitative point that some significant number of studies report what is actually a false positive, it isn't correct to say that 5% of all studies are wrong. We don't actually know what the true rate of false positives is.

For example, physicists and sociologists might both use 95% CI for all their measured variables, but they will have wildly different cutoffs on correlation coefficients before claiming that two variables are actually correlated.

After all this you still have to worry about things like did I choose a good null hypothesis, are there confounding variables we didn't even measure, did one of my co-authors straight-up falsify some of the data? To paraphrase one of the great philosophers of our time, "there are known unknowns, and unknown unknowns." Confidence intervals are used to quantify one of the "known unknowns" in experimental setups, but they don't capture all of the unknowns.

So would it be more proper to say "a 95% confidence interval means that 95% of the studies actually found a meaningful result rather than a random occurrence".

No, confidence intervals refer to individual measurements (or subsequent calculations with that measurement), not the study as a whole. Now that I think about it some more though, Russell might have actually meant a p-test instead of a confidence interval (which also confusingly reference a 'confidence level'). If you calculate a p-value with a 95% confidence level (which is not the same thing as a 95% confidence interval) then you could think of this as being a 95% chance your study proved your hypothesis.

However, the more correct way of thinking about it is that there is a 95% chance that the null hypothesis was rejected for some reason other than random sampling error (ie 5% chance of a type I error caused by sampling, assuming the null hypothesis is correct). The 'other reason' could be that your tested hypothesis is correct, but it could also be that you had a poor null hypothesis, or a biased measurement, or fraud, etc, and it says nothing about type II errors. My main point is that the only thing a statistical test can tell you is how big of a problem random sampling error might be with a given sample size. They don't shed any light on all of the other ways an experimental setup might be flawed, so it is impossible for us to ever determine what percentage of studies result in flawed results.

If we apply the precautionary principle properly, shouldn't the formulation actually be "As someone who wants to change public policy, the burden of proof is on climate change advocates to show that their policy proposals have no risks"?

Alternatively ask if the debator in question can prove that their continued breathing has no risks, and since they can't, perhaps they should smother themselves.

That's why they also include the words "in the absence of scientific consensus", as an escape clause to give themselves permission to do this particular action.

Another problem with risk is that some people are absolutely freaky about risk without having any idea what their risk is. They may be terrified of germs without understanding that they are going to get a cold or two every year no matter what they do. They are terrified of radiation but put in granite counter tops which emit radiation. They eat the best food in the world and think they are being poisoned.

The counter to the precautionary principle is the delay in getting anything done. Keystone pipeline is classic. We have thousands of miles of pipeline, which most people simply don't know about, and putting all that oil on trains and trucks is much more dangerous than in a pipe. There is already a small town in Canada that burned up after a crash (2 yrs ago?). It is absurd that because a pipe goes across the border the feds have to get involved.

If we applied property rights properly, we wouldn't have to be arguing over the precautionary principle. You get to do what you want on your land, but you would be liable for screwing up other people's property, so, you take precautions to not screw up your neighbors land. A functional court system would be all that's needed. Practically every case, whether real or overblown- like Fukushima, for instance- involves government allowing one party to ignore it's liabilities to its neighbors. Smaller, safer nuclear designs have been around for a long time, but what is in production? 1970s behemoths run by folks with many lobbyists.

And here's some stuff on measles. Like I said before, the problem is poor risk management, it is just that I think you are the one displaying poor risk management skills: http://voxday.blogspot.com/2015/02/measles-actual-risks.html

1. Poor Understanding of ... Studies that Evaluate Risk

"Let's say in a year that the world does 1000 studies to test (correlations) that don't actually exist. Just from natural variation, 5% of these studies will still seem to show a link at the 95% confidence level. We will have 50 studies that year broadcasting false links. The media will proceed to scare the crap out of you over these 50 things."

Another big point here is "findings bias" in academic research. If you don't find a link your paper is generally considered quite uninteresting. Imagine going to a book publisher and saying "will you publish my novel in which nothing happens". Out of the 50 papers that identify a false correlation, you would get say 25* published. We would be lucky to get 5* of the 950 papers that accurately found no correlation published.

*No idea of publishing rates in science, but in Economics these number come close enough to truthiness.

To address your first point some more, I think it is an understatement to say people are bad at evaluating incremental risk. It appears most lay people are fundamentally incapable of thinking of risk as a probability at all, and treat all evaluations as if they were binary. So anything they've accepted or at least deal with on a regular basis are deemed 'safe' and anything unusual (or even common but not obviously apparent, like GMOs) is potentially 'dangerous'. With this mindset, evaluating incremental or comparative risk isn't just difficult, it is nonsensical. In the same way that adding a bunch of 0s will never get you to 1, combining a bunch of 'safe' things would never add up to a 'dangerous' state of affairs. With the bathtub/terrorism example I doubt anyone would even care about the bathtub drowning rates, their thought process would just be "I take a bath everyday without incident, therefore it is safe, full stop."

Well said, Coyote. Like usual.

I guess what we're asking here is "how the hell do we describe a statistical result in a way that's meaningful to the layman", and we're hoping that the answer is not a Sheldon Cooper tantrum about imprecision in language.

Finally something written by someone who's at least trying to be rational. It seems that way too many people just want to establish membership in some elite intelligencia by labeling themselves "rational" purely based on supporting whatever they think is commonly labeled the "rational" belief among that elitist social group. (Be suspicious any time someone says "the rational thing to believe is" or "the educated thing to believe is".)

I'd argue that social cognition is the main challenge to rational thinking. Anyone who tries to question anything that's a de facto religious belief of the group they find themselves in is going to find themselves labeled an evil heretic. For example, in de facto religious terms, "denier" is really just a synonym for "heretic" or "infidel" because from the social cognitive perspective it's being used in the same way and has the same effect. This is because a significant number of people just want to claim "rationality" as a moral credential for moral licensing purposes and so pointing out the lack of rational basis for a belief is like Martin Luther pointing out the pope's lack of holiness.

Human brains really haven't changed significantly in at least the last 50,000 years, if not longer, so it isn't surprising that people can't avoid "religious thinking". This is worsened by the fact that people use semantic arguments to try to deny being guilty of religious cognition by claiming that a belief is only religious (and therefore irrational) if it relates to a god somehow, after which they claim not to believe in a god. Therefore they must automatically be purely rational!

Unfortunately it seems that many people treat "science" as though it's some sort of "science god" and "scientists" like some sort of priests or prophets. This is the natural consequence of not understanding what science is, and social cognition taking over. Then, to make things worse, they don't know who the fraudulent or erroneous "science priests" actually are because this judgement is made based on social cognition rather than complete knowledge of what's going on.

To Coyote:

Bravo

}}} how do I prove there are no invisible aliens in my closet who may come out and eat me someday

Clearly this is easy, having already been proven true by that wonderful documentary film, Monsters, Inc....

:-9